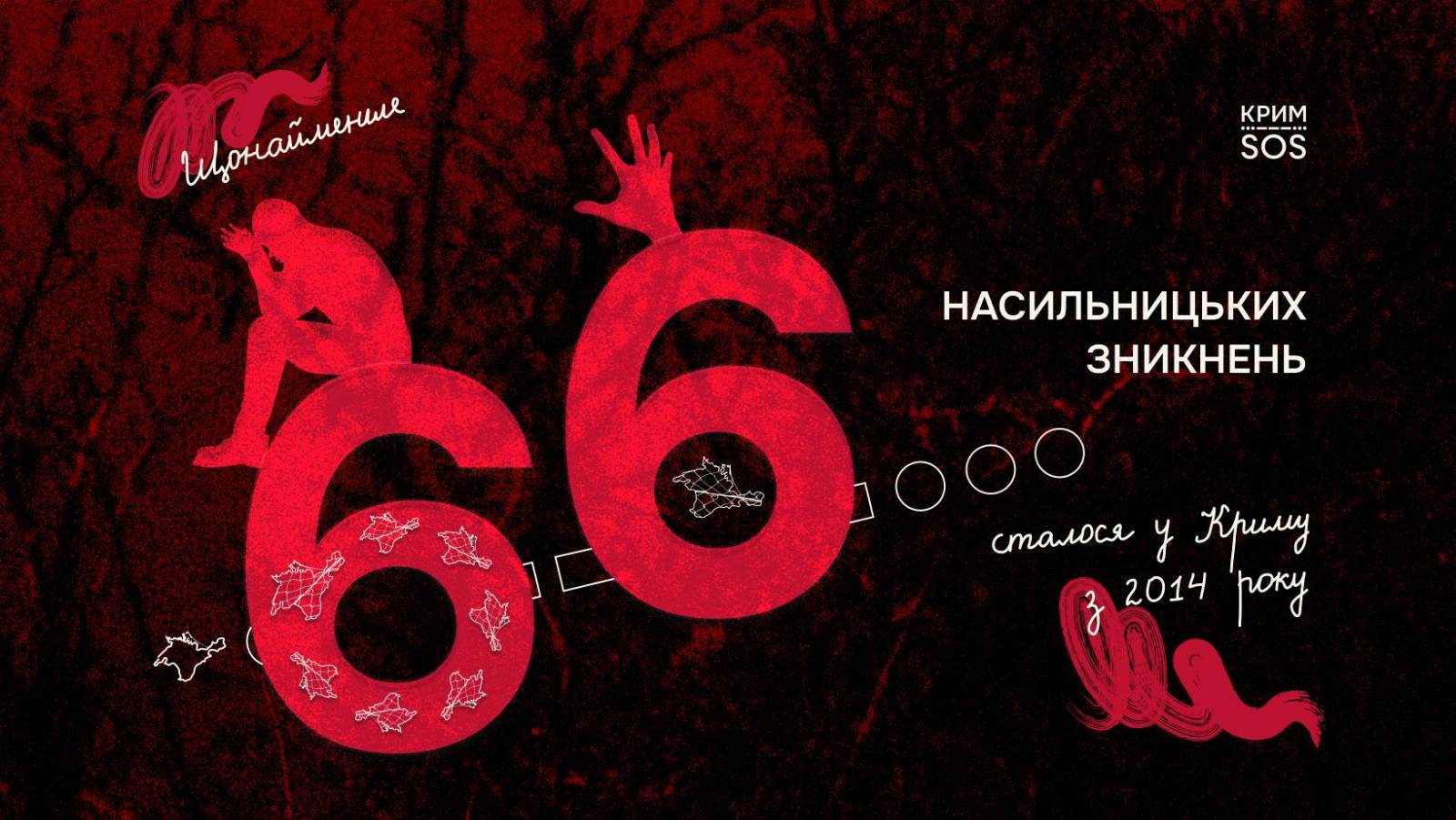

Crimea SOS reports 66 cases of enforced disappearances in Crimea since Russia’s attempt of annexation

The human rights organization Crimea SOS has recorded at least 66 cases of enforced disappearances in the temporarily occupied Crimea since the onset of the Russian occupation of the peninsula.

“The fate of 21 of these individuals remains unknown, six have been found dead, one person was extradited abroad, seven were charged with crimes, and 31 people were released within a few days,” said Yevhen Yaroshenko, an analyst at Crimea SOS.

He identified four waves of enforced disappearances on the occupied peninsula. According to Yaroshenko, the first wave occurred during the establishment of Russian rule in Crimea and in March 2014.

“During this period, at least 25 pro-Ukrainian activists became victims of enforced disappearances. In particular, Reshat Ametov, who held a solo picket in Simferopol, was found dead 12 days later with signs of tortures. In addition, members of the pro-Russian paramilitary ‘Crimean self-defense’ held the leaders of the Ukrainian community of Crimea, Andriy Shchekun and Anatoliy Kovalskyy, in arbitrary detention for 11 days, and the fate and whereabouts of five pro-Ukrainian activists, including Valeriy Vashchuk, Ivan Bondarenko, Vasyl Chernykh, Timur Shaymardanov, and Seyran Ziniedinov, are still unknown,” the human rights advocate said.

The second wave of enforced disappearances occurred in the fall of 2014. The victims were mainly Crimean Tatars, including the son and nephew of human rights activist and veteran of the Crimean Tatar national movement Abdureshit Dzhepparov, whose fate and whereabouts have been unknown for over ten years.

The third wave lasted from August 2015 to May 2016 and also affected the Crimean Tatar population more. For example, since May 24, 2016, nothing has been known about the fate of the kidnapped well-known activist of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people, Ervin Ibrahimov.

The fourth wave began with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Russian troops began mass abductions of people in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions, dozens of whom were subsequently placed in pre-trial detention facilities in Crimea, including Iryna Horobtsova, Oleksiy Kyselyov, Ruslan Abdurakhmanov, and Rustem Osmanov.

“During this period, Russian security forces returned to the widespread practice of abducting people at the entrance to Crimea and directly on the peninsula. In particular, according to available information, the fate of six people remains unknown, most of whom were detained by Russian security forces after searches. There were cases when people were released a few hours after arbitrary detention or after serving administrative arrest on dubious charges. Some were formally charged after prolonged arbitrary detention. Many also became victims of enforced disappearances due to their open or alleged pro-Ukrainian views,” Yaroshenko added.

The latest victim of enforced disappearances, according to Yaroshenko, was the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Tatar children’s magazine “Armanchyq,” Ediye Muslimova, who was abducted on November 21, 2024. When the situation became public, the woman was released.

The human rights community in Ukraine also believes that the de-occupation of Crimea is necessary to stop the systematic violations of human rights committed by the Russian Federation on the peninsula. They are urging other countries to support Ukraine with timely and sufficient weapons and military equipment supplies towards this end.

Earlier, the human rights NGO Crimea SOS emphasised that ignoring the war crimes of the Russian occupiers has led to a deterioration of the human rights situation in the occupied Crimea. The lack of response from the international community to the occupation of Crimea and the further crimes of the occupiers made it easier for Russia to turn the peninsula into a springboard for the invasion of mainland Ukraine in 2022.

In July 2023, Wayne Jordash, the managing partner of Global Rights Compliance LLP, said that the International Criminal Court is not doing enough to investigate international crimes against civilians in the temporarily occupied Crimea.