80 Years of Pain: Ukraine calls for recognition of 1944 Crimean Tatar genocide on 80th anniversary

On May 8, 2024, Ukraine’s Parliament addressed foreign governments and parliaments on the 80th anniversary of the Crimean Tatar genocide in 1944, issuing a series of calls.

ZMINA explains how the deportation of Crimean Tatars took place, what the Ukrainian parliament is calling for, and why it is important.

The Verkhovna Rada called on foreign governments and parliaments, international organisations, and parliamentary assemblies to recognise the 1944 deportation of the Crimean Tatars from Crimea as an act of genocide against the Crimean Tatar people and to join in commemorating its victims on 18 May.

Furthermore, the Verkhovna Rada called on them:

- to condemn the criminal actions of the USSR‘s totalitarian regime aimed at orchestrating genocide in 1944;

- to recognise the Russian Federation’s large-scale, unprovoked armed aggression against Ukraine as a continuation of Russia’s genocidal imperial policy, which aims to colonise Ukraine and enslave the Ukrainian people;

- to demand that the RF, as a member state of the United Nations and a permanent member of the UN Security Council that is systematically failing to fulfil its duties, should abolish the unlawful restrictions on the right of the Crimean Tatar people to conserve their representative institutions; in particular, to implement the judgment of the UN International Court of Justice that the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people should resume its work;

- to take an active part in the implementation of the Peace Formula of President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy, known as the Ukrainian Peace Formula, including where it pertains to the release by the Russian Federation of all persons deprived of their freedom as a result of armed aggression against Ukraine, including representatives of the indigenous Crimean Tatar people, and the complete de-occupation of the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine in order to achieve a comprehensive, just and sustainable peace in Ukraine and the security of the whole world.

In total, 317 MPs voted in favour of Resolution №11237.

Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev in the Verkhovna Rada on May 8, 2024

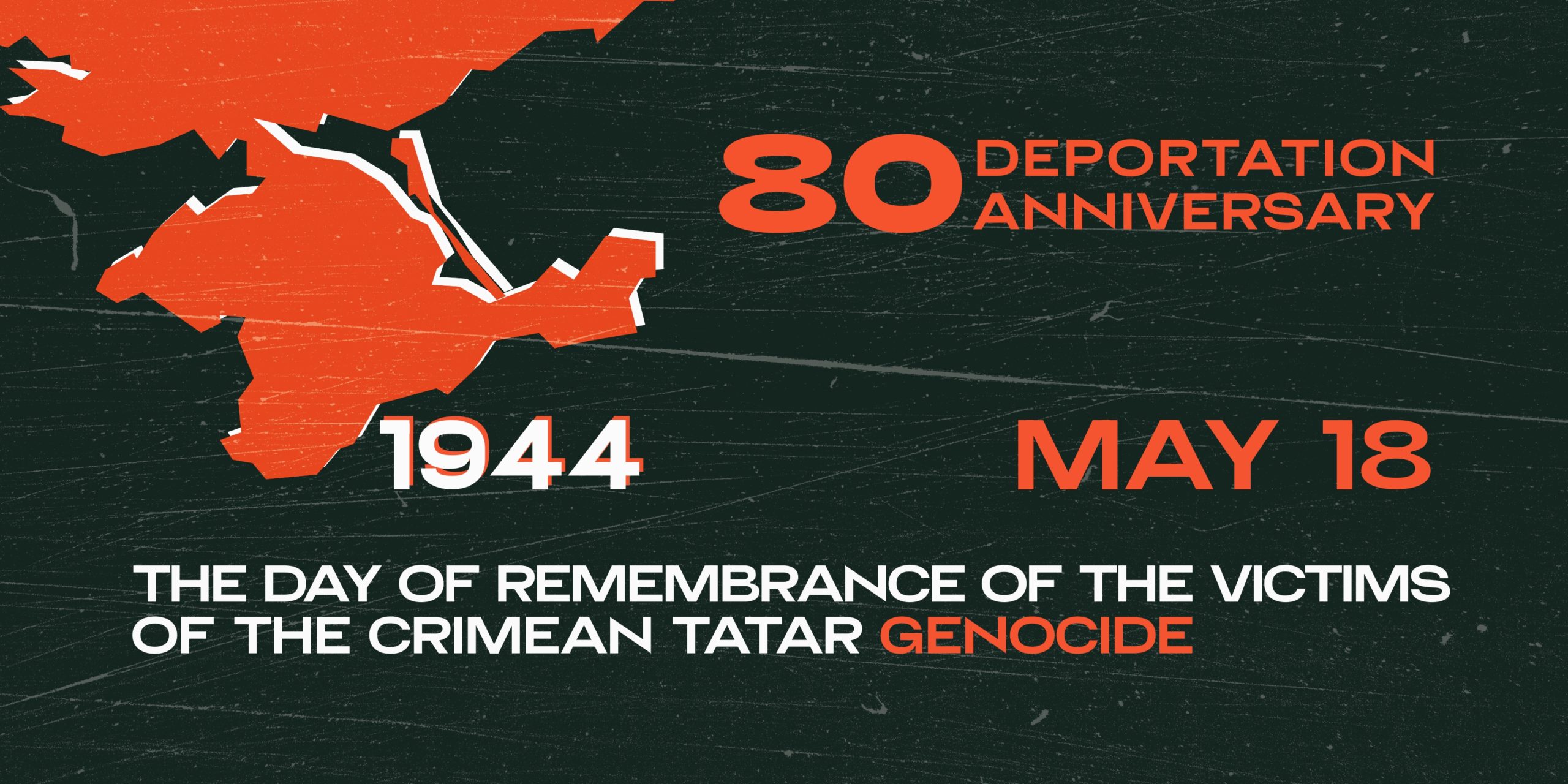

Crimean Tatar leader Mustafa Dzhemilev in the Verkhovna Rada on May 8, 2024Annually, on May 18, a Day of Remembrance of the Victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide is commemorated in Ukraine. In 2024, the 80th anniversary of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people from the Crimean Peninsula by the totalitarian Soviet regime will be marked.

How did the Soviet regime commit genocide against the Crimean Tatar people?

At dawn on May 18, and in some settlements the day before, on May 17, the USSR orchestrated the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars, predominantly targeting children, women, and the elderly, while men were in the fighting services at the frontlines of World War II. This was part of a Russian colonial policy aimed at de-Tatarization of Crimea.

The Decree of the State Defense Committee of May 11, 1944, personally signed by Joseph Stalin, completed the process of forced displacement of the indigenous people from their land, which began immediately after the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783.

Eyewitnesses say the operation carried out by the involved personnel was brutal. In most cases, an explanation was never given to the Crimean Tatars for what was happening and where they were being taken, and they were given no more than 15 minutes to pack. Thus, the Crimean Tatars left their homes unprepared for a long and exhausting journey, not to mention settlement in a foreign land.

According to the Decree, the deportation was to be completed by June 1, 1944, but the repressive Soviet regime once again used repression to “exceed the plan.”

The Soviet regime carried out the deportation using 23,000 NKVD soldiers and officersі 9,000 NKVD and People’s Commissariat for State Security operatives, 100 cars, 250 trucks, and 67 trains.

Already at 8 a.m. on May 18, 1944, an estimated 90,000 Crimean Tatars were boarded in 25 trains consisting of freight cars. Roughly 48,400 Crimean Tatars in 17 trains had already been deported to Uzbekistan. On May 19, 165,515 Crimean Tatars were deported in freight cars. Eventually, such a high pace allowed the Soviets to report to Moscow on May 20 about the “cleansing” of Crimea from Crimean Tatars.

Inside the genocide: suffering and loss

The murderous journey of the deportees in freight cars to the “places of special settlement” lasted an average of 2–3 weeks. On the way, in cramped boxcars, without food, water, or medical care, 7,000–7,900 Crimean Tatars died of starvation and disease.

After the end of World War II, a total of almost 9,000 Crimean Tatar soldiers and officers of the Soviet army were sent to places of deportation or labour camps. During World War II, 21 Crimean Tatars were nominated for the Hero of the Soviet Union award. For instance, the two time Hero of the Soviet Union was awarded to an exemplary pilot, Amet Khan Sultan (August 1943, June 1945). Five Crimean Tatars were bestowed with the title Hero of the Soviet Union.

According to the Department of Special Settlements of the NKVD, in November 1944, 193,865 Crimean Tatars were in exile: 151,136 of them in Uzbekistan, 8,597 in the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, and 4,286 in the Kazakh SSR. The rest were distributed “for use in labor” to Molotov, now Perm (10,555), Kemerovo (6,743), Gorky (5,095), Sverdlovsk (3,594), Ivanovo (2,800), and Yaroslavl (1,059) regions of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

This number does not include almost 6,000 Crimean Tatars imprisoned in Gulags directly during the deportation. Deported representatives of the indigenous people were granted the status of “special migrants”. This involved constant surveillance by repressive Soviet structures, registration in commandants’ offices, and forced physical labour at exhausting jobs.

According to the NKVD of the Uzbek SSR, 16,052 Crimean Tatars (10.6%) died of disease and inhumane conditions during the first six months of deportation, and 13,183 (9.8%) in 1945. In Uzbekistan alone, almost 30,000 Crimean Tatars died during the first year and a half of deportation.

In 1948, the regime of exile in special settlements became even more repressive. In particular, individuals who left the special settlements were subjected to arrest for five days. Furthermore, repeated violations of the “regime of residence” were recognized as an “escape from the place of exile,” which resulted in imprisonment for 20 years.

Historians remark the genocide was also exemplified by the Soviet regime’s actions to erase the memory of the Crimean Tatars from the history of the Crimean Peninsula: Crimean history was revised, Russian imperial narratives about the “eternally Russian” Crimea were introduced, and myths about the “traitorous people” were deliberately and massively spread. Immigrants from the RSFSR and the Ukrainian SSR were brought to Crimea and deliberately settled in the homes of Crimean Tatars.

The repressive Soviet regime ultimately changed and distorted Crimean place names, in particular, replacing the names of settlements and streets of Crimean Tatar origin with Russian ones. The Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea highlights that the totalitarian Soviet regime’s policy against the Crimean Tatars was a de facto continuation of the Russian Empire’s tradition of colonising the Crimean Peninsula. This tradition began with the annexation of Crimea in the eighteenth century, when the Crimean Tatars were evicted and their rights and freedoms were restricted.

Cultural erasure and colonisation during the rule of the Russian Empire

Before the 1783 annexation of the Crimean Khanate by Russia, the Crimean Tatars constituted over 92% of the population. 157,319 people lived in Crimea in 1795, including 126,000 Crimean Tatars. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Russian Empire pursued a policy of constant pressure on Crimean Tatars, restricting their rights and religious freedoms, burning religious books, and taking away land and resources. A significant part of the indigenous people was forced to leave Crimea.

The indigenous population of Crimea was replaced by colonists. Finally, on June 25, 1946, the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR adopted a law that approved the transformation of the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic into the Crimea region.

The tragic story of the deportation of the Crimean Tatar people was suppressed in the USSR for decades. The language and culture of the indigenous people of Ukraine were banned. Crimean Tatars were not only deprived of their homeland but also of their name, language, history, and identity.

After Stalin’s death, the Crimean Tatars’ rights were not restored and they were not allowed to return to their homeland. Their exile continued.

Despite the ban, starting in 1967, Crimean Tatars made numerous attempts to settle on their land in Crimea. The Crimean Tatar national movement for return was one of the most influential and vivid protest movements in the USSR. But the real mass return, repatriation, began after 1987.

Ukraine has taken the step of declaring the crime of forced deportation to be an act of genocide against the Crimean Tatar people, guided by the provisions of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. As the Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea explained, this was committed in response to the Russian totalitarian regime’s policy of oppression of the indigenous people of Ukraine.

Modern quiet deportation

For decades, the communist regime of the USSR and later Russia deliberately had been spreading the myth of “betrayal” against Crimean Tatars. Today, the occupying country uses this narrative to spread hate speech, discrimination, and hostility in occupied Crimea; according to numerous Crimean human rights defenders. Russia denies the genocide of Crimean Tatars in 1944 and does not take responsibility for Stalin’s repressions and deportation.

Russia’s policy of ongoing oppression is expressed through deliberate violations of the rights of the indigenous people of Ukraine, illegal conscription, destruction of cultural heritage, falsification of history, and militarization of education and public life.

Russia’s Federal Security Service conducted mass searches in the temporarily occupied Crimea in about seven homes on On March 11, 2020. At least five Crimean Tatars were detained in the city of Bakhchisaray and the Bakhchisarai district and transferred to the FSB building in Simferopol that day.

Russia’s Federal Security Service conducted mass searches in the temporarily occupied Crimea in about seven homes on On March 11, 2020. At least five Crimean Tatars were detained in the city of Bakhchisaray and the Bakhchisarai district and transferred to the FSB building in Simferopol that day.Persecuted Crimean Tatars, including numerous political prisoners in Russian captivity, have claimed that since the 2014 occupation of Crimea, Russia has been deliberately repressing the Crimean Tatar people, continuing the crimes of the totalitarian Soviet regime and the Russian Empire.

In April 2023, Dunja Mijatović, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, released a report, “Crimean Tatars’ struggle for human rights.” Mijatović confirmed numerous serious human rights violations, namely persecution, discrimination, and stigmatization, by Russian occupying forces of representatives of the Crimean Tatar community and those who oppose the illegal occupation of Crimea.

In recent years, the Seimas of Latvia and the Seimas of Lithuania, as well as the House of Commons of Canada, have recognised the deportation as a genocide of the Crimean Tatar people.