Russia needs soldiers. The Global South has desperate people. The rest is exploitation.

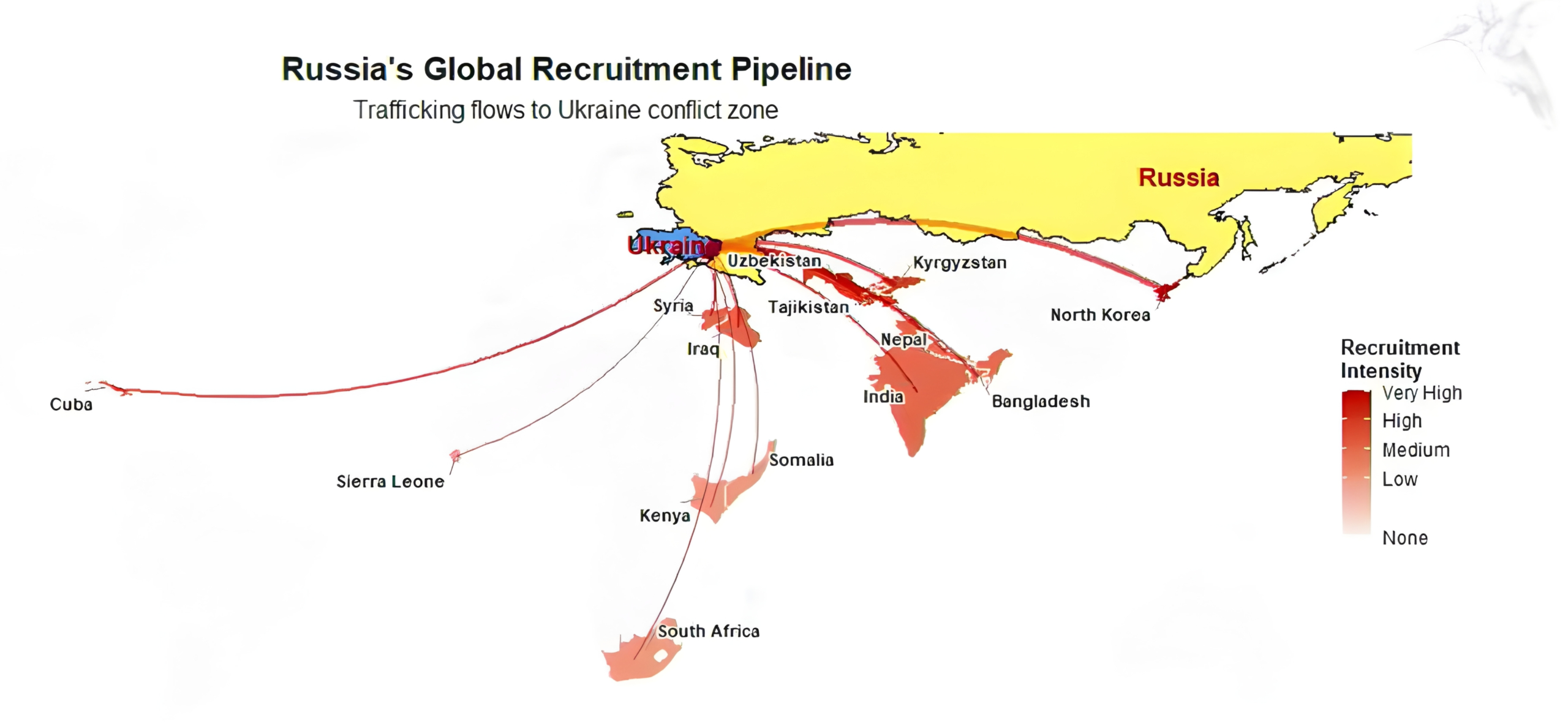

Russia loses approximately 1,000 soldiers every day in Ukraine. To maintain current force levels, Moscow must generate between 30,000 and 40,000 new recruits each month. After mobilization in September 2022 prompted more than 261,000 Russians to flee the country, Putin found a third option: build a global trafficking infrastructure that spans from North Korea to Cuba, Nepal to Kenya, exploiting economic desperation to fuel a war that distant populations have no stake in, explained Munira Mustaffa, Senior Fellow at Verve Research at the Third International Conference Crimea Global.

ZMINA has recorded her speech during the conference.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has lasted for the third year, and while much attention has been paid to battlefield developments, there’s a darker dimension of how Moscow is sustaining this war that deserves closer examination.

A Crisis Kremlin Won’t Acknowledge

To understand why this recruitment pipeline exists, we need to start with a crisis that the Kremlin refuses to publicly acknowledge. Russia has sustained over 1 million casualties since February 2022, with approximately 1,000 personnel lost every day. Just maintaining current force levels requires Moscow to generate between 30,000 and 40,000 new recruits each month.

This creates two critical problems. First, there’s the financial burden. Russia’s volunteer recruitment system depends on ever-escalating cash incentives that are draining state coffers and destabilizing domestic labor markets.

Second, mass mobilization is political suicide. When [accused of war crime by the International Criminal Court, Vladimir] Putin attempted mobilization in September 2022, over 261,000 Russians immediately fled the country. So Putin needed a third option, and he found one. In July 2025, he signed a decree that may have seemed bureaucratic on the surface, but was strategically significant.

How Russia Industrialized Expendable Warfare

The decree authorized foreign nationals to serve in Russia’s military during periods of mobilization. What makes this particularly noteworthy is what the decree doesn’t say. It provides no specifications for how these foreigners will actually be recruited. The legal ambiguity is not an oversight; it’s deliberate.

Unwilling to risk another round of domestic mobilization, Putin has built what amounts to a global trafficking infrastructure.

North Korea provides the most formalized arrangement — over 10,000 soldiers, complete with a mutual defense treaty signed in June 2024 that echoes Cold War-era military alliances.

Central Asia represents a model entirely different. Russia hosts approximately 3 million migrants from this region, and we are now seeing systematic workplace raids where these individuals face a difficult choice: military service or deportation.

The Economic Trap

But the network extends far beyond these regions. Syria was reportedly the earliest major source with recruits sent for training in Russia following the 2022 invasion, while Bashar al-Assadі was still in power. By late 2023, Cuba‘s own foreign ministry had uncovered human trafficking rings recruiting Cuban nationals.

You may also want to read: Ukraine closes Cuba embassy and downgrades ties over Havana’s complicity in Russian aggression

But the network extends far beyond these regions. Syria was reportedly the earliest major source, with recruits sent for training in Russia following the 2022 invasion while Assad was still in power. By late 2023, Cuba’s own foreign ministry had uncovered human trafficking rings recruiting Cuban nationals.

From there, the networks spread across South Asia to Nepal, India, and Bangladesh; across Africa to Kenya, Somalia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa; and, most recently, to Iraq.

What links these diverse countries together is a common vulnerability — economic aspirations combined with institutional weaknesses that prevent governments from adequately protecting their citizens from predatory networks.

Strategic Evolution: From Chechens to Global Trafficking

It’s crucial to understand that this didn’t just emerge from desperation. It’s the result of strategic learning over time. The conceptual foundation came from the Chechen paramilitary led by Ramsan Kadyrov. They suffered catastrophic losses at the Battle of Hostomelі . They earned the unflattering moniker “TikTok Warriors” for their reluctance to engage in such combat.

Despite being a PR disaster, they proved something important to Moscow. You could wage war through expandable proxies. Then Wagners took that concept and industrialized it. [A Russian mercenary leader, rebel commander, and oligarch] Yevgeny Prigozhin went directly into Russian penal colonies, offering prisoners a bargain: fight as expendable assault troops in exchange for reduced sentences.

When Prigozhin launched his mutiny in June 2023 and died in the plane explosion two months later, many assumed Wagner was finished. But the model outlived its creator. Putin’s July 2025 decree simply took what Wagner had proven to be effective and scaled globally.

The Global Recruitment Pattern

The actual recruitment follows a remarkably consistent pattern across all these countries. Networks operate by making false promises — construction jobs, warehouse work, and sometimes even suggesting that this could be a pathway to eventual citizenship in Europe.

The war itself has amplified economic desperation through cascading effects on food security and energy prices, making these promises more attractive to increasingly vulnerable populations.

What enables this system to function is institutional weakness. Governments already struggling with political instability simply cannot protect their citizens from sophisticated trafficking networks masquerading as legitimate employment agencies.

In some cases, particularly among certain African states, there appears to be minimal interest even in attempting repatriation.

This structure is not entirely without precedent. There are striking parallels to another exploitation system currently operating in Southeast Asia — cyber scam compounds. In places like Myanmar, state collapse and civil war create perfect conditions for trafficking networks to operate. Both systems — the scam compounds and Russia’s recruitment pipeline — share a defining characteristic: They weaponize forced criminality by transforming victims into perpetrators.

This is strategically significant. Once someone has been coerced into participation—whether running romance scams or fighting in the trenches—they become nearly impossible to prosecute, and rescue efforts essentially collapse.

Gray Zone Warfare

Meanwhile, those who actually design and orchestrate these systems remain insulated behind legal ambiguities and jurisdictional gaps.

This brings us to why Russia’s recruitment pipeline exemplifies gray zone warfare — operations conducted below the threshold that would trigger a formal international response while achieving strategic objectives through deliberately ambiguous means.

The legal ambiguity is not accidental. It’s the entire point. Are these individuals mercenaries under international law? Are they volunteers, or are they trafficking victims? The deliberate opacity makes prosecution nearly impossible while allowing Russia to maintain some veneer of legitimacy. By using third-country nationals, Moscow obscures responsibility, complicates any international legal response, and exploits diplomatic blind spots, particularly in non-aligned states.

Recruiting foreign fighters is not inherently illegitimate in contemporary warfare. Ukraine, as we know, operates an international legion, and they do so through transparent government channels.

They have certainly faced challenges — mismanagement, vetting failures, allegations of poor conditions — but these reflect organizational problems. The fundamental difference here is structural. Russia’s model depends on systematic deception, human trafficking, and exploitation of populations who have absolutely no stake in this conflict’s causes or outcomes.

Part of Russia’s Broader Strategy

The recruitment pipeline does not exist in isolation. It is part of Russia’s broader gray zone strategic toolkit. We see similar approaches in sabotage operations targeting European infrastructure, sophisticated disinformation campaigns, and ongoing subversion efforts directed at Western institutions.

The recruitment pipeline serves multiple functions simultaneously. It sustains Russia’s war of attrition without triggering the kind of domestic political crisis that mobilization would inevitably cause.

Foreign casualties conveniently don’t appear in the statistics that Russian domestic audiences see.

The system weaponizes the very desperation the war creates. Food insecurity and energy crises have made vulnerable populations more susceptible to false promises.

Western strategy faces an uncomfortable paradox. Sanctions constrain Moscow economically, but they don’t end the conflict. They drive Russia to exploit vulnerable populations as an alternative. As economic pressure intensifies, Moscow’s incentives to escalate global labor recruitment may grow stronger.

You may also want to read: Ukraine calls on world not to ease sanctions against Russia until it frees all Ukrainian people and territories, including Crimea

Simultaneously, Western attention fragments across multiple crises, weakening international consensus against predatory recruitment practices as gray-zone pipelines expand, rather than contract.

A Moral Catastrophe We Refuse to Name

Where does this leave us? The fundamental question is no longer whether Russia can afford to continue fighting. Moscow has clearly demonstrated that it can lure foreigners into the meat grinder to avoid another domestic mobilization.

The actual question that we need to confront is this: How many more people must die before the international community acknowledges that this is a moral catastrophe?

For countries across the Global South, the lesson is obvious — non-alignment offers no protection from great power competition when poverty renders your population vulnerable and exploitable. For the West, policies like the Trump administration’s tariffs and the U.S. aid cuts deepen the economic desperation that Russia weaponizes as a recruitment tool.

Russia needs soldiers; the Global South has desperate men and women. The rest is exploitation.

Stay connected via X and LinkedIn with ZMINA – and help build this platform with us by filling out our anonymous 5-minute survey here.