Russia militarizes education and erases cultural identity of children in temporarily occupied Crimea – UN and Amnesty International

Right after Russia’s military operation to seize the Crimean Peninsula, the occupying state imposed its school curriculum in Crimea. According to the United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine (HRMMU) and Amnesty International reports dedicated to the 10th anniversary of the occupation of the Crimean Peninsula, compulsory military education and “patriotic” classes were introduced right after the occupation of Crimea. Then, since the beginning of 2022, students, staff, and parents were often obliged to attend “informational sessions” that justify and promote the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine.

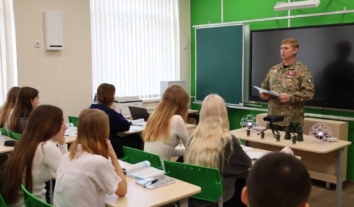

Russia illegally established a network of military-patriotic education centres for Ukrainian youth.

Russia illegally established a network of military-patriotic education centres for Ukrainian youth.Amnesty International indicated differences of opinion are not tolerated, and anyone disagreeing – including teachers, students, and parents – are at risk of reprisals.

In 2023, Crimean experts at the Centre of Civil Education “Almenda” also analyzed in a report the Russian Federation’s use of education for militarization, destruction of Ukrainian identity, and formation of loyal attitudes towards military actions and military crimes committed in Ukraine.

They stated that, since 2022, the “Crimean scenario” of destroying Ukrainian education is currently being implemented in the Russian Federation-controlled territories of the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions. Crimean human rights NGO regularly publishes reports on the violation of children’s rights during the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war.

Training members of the military patriotic social movement “Young Army” in the temporarily occupied Crimea

Training members of the military patriotic social movement “Young Army” in the temporarily occupied CrimeaAdditionally, Amnesty International and HRMMU remarked that by altering the substantive content of the curriculum, Russia has deliberately and systematically restricted access to education in the Ukrainian language. Education in the Ukrainian language has almost disappeared from Crimea.

By the end of 2014, occupying authorities had removed Ukrainian as a language of instruction from university-level education.

In the 2013-2014 academic year, 12,694 students were educated in Ukrainian. By the 2022-23 academic year, only 197 students (0.1 per cent of all students) were fully instructed in Ukrainian.

In addition, only 3,486 students learned Ukrainian as a school subject, an elective course, or an extracurricular activity (according to the illegitimate Ministry of Education, Sciences, and Youth of the “Republic of Crimea.”).

The Crimean Human Rights Group reported in 2017 that only one school was offering education in the Ukrainian language.

In January 2024, the International Court of Justice found the way in which Russia had implemented its educational system in Crimea after 2014, with regard to school education in the Ukrainian language, had violated its obligations under Articles 2(1)(a) and 5(v) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination і .

Amnesty International evaluated the availability of Crimean Tatar language education has been less affected. However, the Council of Europe (CoE) reported in 2022 that schools in Crimea attempt to “imbue schoolchildren with a sense of Russian patriotism and identity, at the expense of their Crimean Tatar affiliation.”

According to the CoE, the new curriculum paints Crimea as historically Russian, thereby undermining the Crimean Tatar legacy as an Indigenous People on the peninsula. It also reanimates old Soviet tropes accusing Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis during the Second World War.

By way of background, long before the Crimean Peninsula was conquered by the Russian Empire under the Empress Catherine II in 1783, various civilizations and cultures intersected and intertwined in Crimea.

The peninsula was inhabited in early times as a crossroad of cultures, peoples, and trade. In the 15th century, the Crimean Khanate emerged and, shortly after its formation, fell under the authority of the Ottoman Empire. During the times of the Khanate, a pre-modern nation of Crimean Tatars was forged.

After the Khanate had been conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire, a large influx of settlers from the Russian Empire changed the ethnic composition of the peninsula. These settlers were particularly from mainland Ukraine, and the influx followed waves of semi-forced displacement and massive political and religious persecution of Crimean Tatars. After the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire, the share of Crimean Tatars living in the peninsula steadily decreased to only 25 per cent in 1900.

At the same time, part of the existing Crimean Tatar settlements were given new names and new towns were founded to be used as fortresses against the armies of Russia’s adversaries in the Black Sea region. The cultures of the indigenous peoples of the peninsula were marginalized by the Russian Empire, and the Crimean Tatar history of the peninsula was being erased.