“The father did not find out where Raim was before his death”: why Russia transfers Crimean political prisoners as far as possible from their relatives

At the end of June 2024, the Crimean political prisoner Raim Aivazov, who was illegally sentenced by a Russian court to 17 years of imprisonment in a high-security prison, was transferred from Ulyanovsk to the Arkhangelsk region of the Russian Federation – to penal colony No. 21. However, the family of the Crimean Tatar knew about it only on July 30. And a few days before that, Raim’s father died – 56-year-old Khalil Aivazov, who, unfortunately, did not hear from his son for a long time.

The systematic practice of transferring Crimean political prisoners to unusual climatic conditions and as far as possible from their families has been used by the Russians since the beginning of the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula. The occupying administration of Crimea needs to suppress internal resistance to the occupiers, and they try to break the most dangerous citizens for the authorities in any way.

Separation from relatives, the inability to see them, to feel the support of loved ones, infrequent letters and rare phone conversations through the prison connection “Zonatelecom” are the result of the suffering of entire families. The psychological state of families cannot fail to have a direct effect on political prisoners as well.

Human rights defenders consider this as one of the methods of Russian pressure on those who disagree with the occupation policy in Crimea, which is being implemented contrary to all norms of international law.

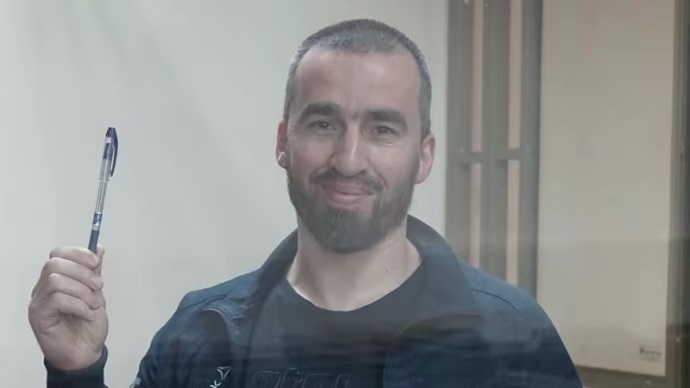

Raim Aivazov. Photo: Crimean Solidarity

Raim Aivazov. Photo: Crimean SolidarityRaim Aivazov: Transferred much further away from his relatives

Raim Aivazov’s wife Mavile told ZMINA that during his transfer, her husband managed to make short phone calls from time to time and inform about his location. He was taken through Ulyanovsk, Kazan, Perm, Yaroslavl… Until the last, no one said where exactly he would be sent to serve his sentence.

Only after a week without communication, Raim contacted his relatives and informed them that he had reached the final place where he would serve his remaining term – this is penal colony No. 21, located in the Plesetsky district, Iksa village of the Arkhangelsk region of Russia.

When Raim was just transferred to prison, Mavile immediately wrote a request asking that her husband be transferred to serve his term closer to home. The answer traditionally was negative. On the contrary, he was staged even further away from his family. If earlier there were about two thousand kilometres between them, now it is three thousand.

“Unfortunately, when his father died, Raim was in the process of being transferred, and to this day it is difficult for him to accept the fact that his father is no longer alive,” said the political prisoner’s wife.

Crimean Tatar activist Raim Aivazov was illegally sentenced by the occupiers to 17 years in prison as part of a fabricated criminal case about his involvement in “terrorism”.

His father Khalil Aivazov last saw his son in 2021 – during a court hearing in Rostov-on-Don. The father had hoped to meet him on a long-term date after another transfer of Raim to another Russian colony, but this did not happen.

As of July 2024, the Russians transferred five Kremlin prisoners to various penitentiary institutions on the territory of the Russian Federation. They were sent to the Arkhangelsk region, Chuvashia, the Republic of Mari El. All these places are thousands and thousands of kilometres away from their homeland – Crimea. Therefore, Crimean political prisoners have very little chance of meeting their relatives in the coming years.

Moreover, the place of induction of one of them – Remzi Bekirov, is still unknown.

Remzi Bekirov: there is no communication with the political prisoner

The wife of Crimean political prisoner Remzi Bekirov Khalide said that her husband spent a year in the city of Yeniseysk, Krasnoyarskyi Krai, which is 5,500 kilometres from Crimea. Now he has been transferred to an unknown place: neither the family nor even the political prisoner is informed of the destination.

“I wrote a statement asking for clarification, but the first response I received from the administration of the prison where the husband was kept was that “such information is not disclosed to third parties.” I even attached to the statement marriage certificate, but you see – they consider me as a third person,” the woman said.

Remzi Bekirov. Photo: Crimean Solidarity

Remzi Bekirov. Photo: Crimean SolidarityAt the same time, Khalide sent a statement to the Federal Penitentiary Service of the Russian Federation. The answer came in just three weeks: Remzi is in Krasnoyarsk pre-trial detention centre No. 1. This is a temporary distribution point, where exactly he will be sent later – unknown.

During the entire time that Remzi Bekirov was in custody, he did not have a single meeting with his family. They could see each other only at court hearings in Rostov-on-Don.

“The defendants are kept in such glass boxes, which are called here ‘aquariums’. And we are in the courtroom as listeners. That’s the only way we saw each other through the glass, we were not allowed to communicate”, shares her memories Khalide.

Since he was kept under strict conditions in the Yeniseisky colony, he could call his family only once a year. Towards the end of his imprisonment, he managed through the court to have it changed to a general regime. After that, he had the right to have three calls per month.

“But according to the administration, the prison allegedly does not have enough staff to accompany him to the phone, so he called home once a month, and that was already in the last months, before the transfer”, said the political prisoner’s wife.

In general, he and his family were in some confusion for a long time after the verdict was announced. Because it was written so vaguely that even the lawyers were surprised how many different ways it could be understood, Khalide says.

It was not clear whether the years served in the pre-trial detention centre would count towards the five-year prison term he was sentenced to, or not. That is, after a year in prison, he should be transferred to a colony, or he would have to spend all five years there.

That time Remzi also managed to get clarification through the court: the four years he spent in the pretrial detention centre is included in the general term of five years in prison. The last year ended in June 2024, and the Crimean Tatar was transferred in July. Khalide tried to get Remzi transferred closer to home.

“While he was in prison, I wrote a statement to the Federal Service for the Execution of Penalties three or four times with the demand to transfer him closer. But each time I received different answers”, the woman said.

At first, she received an answer that he could not be transferred to Crimea, because “there are no colonies for particularly dangerous criminals – terrorists” on the peninsula. In the next statement, she asked to transfer Remzi to the Krasnodar Territory or Rostov. The answer was that in these and several other regions of the Russian Federation, there is a regime of increased terrorist danger due to the war with Ukraine.

“In the next statement, I chose the area on the map that is not part of this regime – the Stavropol Krai. I sent it. I was wondering, what justification they would come up with this time. I received an answer that I could write this kind of request only after the husband has already been transferred to the colony. It’s absurd”, Khalide says.

Now she is waiting for the moment when Remzi will reach his final destination, then she will try again to get him transferred closer to home.

If her husband is placed thousands of kilometres from home, the meeting may not happen soon. During the year he spent in the Krasnoyarskyi Krai, Khalide was unable to visit him even one time. The woman underwent an operation in November last year, before the operation she had seizures. After the operation, for six months, she was forbidden to overexert herself and not to get hypothermia.

“And Remzi was in Siberia, such a long way with my health absolutely did not allow me to visit him. Now I have a postoperative period, an acute phase. If they will transfer him so far, I am not sure that my health will allow me to travel to him.” – doubts the woman.

Crimean political prisoner Arsen Abhairov, who was Bekirov’s cellmate in Krasnoyarsk and Yeniseysk, was transferred far away to Buryatia, she says.

“It’s actually 7,500 kilometres from Crimea. So, we don’t know what to expect now. Children are living a dream. To go, fly to Dad and see him”, Khalide says.

On March 10, 2022, the Russian court in Rostov-on-Don illegally sentenced Crimean citizen journalist Remzi Bekirov to 19 years in prison for “terrorism” and “preparation for a violent seizure of the Russian government.” He served the first five years of his sentence in prison, and the rest of the sentence is to be served in a penal colony.

Riza Omerov: “I see the sky and the sun, I am alive”

The wife of political prisoner Riza Omerov Sevile said that in July of this year, her husband was transferred from Minusynsk through Kazan to the colony of the city of Tsyvilsk in the Chuvash Republic of the Russian Federation. The family did not hear from him for six months – from December 2023.

Riza Omerov. Photo: Crimea Solidarity

Riza Omerov. Photo: Crimea SolidarityImmediately after his arrival, the Crimean Tatar was placed in a quarantine zone, and he was allowed to call his relatives. The call lasted one and a half minutes, and that’s when he explained where he was.

“But the first thing he said was: ‘I see the sky and the sun'”, says Seville. Because during the five years behind bars, he was limited not only in communicating with people, but also almost did not see sunlight. He had such a voice when he talked about the sky… I don’t even know how to describe his state at that moment”.

But now he is closer to Crimea than before, the woman smiles bitterly: it was five thousand kilometres away, and now it is one and a half thousand.

Relatives have not seen Riza for five years. The youngest son was born after the arrest, so he never saw his father at all – only in photos.

“Sometimes, a new babysitter comes to the kindergarten and asks the boy: “Who will take you home, mom or dad?” And he answers: I don’t have a dad at home, I have a grandfather, and my dad is in prison. And he begins to cry, saying: “But I love him very much, my mother shows me his photos”. Here the babysitters and teachers start crying with him. Can you imagine how stressful it is for a child?”, Sevile says.

Enver and Riza Omerov

Enver and Riza OmerovThe eldest son of the Omer family began to have serious psychological problems after his father’s arrest. He screamed at night and was extremely afraid of everything related to the police, military equipment, and even ambulance sirens.

The family had to work with private psychologists to bring the boy out of this condition because the state doctors offered only one way out – to have him committed to a psychiatric hospital.

Additionally, after the arrest of his father, he developed a heart complication. He had a congenital defect from his childhood and was registered with a cardiologist. Before the occupation, there was a time when doctors said that it was possible to be removed from the register because everything had settled down. But after Riza’s detention, Sevile noticed that the child’s nasolabial triangle was turning blue again, and he began to lose weight – that is when the problem returned.

“We were told that the child should avoid stress. But how can we do that when stress is around us all the time? The question of when the father will come, I cannot answer. Whether his father will be released alive from prison, I cannot answer either”, Sevile says.

Children miss their father very much.

“I try to give them everything, but you can’t be both a father and a mother at the same time. It is very easy for someone to destroy a family in a few hours, to impose 15, 20 years of imprisonment on false charges. And the consequences for children are very destructive”.

The woman says that she would like to take the children to meet their father, even though it is very far.

“I want him to meet the children because I don’t know what might happen to me in a second. Or what might happen to him, there’s absolutely no guarantee of safety, and no one is responsible for the lives of our husbands in prison,” – Sevile said.

The woman hopes that the opportunity to see Riza will be soon. Although such a long trip and meeting in a place of detention will also be stressful for children, she is convinced.

“I want to take them to their father, but I’m afraid of it. So that it does not affect the psychological and physical state of our son, who has heart problems. Or that the younger one will suffer the stress of being separated from his father after they meet.”

Seville once again emphasizes: her husband, like other Crimean political prisoners, is not a criminal, rapist, murderer, did not commit or prepare any terrorist attacks, did not sell drugs…

He is an ordinary civilian, an ordinary Muslim.

But it turned out that it is very easy to come up with a criminal article for any person if someone else just wants it.

“It is terrible when political prisoners find out about the death of their relatives and cannot attend the funeral because of their imprisonment. Raim Aivazov’s father died recently, he went to work and did not return. In February, Ayder Japparov’s son, 13-year-old Abdullah, died. He had cancer, which was diagnosed after his father’s arrest. Riza’s grandmother died without knowing about the place of imprisonment of her grandson and son Enver until her death. It shouldn’t be like that”, says the Crimean Tatar woman.

She still hopes for an exchange so that all political prisoners return home.

“But I’m afraid to tell anyone about it, especially children, lest It can break their little hearts if it doesn’t happen. I just pray to God that justice prevails soon and everyone goes home.”

The woman often imagines what her husband’s return home will be like.

“I told him, when you come back, I will wear a white dress and marry you again. And he laughs and asks: “And in which car will we go?”. “I don’t care where and how, even to any part of the world, but the main thing is to be next to you,” – smiles Sevile.

And in a second she sighs: “You know, on the outside, I’m steel armour, but inside I’m a tired warrior, you know? But we’ll pass all the difficulties because we’re a family.”

Crimean Tatars – father and son Enver and Riza Omerov were sentenced by the Russian occupiers to 18 and 13 years of imprisonment in strict regime colonies on charges of “terrorism” on a religious basis.

Enver Omerov was transferred from Vladimir Central Prison; he is still in this process. It is known that they planned to transfer him to serve his sentence to the city of Yoshkar-Ola in the Mari El Republic of Russia at the beginning of August this year.

Vladlen Abdulkadyrov and Ayder Japparov: difficult transferring

On July 11, 2024, political prisoner Vladlen Abdulkadyrov, a member of the “Second Simferopol Group” in the Hizb ut-Tahrir case, was transferred to the penal colony No. 21 of the Arkhangelsk region. The institution is located in the village of Iksa, Plesetskyi district of the Russian Federation.

Vladlen Abdulkadyrov. Photo: Crimean Solidarity

Vladlen Abdulkadyrov. Photo: Crimean SolidarityPreviously, he was inducted at the prison of the city of Yelets, Lipetsk region of the Russian Federation.

The wife of the Kremlin prisoner Gulzar, said that Vladlen called his family through the prison communication channel “Zonatelecom” and said that he had been traveling for more than 70 hours, and the entire transfer process was accompanied by eight searches of personal belongings.

Another Crimean political prisoner, mosque muezzin Ayder Japparov, was transferred from Verkhnyuralsk prison in the Chelyabinsk region to the penal colony No. 5 in Koryazhma in the Arkhangelsk region in early July of this year.

Ayder Japparov

Ayder JapparovAccording to the Russian court verdict, he had to spend three years in prison. Ayder’s wife noted that in June 2022, the head of the Verkhnyuralsk prison didn’t want to accept a political prisoner, because he had already served three years in a pre-trial detention centre and was to be immediately transferred to a colony. However, they did it only two years later.

Russian security forces detained Ayder Japparov in June 2019 in the case of the so-called Hizb ut-Tahrir group from Biloghirsky district. Later, he was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

In February 2024, Ayder’s son Abdullah died of cancer. The father could not even bury his son and say goodbye to him.

Ayder Japparov was tried by the Russian occupiers together with his son and father Omerov in the “terrorism” case. On January 12, 2020, the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don sentenced him to 17 years in prison.

The occupiers are purposefully transferring political prisoners to the Russia to put pressure on dissenters – expert of ZMINA

“Analysing these cases, we see that the Russian Federation systematically transfers illegally detained Ukrainian citizens to Russian territory to further try and imprison them. In essence, the occupation authorities in Crimea are trying to legitimize their criminal actions by forced passportization of the population in occupied Crimea. International humanitarian law prohibits the occupying power from implementing its legislation in the occupied territories and judging people according to its laws. Forcible displacement and transferring of people are also prohibited”, – Viktoriya Nesterenko, project manager of ZMINA Human Rights Center, says.

Political prisoners and their relatives perceived such a policy of the Russian Federation as a crime by the Russian authorities with the intention of continuing the genocide of the Crimean Tatar people. They call it “silent deportation”. Since the occupying power in Crimea creates harsh life conditions for civilians who disagree with the repressive policies, those civilians are then forced to either leave the peninsula themselves due to the risk of persecution, or face repercussions and eventually be transferred to Russian colonies. As a result of the criminal actions of Russia, the majority of political prisoners are already in colonies and prisons within the territory of the Russian Federation, far from their homeland.

Among the Ukrainian citizens illegally convicted by Russia on fabricated charges are elderly individuals, individuals with disabilities and those who are seriously ill and – even according to Russian legislation – are not eligible to serve sentences in places of detention. Many such people are sentenced from 10 to 20 years in prison. All of these individuals are at risk of not surviving until the end of their imprisonment. It often happens that they are transferred to even worse conditions than before.

“Transferring of political prisoners complicates access to then their families and lawyers. That is why we constantly talk about all these violations by the Russian Federation on international platforms, stressing that it is necessary to make maximum efforts and advocate for the return of our people home”, said the human rights defender.