Human rights defenders criticise the project of exchanging convicted collaborators, “Khochu k svoim”, for civilian prisoners: what is the main concern?

Human rights organisations criticise the state initiative “Khochu k svoim”, pointing out that the Verkhovna Rada has not corrected the shortcomings in the criminal law on collaborative activities. The Human Rights Centre ZMINA believes that the Ukrainian authorities should have chosen another mechanism instead of this project.

Onysiia Syniuk, Legal Analyst with ZMINA, explained this in a comment to CNN.

In May 2025, large-scale prisoner exchanges between Ukraine and Russia began as part of US President Donald Trump’s efforts to try to establish peace between the warring countries. Ukraine handed overі not only Russian prisoners of war, but also at least 120 people convicted or accused of crimes against national security. These were mostly Ukrainian citizens who were convicted of treason, collaborationism, passing information to the enemy, and participation in terrorist organisations.

The exchange programme was initiated last year by the Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, the Ministry of Defence, the Security Service of Ukraine, and the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights.

Ukraine stated that all of those exchanged did so voluntarily under this state programme, which allows anyone convicted of collaborating with Russia to be sent there.

However, human rights groups and international lawyers say the programme is problematic, contradicts previous statements by the Ukrainian government, and could potentially put more people at risk of abduction by the Russians.

“I completely understand the sentiment, we all want the people (who are detained in Russia) to be released as quickly as possible and Russia has no will to do that… but the solution that is offered is definitely not the right one,” Onysiia Syniuk said.

Onysiia Syniuk

Onysiia SyniukIn its article, CNN outlines the phenomenon of Russia’s unlawful detentions of Ukrainian citizens to create an exchange fund and exert pressure on Ukraine. The TV channel cites Ukrainian authorities’ data, according to which the Russian authorities unlawfully hold at least 16,000 Ukrainian civilians, and notes that the real figure is likely to be much higher. Some 37,000 Ukrainians, including civilians, children, and military personnel, are officially reported missing.

Many have been detained in the occupied territories, held for months or even years without charge or trial, and deported to Russia. These include activists, journalists, priests, politicians, and community leaders, as well as people who appear to have been randomly abducted by Russian forces at checkpoints and other locations in the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

The detention of civilians by the occupying power is unlawful under the international law of conflict, except in a few narrowly defined situations and with strict time limits. As a result, there is no established legal framework for the treatment and exchange of civilian detainees in the same way as for prisoners of war.

Last year, Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights Dmytro Lubinets told CNN that Kyiv views Russia’s unlawful detentions of civilians as a means of bargaining and exerting pressure on Ukraine. Lubinets rejected the idea that civilians should be released as part of a prisoner of war exchange. Moscow must release them without conditions.

Relatives and friends of Ukrainian civilians illegally held captive by the Russian Federation in the temporarily occupied territories (TOT) and in Russia are participating in a protest in Kyiv in 2024

Relatives and friends of Ukrainian civilians illegally held captive by the Russian Federation in the temporarily occupied territories (TOT) and in Russia are participating in a protest in Kyiv in 2024The “Khochu k svoim” programme is Kyiv’s attempt to return some detained civilians without recognising them as prisoners of war, which they are not.

However, human rights organisations are calling on the Ukrainian government to continue to put pressure on Russia and insist on the unconditional release of civilians.

“Under international humanitarian law, it is impossible to talk about the exchange of civilians. All unlawfully detained civilians must be released without any conditions,” explained Yuliia Horbunova, Senior Researcher on Ukraine at Human Rights Watch (HRW), adding that in practice it is extremely difficult to achieve this as Russia does not play by the rules.

“For Ukrainian civilians, to be included on an exchange list is their main hope. I think the scheme is an attempt to find a way to do this,” she told CNN.

Petro Yatsenko, a representative of Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War, told CNN that Ukraine did not know in advance whom Russia was returning during the exchanges.

The headquarters reported that among those who returned was a group of 60 Ukrainian civilians who had been convicted of general criminal offences and were not related to the war.

Deputy Head of Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War Andrii Yusov explained that many of them had been convicted by Ukrainian courts and were serving their sentences in Ukrainian prisons when Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022 and occupied the Ukrainian areas where they were held.

After serving their sentences, the Russian authorities were supposed to deport these prisoners from the occupied territories back to Ukraine. Instead, they unlawfully held them in detention centres commonly used for illegal immigrants and released them only in a 1,000-for-1,000 prisoner exchange.

Russia’s Commissioner for Human Rights, Tetiana Moskalkova, described those convicted in Ukraine on charges of collaborative activities and sent to Russia as “political prisoners”, but provided no justification or further details on who they were or what would happen to them. Moskalkova’s office also ignored CNN’s request for comment.

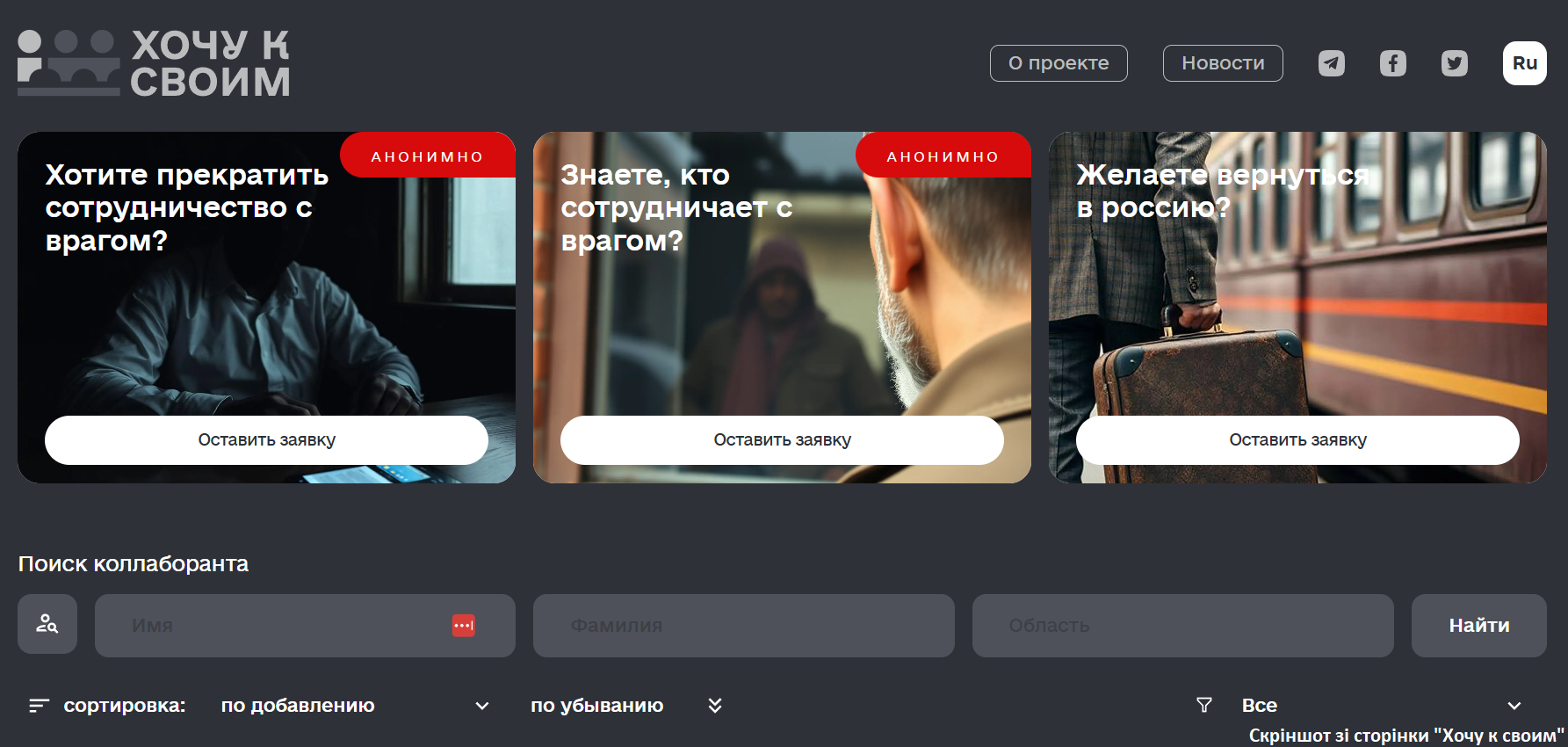

The portal “Khochu k svoim” publishes details of those convicted of collaborative activities who have already been handed over to Russia. Many of them were serving multi-year prison sentences for working for Moscow. Some of them were convicted of supporting the Russian invasion or passing information to the Russians about the location of Ukrainian troops. Most received sentences ranging from 5 to 8 years in prison. However, human rights defenders point to shortcomings in the criminal law regarding collaborative activities.

Read also: Working in the occupied territories: what international humanitarian law says about it

In December 2024, Human Rights Watch published a detailed reportі criticising the anti-collaboration law, calling it flawed.

Horbunova said that the human rights organisation had analysed 2,000 sentences and found that although there were genuine collaborators among them, many of the convicts were “people who, according to international humanitarian law, should not have been prosecuted“.

According to her, Human Rights Watch has seen verdicts in cases where “little or no harm” was done or where there was no intent to harm national security. Some of the cases reportedly involved people who worked in the civil service in areas that were later occupied and who simply continued to do their jobs.

Although the state initiative “Khochu k svoim” website features handwritten consent for the exchange in each profile, human rights organisations say that the way these individuals were renounced by their country is ethically questionable.

“These people are still Ukrainian citizens, and the wording that they have on the website is that they were exchanged for ’real Ukrainians’ – that is very … not okay,” explained Onysiia Syniuk.

On 9 June 2025, President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy stated in his video address that the exchange of prisoners of war with Russia, which had started, would last for more than one day. He said that the details of the process are quite sensitive, so less information is released than usual.

Before that, the Human Rights Centre ZMINA published research on the verdicts issued by Ukrainian courts from 15 June to 31 December 2024. Human rights defenders have found that Ukrainian courts continue to apply a formal approach to considering cases of collaborationism, ignoring international humanitarian law and the real conditions of the occupation. Human rights advocates also pointed to violations of the principle of legal certainty, presumption of direct intent without proper evidence, and ignoring the context of the occupation in the consideration of cases.

During the Coalition Talksі , Olha Skrypnyk, Coordinator of the Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law Group of the Crimea Platform Expert Network and Head of the Board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, shared her belief that cases regarding collaborative activities pose a challenge for the state.

The human rights defender stated that there are currently examples of criminal cases that threaten the successful reintegration of the liberated territories. She believes that the proper regulation of the legislation on collaborationism will determine how quickly Ukraine can restore normal life in these areas.

Earlier, during the presentation of the Shadow Report to the European Commission, the Head of the Human Rights Centre ZMINA, Tetiana Pechonchyk, explained that, unlike other EU candidate countries, the state must provide answers and develop approaches to a number of challenges during the de-occupation and reintegration of the liberated territories.

By way of background, on 21 January 2025, the coalition of organisations dealing with the protection of the rights of victims of armed aggression against Ukraine announced 13 Priority Steps for the Verkhovna Rada and the Cabinet of Ministers to protect human rights in the context of armed aggression against Ukraine for 2025.