You sit like a potted plant: you may be watered, or you may not, and then you will wither – journalist Dmytro Khyliuk. A story of captivity and freedom

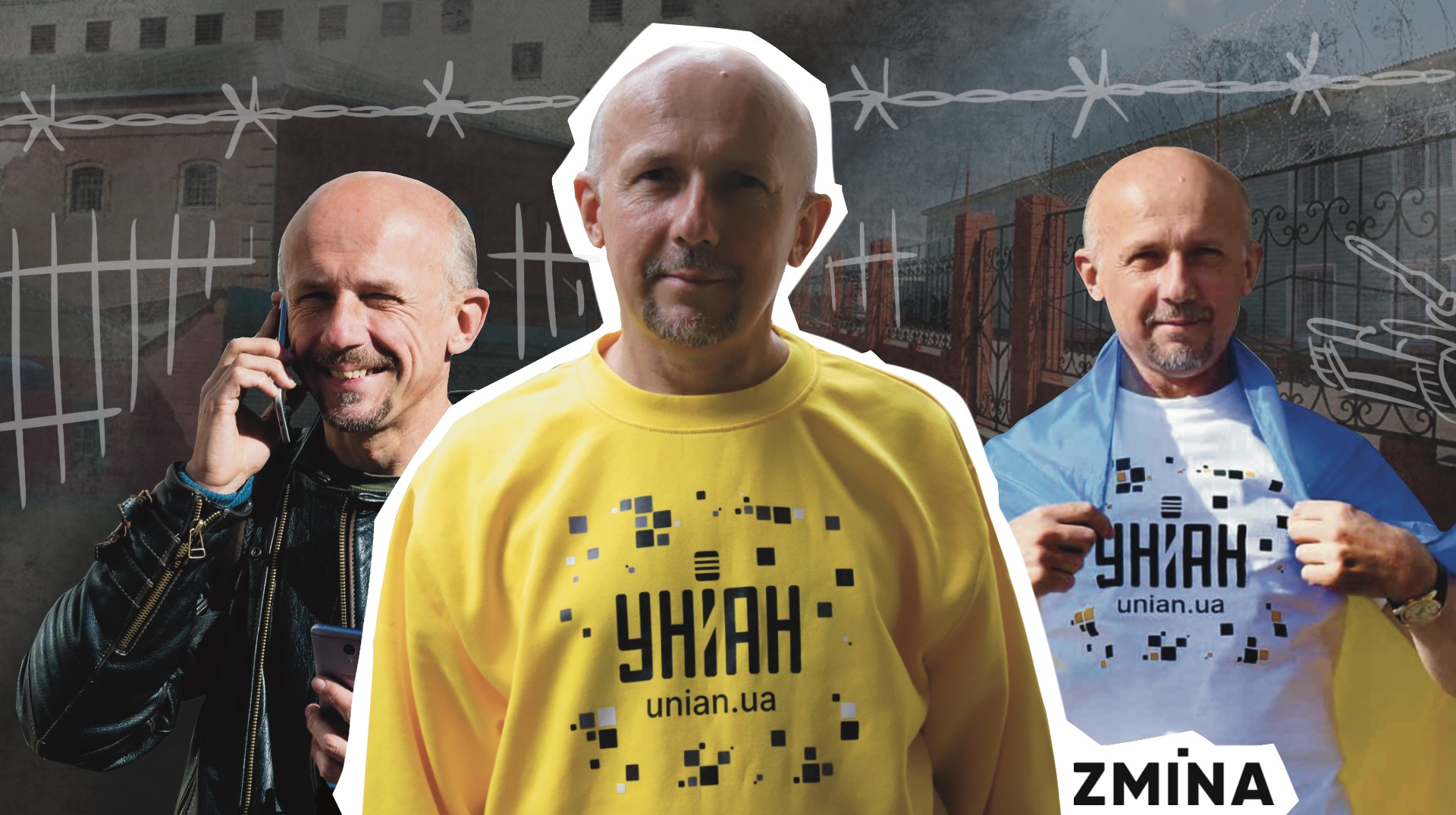

Ukrainian journalist of the UNIAN news agency Dmytro Khyliuk returned home on 24 August 2025 after three and a half years of Russian captivity. He was abducted in the Kyiv region in March 2022, along with his father, when the occupiers took over the village of Kozarovychi. His father was released after eight days, while Dmytro was sent to a number of prisons and camps. He was unlawfully detained for a long time without access to a lawyer or any official information from the Russian authorities

President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy announced the journalist’s release and thanked the Ukrainian team and international partners, in particular the UAE, for their assistance in organising the exchange. Immediately after his return, Dmytro congratulated Ukrainians on Independence Day and expressed his gratitude for their support, admitting that he was impressed by the attention and care shown by the people.

His abduction is being investigated by the Prosecutor General’s Office as a war crime, and Dmytro and his father are considered victims. The journalist emphasises that he was never a prisoner of war, but only a civilian captive.

A journalist from ZMINA, Oleksandra Yefymenko, met with Dmytro Khyliuk at the hospital where he is currently undergoing treatment and rehabilitation. She spoke with him about the first days of the occupation of the Kyiv region, the conditions of detention for Ukrainians in Russian colonies, what helped him maintain his psychological resilience in captivity, and what he plans to do in the future.

How did the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine begin for you?

On 24 February, I heard but hadn’t yet seen the full-scale invasion. At about five in the morning, there were loud explosions in the sky, distant but very powerful, shaking the windows. It was clear that there would be no more sleep. I realised that war had begun. At about seven, I started getting ready for work. I thought, ‘What should I do?’ I have to go to work. I turned out to be a bit foolish because, even though I understood that war was going on, I went anyway.

On the way, I saw a huge number of cars driving towards me, leaving Kyiv – as it turned out later, heading into the danger zone.

There were long queues at the petrol stations. When I arrived at the UNIAN office, most people were already working remotely, but the building was open. The centre of Kyiv was absolutely deserted. Only one television crew was walking around. In the evening, on my way home, no one was moving along the highway in either direction. The petrol stations were closed, there was no petrol, and the lights in the villages were off.

The next morning, I heard the rumble of military vehicles. I got on my bike and rode over – a convoy was heading towards Kyiv, marked with the letters “V” or “Z”. I realised: it was the occupiers. By lunchtime, some of them had already turned towards our village and were driving past my windows towards the Kyiv Reservoir. They set up camp there. That’s how the occupation began for me.

Dmytro Khyliuk. Photo credit: Oleksandra Yefymenko

Dmytro Khyliuk. Photo credit: Oleksandra Yefymenko“They were looking for “saboteurs” and looting”. About the occupation of his home and captivity

When did Russian soldiers first come to your house in Kozarovychi?

They came on March 1 [2022]. My father and I were taken outside. My mother stayed in the house, as she could hardly walk after a stroke. They broke the gate with a crowbar and entered the yard with their guns at the ready. We locked the door, but they started pounding on it. I realised they would break it down, so I opened it. They forced us out into the yard. Inside, one of them literally stood over my mother – “so that she would not kill them”, although she was over 70. When they left, I saw that the clock and the flashlight were missing. Then I realised that this was their usual round. They were looking for “saboteurs” and looting. They stole my parents’ phones, even the push-button ones. They didn’t find mine because I hid them.

Two days later, on March 3, you were imprisoned together with your father. How did that happen?

The day before, a shell had hit our yard and blown out the door. My mum was taken to stay with a neighbour for the night, while my dad and I stayed behind. On the morning of the 3rd, we went to that neighbour’s house because she had gas and our pipe had been broken. We decided to bring some groats for lunch. I was walking ahead because my dog was running around the yard, and he was supposed to be in the house. I saw the occupiers, who were already holding their weapons at the ready near my father. I approached them, and they put me on the ground and searched me. That’s how my captivity began.

They took us to a warehouse in Kozarovychi, where household appliances used to be stored. It was a dark room with no windows. When they brought me in, there were already several people with their hands tied. They added new ones. They were fellow villagers, as well as those who were passing through our village on their way to Kyiv. Russian soldiers kept us there from March 3 to 6.

They released my father and several other elderly people. They said, “Go”. Their hands were untied, and they were led out. He walked with the others, afraid that they might shoot him in the back. They didn’t let him go home – the occupiers were already living in the house. He spent the night in a garage, then made his way to a neighbour’s house, where my mother was staying.

Kyiv region, after deoccupation in 2022, Vyshhorod district. Photo credit: Oleksandra Yefymenko

Kyiv region, after deoccupation in 2022, Vyshhorod district. Photo credit: Oleksandra YefymenkoCan you recall the entire route – how and when you were taken from Kozarovychi and when you ended up on the territory of the Russian Federation?

On March 6, we were transported to the rural settlement of Dymer, to a factory, where we remained until March 10. Then we were taken to the settlement Hostomel, and on the 17th to Belarus, to the Gomel region, to the town of Narowlya. We stayed in Belarus for about a day and a half. Then, on March 18, we were sent to Pre-trial Detention Centre No. 2 in the city of Novozybkov, in the Bryansk region, 170 kilometres from the Ukrainian border.

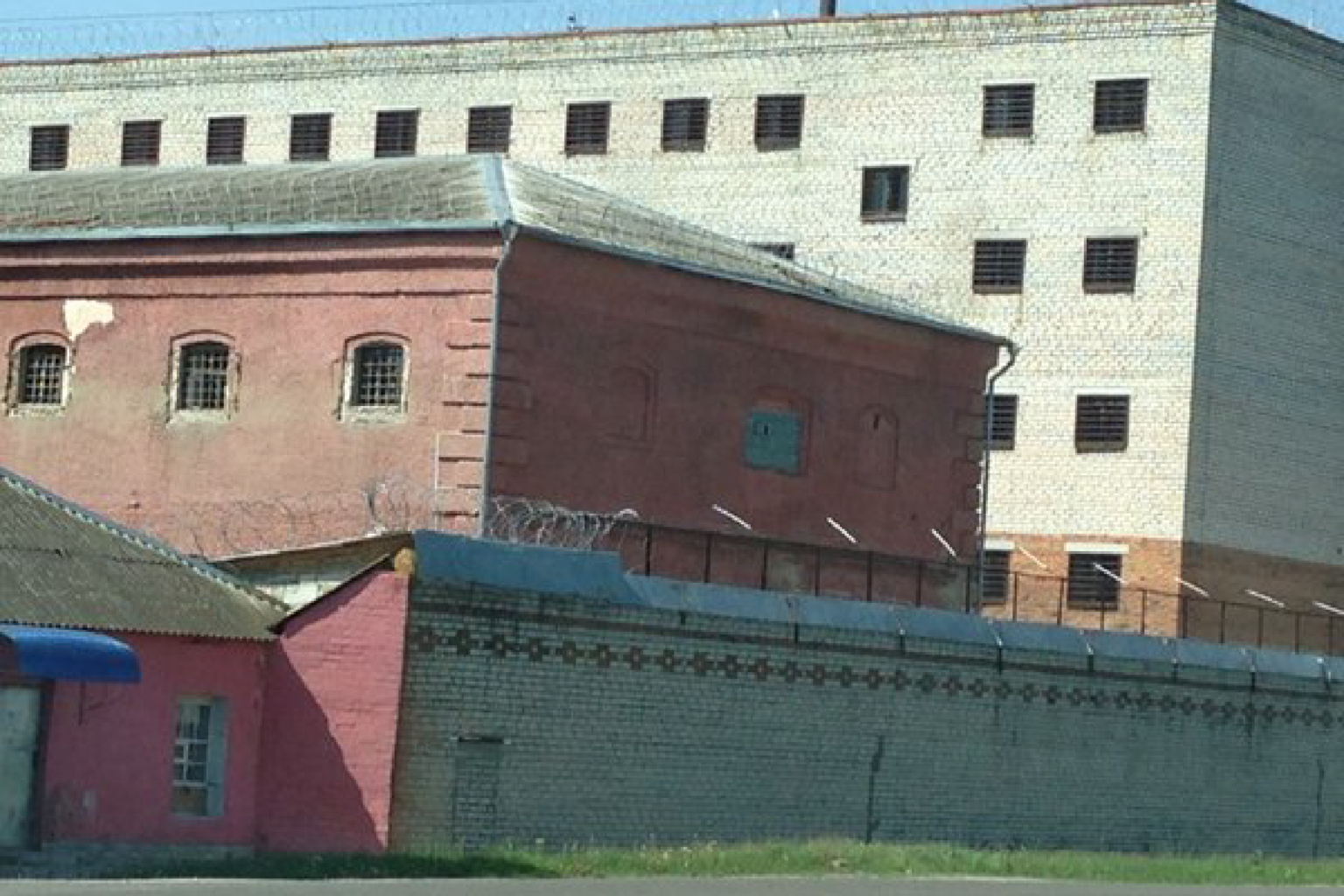

Bryansk Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2, Novozybkov. Photo credit: MIHR

Bryansk Pre-Trial Detention Centre No. 2, Novozybkov. Photo credit: MIHRPlease describe the facility and the length of your detention there.

Pre-trial Detention Center No. 2 is an old pre-revolutionary prison, a dilapidated building. We were held there for more than a year, from March 18, 2022, to May 2023. At first, the three of us were held in a new building. Then I was moved to a solitary cell – 33 days alone. Later, a guy from Irpin was placed with me, and we spent almost a year together. The cell was five by two meters. It was very cold and damp, even when it was +30 outside.

I remember that the so-called intake procedure was very harsh. They beat everyone with sticks and their feet. A dog bit me in the side. Everything was dark before my eyes, because they were blindfolded. They threw me to the ground and beat me on the head. I later learned that there had been an order to break the “khokhols”і as much as possible – through hunger and beatings. They carried this out with sadistic pleasure.

After May 2023, where were you transferred to next?

To the penal colony in the urban-type settlement of Pakinoі , Vladimir region. This was no longer a pre-trial detention centre but a large colony. There were also Russian inmates there. The cells were overcrowded: 15 people where there should have been six. They installed bunk beds, and the passageways were narrow.

When the Red Cross came, one bed was removed, and some of the people were moved out. There were only Ukrainians in my cell. There were three buildings in the colony, where there were also only Ukrainians. We were additionally surrounded by a six-metre-high fence and closely monitored to ensure that we did not communicate with local prisoners. We had our own separate area inside. We heard that it was a large prison because every morning during the check, the locals shouted “Zdravstvuyte!”і . And we heard a lot of those “Zdravstvuyte!”. When they were all lined up, we could hear it dozens of times. We were only a small part of that colony.

“At first we were forced to watch Russian news, but in September 2022 the televisions were suddenly removed”. About life in Russian captivity

Could you describe your daily routine in the Pakino colony?

It was the same every day, like Groundhog Day. Wake-up was at six in the morning, followed by exercises. After that, they brought the so-called food. Then came inspection – we had to go out into the corridor wearing only underwear and vests, facing the wall. One of them would call out surnames, and you had to answer with your first name, patronymic, and year of birth.

At the same time, they would look into the cell to check that there was nothing “extra” there. Afterwards, they asked if there were any health complaints. If there were, a medical orderly chosen from among us had to report them. Each cell had one person responsible for mentioning who was ill: who had a fever, who had a skin rash. Their response was very sluggish. If someone had a high temperature, then yes. But if it was a toothache or a headache, nobody paid any attention.

Colony in the urban-type settlement of Pakino. Photo from open sources

Colony in the urban-type settlement of Pakino. Photo from open sourcesIn one of your interviews, you said that all the colony employees hid their faces.

Yes, all of them. Even the inmates who served us. Everyone wore balaclavas or covered their faces in some way. This was already in 2023. They were afraid of being identified.

Was it the same in Novozybkov?

It was a bit easier there. Those who just did their jobs and did not beat us did not cover their faces. Two of them even spoke to me. One of them joked, when I was going to the shower: “So, Khyliuk, will you write about me when you get out?”.

And what about Pakino?

In Pakino, everyone hid completely. They were afraid of retribution. There, they all used pseudonyms, and we never knew their surnames. For example, that old “doctor” who mocked the prisoners instead of treating them – a real scum. And the senior operative who summoned me for an “interview” without a protocol. When he was alone, he spoke more or less normally. But when colleagues were around, the swearing and showboating began.

Am I correct in understanding that no “case” was ever opened against you?

No cases were initiated against us. All civilians were given the status of “a person counteracting the Special Military Operationі “. I learned this from a representative of Ombudswoman Moskalkova. It was a label to justify keeping Ukrainian civilians there. No specific charges were brought.

You spent three years in information isolation. How did you find out what was happening in Ukraine?

Only through rumours. Someone who had been with a new arrival would pass on something they had heard, and it spread further. But everything was distorted, like a “broken telephone.” For instance, whether we controlled cities such as Perekop or Enerhodar, no one really knew. In Novozybkov, they still brought in televisions and forced us to watch Russian news. But around September 2022, they suddenly removed all the TV sets. That was when I realised something had gone wrong for them. Later, it turned out that this was when the de-occupation of the Kharkiv region began, along with mobilisation in Russia.

And after your return, how did you catch up on three years of information vacuum?

Gradually, in small doses. I spoke with colleagues. I suspected that the war had entered a protracted phase. But I was shocked by how advanced the drones had become – that they were striking cities hundreds of kilometres from the front line.

“I recalled school math formulas”. On psychological resilience and release on Independence Day

How did you cope psychologically in captivity? What helped you?

I tried not to think about bad things. That must have been a defence mechanism. Sometimes thoughts would overwhelm me: the war is in the village, what if the house has been destroyed, my parents killed, and I am stuck here for another ten years, and what then? I pushed such thoughts away. I tried to think about something detached. For example, I recalled school math formulas. There was nothing to check them against. You would sit there for three hours just trying to recall the formula for the area of a circle. Or you ask the others: “Do you remember how to calculate that?“.

Conversations helped a lot. Books, too, although most of them were Soviet and Russian, not always of high quality, but they still helped. The main thing was to keep yourself under control. I understood that banging my head against the wall would not help. And there was no one to appeal to. It was very frustrating and depressing that nothing depended on you. You sit there like a potted plant: they may water you, or they may not, and you will wither. Complete passivity.

Could you please tell me about the day of the exchange? Was it clear in advance that you were being prepared for release?

We expected exchanges on every holiday. Ours – Independence Day, Christmas, Easter. Theirs – Russia Day, May 9. On those days, there was always hope. On August 20, the lads heard my surname being called out in the corridor. Everyone said, “They’re taking you today!” I was glad, but I still did not fully believe it. Indeed, after lunch, an inmate who collaborated with the administration came and took me with my belongings. We knew that he was always the one who took people away for exchanges.

We were moved to the “dispatch” cell. I was there with the former mayor of Kherson, Volodymyr Mykolaienko, another young man with mental health issues, and an elderly man with a heart condition. Then we were given Ukrainian military uniforms – old ones, taken from our prisoners of war. We realised it was about an exchange. We had to record a video on camera: “I have no complaints against the Russian Federation, the conditions of detention were normal, meals were provided three times a day”. Then we wrote a short autobiography. But in the evening we were returned to the ordinary cells again. The lads were shocked. Yet they reassured me: “Once they’ve pulled you out, you’ll definitely be leaving soon”. And indeed, on the morning of August 23, I was taken out again with my belongings. This time for good.

What was the exchange process itself like?

We were taken into a prison van with our eyes and hands tied. Then we were transported to an airfield. There we were put on a military transport aircraft. You could tell by the smell of kerosene and the benches along the sides. We flew for about two hours and landed in Belarus, in Homel. There, our blindfolds were removed. I saw Belarusian licence plates on the buses and ambulances. I realised that the colony was over. After that, it was Ukraine. We boarded our buses and went home. Along the road, people greeted us with flags and flares. It was very touching.

How are your parents now? What about the house?

My parents are ill; they are already elderly. My mother broke her leg this summer after a stroke. My father developed cancer from all the stress. The house was damaged by a Grad strike. It is difficult, but I am glad they lived to see my return.

I read that you have already given your first interview since your release to Kostiantyn Davydenko. When do you plan to return to work full-time, and do you plan to do so?

I do plan to, of course. I think sometime in mid-October to November, after treatment. The war has changed everything; I will have to adapt to a new format. It will not be as it was. During the war I had worked for less than a week, five or six days.

Language support: ZMINA volunteer Lisa DeHaven