A typical day in a Russian prison (a diary of a civilian hostage)

Russia holds prisoners of war and civilians in an extensive network of prisons inside the country and the occupied territories of Ukraine.

The conditions of detention there typically do not meet even basic human rights standards: prisoners are systematically subjected to torture, beatings, and physical violence. They are not provided with proper medical care, are constantly interrogated, and are subjected to psychological pressure and humiliation. Russia deliberately uses Stalinist methods, creating camps everywhere for “enemies of the people, spies and terrorists.”

ZMINA has obtained a diary written by one of the Kremlin’s prisoners, Dmytro (name changed for security reasons), which he secretly kept throughout his imprisonment. We also spoke with Yevgen Yamkovyi and Viacheslav Zavalnyi, who learned firsthand what the modern Russian penitentiary system is like.

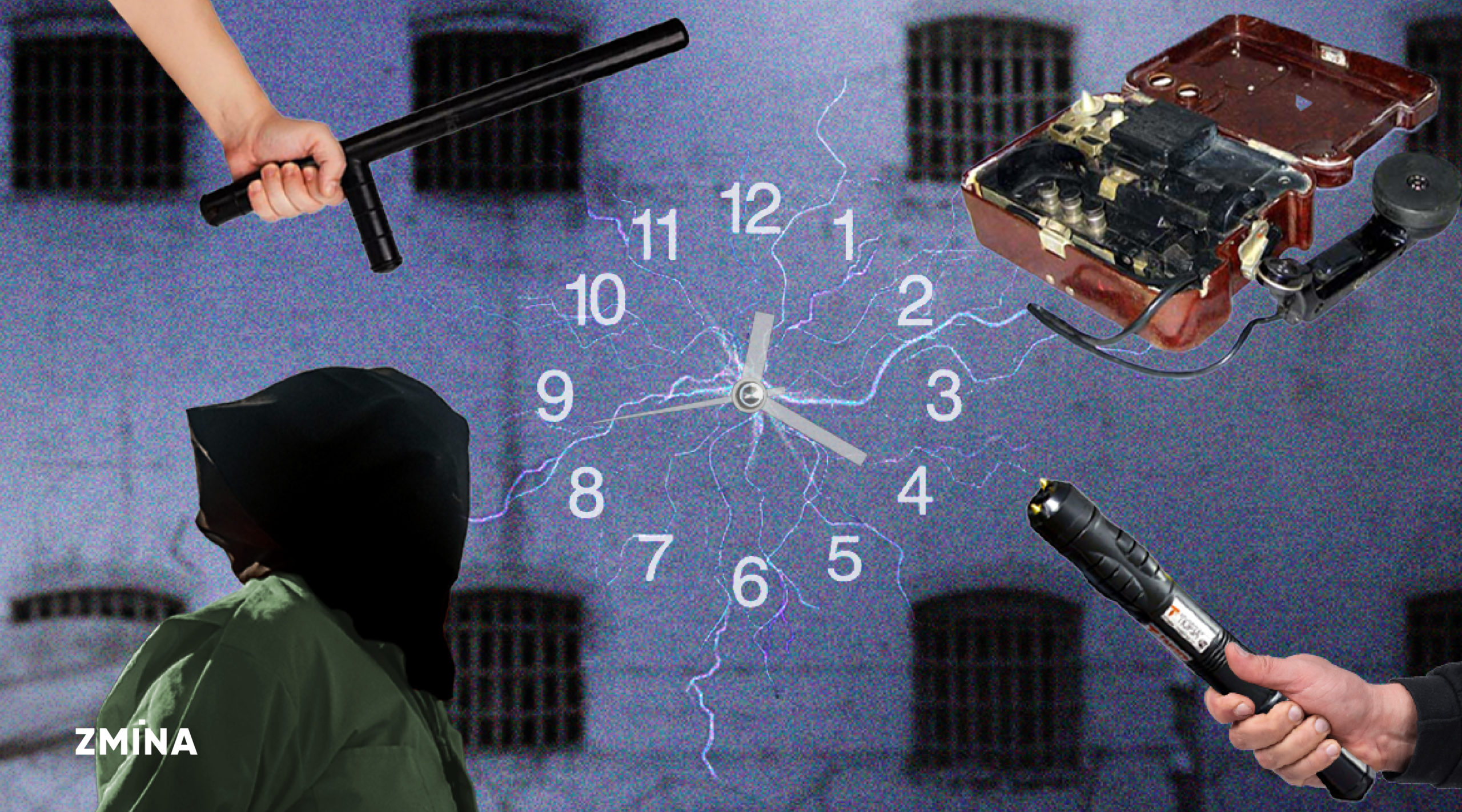

A collage created by ZMINA

A collage created by ZMINA“Admission” to the detention center, after which not everyone survives

Dmytro was first transported to the Rostov prison by airplane, where he slept on the floor with other civilians and then – was transferred to a prisoner vehicle. During this “trip,” detainees used bottles to go to the toilet. When prisoners were finally brought to the local pre-trial detention center, the guards brought them in one by one.

The so-called “reception” was already waiting for them there. This is a procedure where guards line up on both sides of the room, holding batons and stun guns.

All newly arrived prisoners are passed through this “corridor” while the detention facility’s staff kicks, punches, and pushes them.

“I was told that in other similar establishments, it is even worse. People are beaten and tortured so severely that some even die. It is considered the norm.” (Hereinafter, citations from Dmytro’s diary. – Ed.)

Then, Dmytro was taken to a room where he and the other prisoners were ordered to kneel, huddle tightly together, keep their hands behind them, and tilt their heads down. Everyone was asked who they were and why they were detained.

During the interrogation, Ukrainians were constantly called names. Also, according to the former prisoner, the Russians repeatedly told them,

“We have been giving you gas for 30 years. You should be grateful to the Russian soldier for saving your life.”

Those with casts on their limbs were separated from the main group of detainees. Some of them had their casts removed right there.

“We were divided into five groups and told to move at a 90-degree angle. Everyone had to move crouching with their hands behind their backs and their palms clasped together parallel to their shoulder blades. Even in this position, they could not look up.”

After that, Dmytro was ordered to remove his clothes and throw them on the floor. The guards beat him several times with a stun gun.

In the next room, he and the other prisoners were already waiting for two “hairdressers” – they did not cut their hair but pulled it out, the man recalls.

His ears were pulled back, and a clipper was shoved into his nostrils. At the end of the procedure, the “hairdresser” slapped Dmytro.

The whole process was accompanied by laughter from the detention facility’s staff.

Then, the men were taken to a bathhouse. They were given 1 to 2 minutes to wash without detergents.

“After that, you are given a prisoner’s uniform and underwear 3 to 5 sizes too big. Without exception, all prisoners were given boots of size 41, even if you were a size 45.”

Dmytro’s fingerprints were taken in the next room, and the guards filled out some documents. He was hit in the face again. In another room, the detention center staff in balaclavas was waiting for the man. They beat Dmytro on the kidneys and liver and tased him while laughing.

After all the “procedures” and registration, Dmytro was led by the hand to a cell with other Ukrainians. Other hostages told him about prison life, the schedule, and the daily routine.

The cell had two rooms: the first had beds, and the second had a toilet, a sink with cold water, and a table with two benches. According to the rules, the prisoners were forbidden to raise their arms above the benches, close their eyes, laugh, or even smile. They could only go to the toilet or the sink one at a time.

“There were video cameras in the cell, and operators watched the prisoners 24/7. If someone violated their rules, the operator would immediately complain to the special forces, who would run into the cell and beat everyone up.”

In addition, according to the former prisoner, the cameraman could report violations to the supervisor. The latter, for his part, made the prisoners squat 200 times.

The cells also had an intercom on the wall. Sometimes, the operator would call it, which meant a last warning for the prisoners.

Like other prisoners, Dmytro was given a roll of toilet paper, toothpaste, a brush, and a small bar of laundry soap. Sometimes, Russians gave one large bar of soap to two people.

It was also a shock for the man that the institution’s staff provided bedding with lice.

A day in jail: continuous torture

At 6 a.m., Dmytro would wake up, get dressed, and line up with the other prisoners. His head was bowed, his chin was pressed to his chest, and his hands were kept behind his back.

When the cell’s door or window was opened, the guards ordered everyone to sing the Russian anthem and shout, “Glory to Russia!” After the guards entered the cell, the cell officer on duty had to report,

“Citizen chief, there are *number* people in cell *number*. The cell officer on duty is *name*, *name* is absent”.

At 6:30, Dmytro, stripped to the waist, had to do half an hour of exercise.

Until 8 a.m., the pre-trial detention facility had a change of duty officers or cell searches conducted once a week.

After that, the prisoners had to go out into the corridor one by one, holding their hands behind their backs. They had to stand facing the wall with their feet shoulder-width apart. During the inspection, Dmytro was beaten on his torso, face, and genitals.

Sometimes, he was forced to kneel with his forehead touching the floor.

“It all depended on the mood of the guards. When checking the cell for prohibited items, they hit the bed and bars with a mallet. At the same time, other guards would beat prisoners with batons or a plaster stick. It was excruciating,” the man recalls.

After the search, breakfast was served, which Dmytro, sometimes a cellmate on duty, received for everyone. He was given eight bowls, spoons, cups, and bread through the “feeder.” When everyone had eaten, the cellmate on duty had to wash the dishes in cold water without detergent or sponges. He then had to give it all to the guard, and in return, he was given a needle and thread, a bowl for cleaning, etc. Dmytro had to shout loudly, “Thank you! Glory to Russia!” each time.

According to Dmytro, they were held on the first floor of a three-story barracks. Sick people were taken to the first-aid post on the second floor, and each time, they were forced to shout, “Glory to Russia!”

Over time, the prisoners were no longer taken there, and the doctor gave them all the pills they needed through the window of the “feeder.” The prison’s doctor usually went to the cells at 4 p.m. and mainly distributed medicines to those who complained of sick heart or blood pressure problems during registration.

“When someone in our cell fell ill with a high fever, they took him to the medical center. “The warden later told us: “He’s a drug addict. He died. Maksym is dead, and to hell with him.” None of us sought medical help anymore.”

To go to the bathhouse, Dmytro held the soap in his hands with two fingers behind his back. The man walked in a line, resting his head on the buttocks of the prisoner in front of him.

Upon entering the bathhouse, Dmytro undressed, knelt, and listened to instructions from the wardens,

“It should be quiet in the bathhouse, like in a library, even if you are beaten! If you scream, we will beat you harder! You can’t walk fast! Two people per tap! If you’re washing, you can’t look at the staff!”

“In the bathhouse, we would wash for 2 to 3 minutes – one would soap up, and the other would stand under the tap. We took turns washing off the soap. There were 8-10 wardens in the bathhouse who would come up to everyone, ask their name, and beat them with a truncheon, stun gun, foot, or hand.”

It was in the bathhouse that Dmytro was severely beaten and forced to take off his pants.

If Dmytro dropped the soap while moving from the cell to the bathhouse and back, forgot it in the shower, or put it in his pocket, he was immediately beaten. He had to have the soap in his hand at all times.

Usually, Dmytro was interrogated until 6 p.m., but sometimes he could be summoned in the evening. During these so-called “conversations,” he was tased, a bag was put over his head, and electric cords from a field phone were attached to his hands. It all depended on the team that was “working” with him.

“They also used needles to attach the phone to their little toes, ears, genitals, and calves. After being tortured with electricity, prisoners would urinate or vomit. It was different for everyone. I didn’t have any of that.”

From 5 p.m. to 6 p.m., Dmytro had dinner and exercised again. At 8 p.m., the second staff shift was in the detention center. At 9 p.m., he would start preparing for the “wake-up call” – brushing his teeth, washing his face, singing the Russian anthem, and shouting, “Good night, citizen warden!”

The guards would start counting to 10, and if the prisoner did not have time to go to bed, he would be taken out of the cell and beaten.

Once, Dmytro stood up for a prisoner being held by two burly guards and raped by a third. The man was severely beaten with sticks, kicks, and a taser.

Realizing that he would not survive, the Russians let Dmytro go home to die, but his family managed to save him. Now Dmytro has an iron plate in his head, he can barely speak, and his liver and kidneys are damaged.

Simferopol Detention Center #2: Special Forces and young wardens are the most brutal

Former Kremlin prisoner Yevhen Yamkovyi said he was woken up at six in the morning and given breakfast an hour later. After that, the guards would make a round of the territory, open the door, and listen to the report of the cell attendant. He would tell them: “Citizen inspector, let me report: cell 47, 4 people are present, cleaning is underway, all systems are in order. There are no complaints or claims.”

A photo of Yevhen Yamkovyi, provided by his family

A photo of Yevhen Yamkovyi, provided by his familyIf Yevhen needed to ask them for something, he would address the wardens as follows: “Citizen warden! Let me tell you my request.”

The man would list everything they were missing, such as toilet paper, thread, shaving machines, and soap. Before Yevhen was released, he had not seen toilet paper or soap for a month. Before that, he and his cellmates were given three bars of soap, one of which was broken. Instead of paper, they washed a rag in the sink.

“We were all taken to the corridor, where they listened to our questions and complaints. They checked us, examining our legs, arms, and torso there.”

After the report, the special forces or warders searched Yevhen’s cell, taking everyone into the corridor. The guards looked through everything, knocking on the toilet and beds with a stick. If one of the prisoners hid something, it fell out quickly.

Yevhen recalls that from 9 a.m. to 12 p.m. and from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m., the Federal Security Service’s officers interrogated them, or investigative actions were carried out. From 12 to 2 p.m., the prisoners had lunch, the cell was cleaned, and at 7 p.m. they had dinner. After 8 p.m., the prisoners had time for themselves.

“Since we were not convicted, we were not allowed to watch TV, so everyone did something different. From 9:30 to 10 p.m., we were getting ready for bed. At 10 p.m., there was a curfew. During the day, three lamps were on in the cell. Two were turned off in the evening, and one was left on.”

Yevhen and his cellmates were taken to the shower room opposite their cell every Wednesday. Each shower room had a 160-liter boiler, but they were taken to the other end of the corridor since it was broken. There was hot water, but it was hard to call it washing.

“We have the 47th cell, and five or six cells are joining us. You come in, and the water is barely warm. We were given 5 minutes to wash, depending on the shift. We would come in, wash quickly, and leave. We were already told: “That’s it, time’s up.” We didn’t have time to dry off, so we put clothes on our wet bodies.”

After the shower, the guards searched Yevhen to see if he had taken anything.

The cellmates told the man they were not allowed to wash in Simferopol’s pre-trial detention center No. 1, so they took cold water in a mug and walked around with it for 1.5 hours to heat it up. This way, they could at least wash themselves and maintain basic hygiene.

“We were taken for a walk to the inner ‘courtyard,’ barely 5 meters square. At its end were two benches. Outside, like in the cell, there were surveillance cameras. We didn’t know if they were recording with sound,” says Yevhen.

Civilian hostages were fed semi-raw potatoes without salt sprinkled with slices of pickles and Korean-style carrots. They were also given cereals (oatmeal or barley) that resembled wallpaper glue and poured tea without sugar. Soups often contained small and large bones.

The former prisoner recalls that the older wardens were more or less regular. But the younger generation was cruel – they liked to mock and beat someone.

“If a normal shift is on duty, the day will go smoothly. When the morons come out, they immediately start saying, ‘Why are you sitting? Why are you sleeping? They threw away all the mattresses.” This was done to see whether we were sleeping or not. From time to time, inspectors walk around the prison and watch. Two or three special forces supported them. The latter were the most brutal.”

“They have statues of Stalin in their offices and portraits of him on the walls.”

Another former hostage, Viacheslav Zavalnyi, said 23 civilians and one 60-year-old territorial defense volunteer were in the cell with him. They were held in one of the pre-trial detention centers in the city of Donskoy, Tula region. The Russians still hold these people, some of whom have serious illnesses. The guards force them to stand on their feet for days, allowing them to sit for only an hour during the day.

“Taking a person from another country to your country and holding them hostage is a serious war crime. My heart hurts for the women and children who found themselves in terrible conditions because of this war unleashed by Russia,” says Viacheslav.

He did not see a lawyer or representative of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in captivity. Instead, he often met with representatives of the Federal Penitentiary Service, who were very similar to the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, also known as NKVD, officers in their “work methods.” The man believes that Russians in their country are reenacting the 37th year of Stalin’s repressions.

“They have busts of Stalin in their offices and his portraits on the walls. So your relatives found themselves in the 37th year of the last century.”

Viacheslav hopes the brave women and men will endure everything and return home. According to him, all the Russian comments we see on social media are accurate: Russians live in the past and want Ukrainians to be like them.

“We have to talk about the terrible conditions in which they hold hostages on all international platforms. Russia is very afraid of this,” says Viacheslav Zavalnyi.