Road for survival. How Ukrainians from occupied South cross Vasylivka to break free

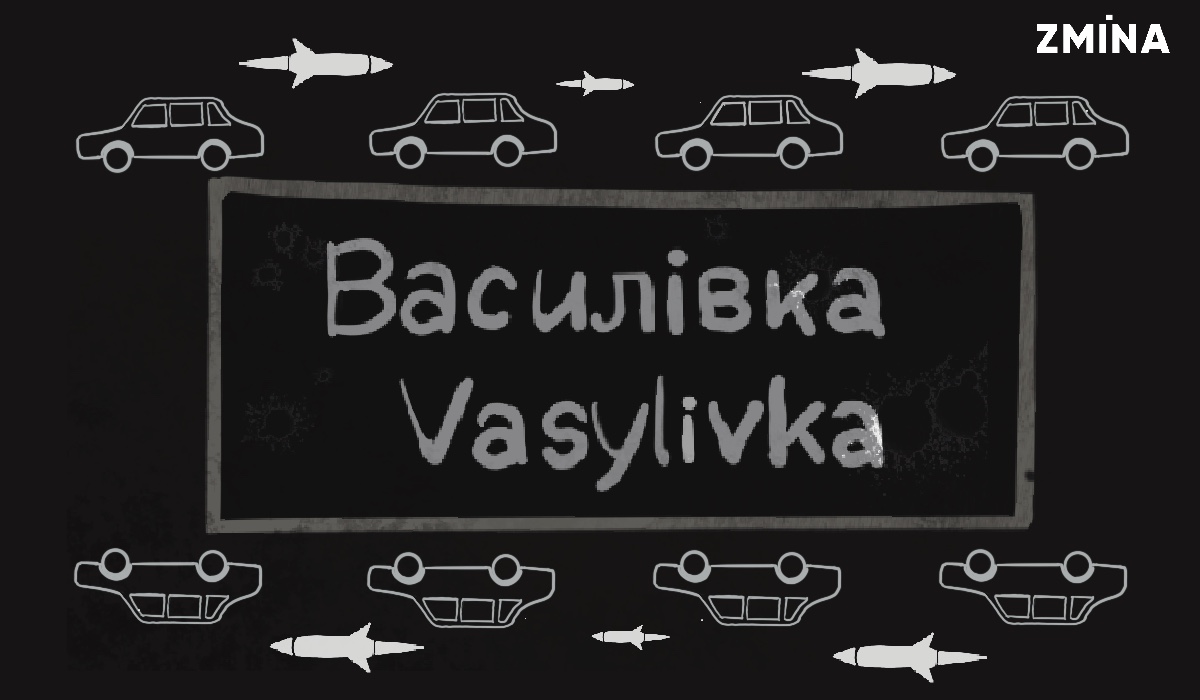

Vasylivka is a town located on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir in Zaporizhzhia region. Russian troops occupied it back in March. Since then, according to Vasylivka Mayor Serhiy Kaliman, almost 80% of the residents have left the town. Currently, the road through Vasylivka to Zaporizhzhia is the only way to get from the occupied South to the territory controlled by the Ukrainian government. People get on the road at their peril and risk as there are no official “green corridors”.

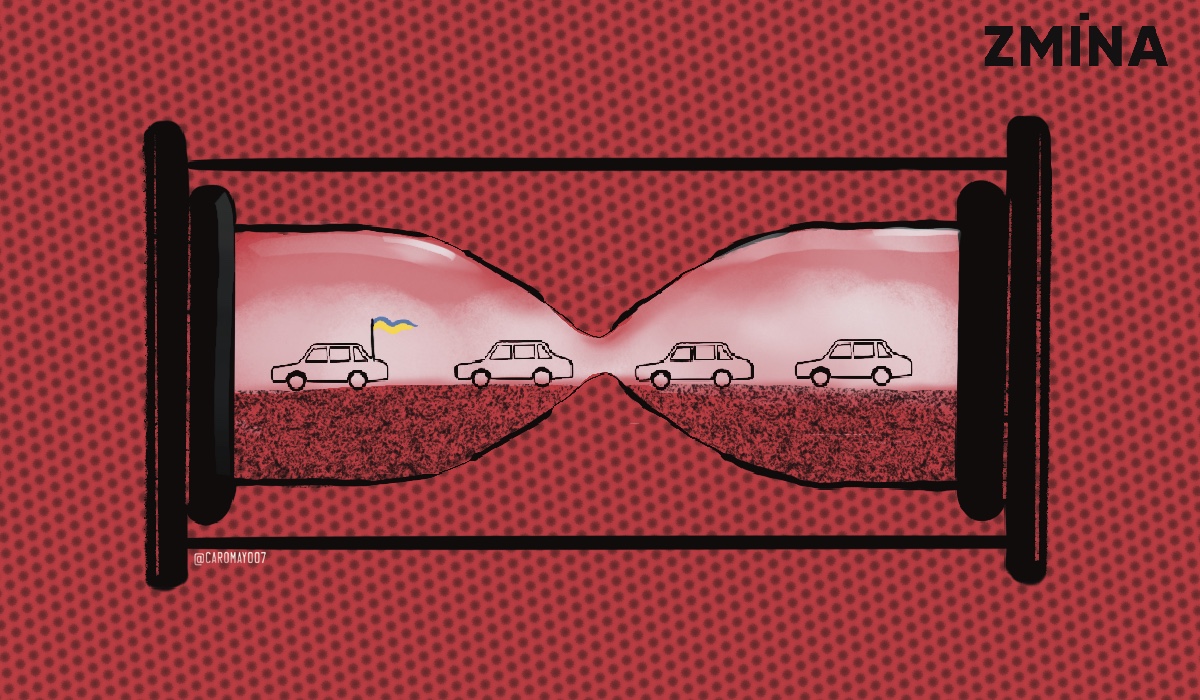

Serhiy Kaliman compares the town to an hourglass: Vasylivka is the narrowest place through which every grain of sand passes. It has such a location that the residents of Kharkiv, Poltava, Dnipro, and Zaporizhzhia cities, all who went to, for example, Kyrylivka, Henichesk, Melitopol, had to drive through Vasylivka.

Therefore, it is not surprising that the Russians took advantage of its geographical location, Serhiy Kaliman explains. There are queues to Vasylivka from Melitopol and Dniprorudne and in the opposite direction from Zaporizhzhia. The Vasylivka Mayor states that the Russian military shielded themselves with civilians from everywhere.

ZMINA talked to people, volunteers, and drivers who crossed the checkpoints in Vasylivka. In a few months, they turned into a separate world, subject to the changing mood of the occupiers – lawlessness reigns here, people have to spend nights by the road in tents and cars or neighboring villages, undergo humiliating inspections, and do not have access to healthcare. The physically and psychologically exhausting wait for departure has already claimed the lives of more than ten people.

This article tells how the Russians artificially create queues at the checkpoint in Vasylivka, using civilians as human shields.і

Anastasia. Kakhovka–Vasylivka–Zaporizhzhia–Odesa

Anastasia, a resident of Kakhovka, is one of those who had to cross the checkpoint in Vasylivka. Some of her acquaintances left the town back on February 24, the day hen Kakhovka was captured by the Russian military.

“I don’t know how people gathered their thoughts and strength. I’m not a person who makes decisions so quickly,” she admits.

Therefore, the girl stayed at home with her one-year-old son and her husband.

“Russian world” came to us step by step,” Anastasia recalls, “Why does a Ukrainian town suddenly turn into a mess at the will of some person? How did it happen that we are called another country? All that seemed unreal.”

She went to rallies against the occupation. Then, unlike Nova Kakhovka, there were no Russians and their military equipment everywhere in Kakhovka.

However, the situation gradually worsened and people began to disappear.

“And then it became really scary. It’s as if we wrapped ourselves in a cocoon in our home, in our world, in the circle of relatives and closest friends. We lived in our parallel reality. We did not reveal our position extra time, were constantly anxious, cleaned up phones. We didn’t even go outside the town during all that time. The longest root was to walk from home to a market or embankment. The world narrowed much. We found ourselves in a kind of prison,” the girl describes life under the occupation.

Locals started to leave Kakhovka massively in April. The Russian side did not agree on any “green corridors”, so people escaped by the roads they found. Anastasia heard sometimes from acquaintances or relatives the stories about the shooting of cars.

It was frightening and for several months discouraged the idea of leaving.

The girl dared to evacuate only when people began talking about a counteroffensive of the Armed Forces of Ukraine in the South of Ukraine. It was also becoming more dangerous in Kakhovka itself. The Russians placed their repair bases here. In the mornings, they saw missiles fired at Mykolaiv flying over their town more often.

Anastasia began following a Telegram group where people shared their evacuation experiences. For a long time, she studied the nuances of crossing checkpoints.

Finally, at the end of July, the family got into a car and drove away – Vasylivka remained one out of all possible options for crossing the contact line. They took things with them, a thermal bag with food, a car cover, water, a thermos, toys for the child, downloaded cartoons on the phone. The girl’s parents and relatives were going by another car. They reached Vasylivka from the side of Dniprorudne.

Anastasia recalls:

“On the first day, everything was quite confusing: you don’t understand how the queue works, how to find out how many cars are ahead of you. It was like 250, but it’s difficult to say for sure.”

The family spent that day in a queue. The son was bored. The air temperature reached 35 degrees Celsius.

Cars turned into red-hot pans in such heat:

“That’s why all these nuances are so important – to cover a car, freeze the water so that the products are kept cold as long as possible.”

The roadside was dirty with human excrement and garbage.

“We spent the night in the village of Skelky. We rented one and a half rooms for seven people. My father was sleeping outside in the car. In the morning, everyone returned to the queue. Only I and my son asked the owners of the house for permission to stay. My son was entertained with chickens and ducks,” the girl recalls.

The Russian military let the cars through slowly, so the queue hardly moved. On the second day, about a hundred cars were let go. At night, everyone returned to the village, returning to the queue in the morning again. Then everything repeated.

Only on the fourth day, Anastasia’s family found themselves among 40 cars that had a chance to leave:

“I think the orcs deliberately created such a situation. Sometimes they let cars go in the morning, sometimes in the evening. There are no rules. They do what they want. Finally, our two cars were inspected. We took all the things out of the trunk and showed everything that was in the bags. Laptops and tablets were inspected in a separate building. On the eve of departure, we cleaned them of everything that could seem suspicious.”

Anastasia’s parents and relatives were asked where and why they were going out. There was a relative with kidney disease with them, who explained that she needed treatment:

“And what else we had to say? You will not tell them: ‘We are running away from you’.”

Those dialogues looked like this:

“Why don’t you go to Crimea for treatment?”

“My children live in Odesa, I have no one in Crimea.”

“What kind of children do you have if they don’t visit their mother? Are you going to come back?”

“I hope so.”

“And we won’t let you in.”

The inspection of ten cars lasts from half an hour to an hour, the girl continues:

“The Russian servicemen are looking at gadgets, and you involuntarily worry whether you deleted everything there and what they will do if they find something there. They exert psychological pressure. It seems to me that they do everything they can so that people do not want to leave and are afraid to do so. After all, everyone has a different endurance threshold.”

In the end, the column in which the family was traveling was let go. But when it seems that the worst is over, there is a grey zone ahead and the risk of shelling. Cars have to rush here.

“A dirt road was washed away by rain the day before. There was complete mud. We slowed down in the grey zone because some cars got stuck. They were pulled out by our Emergency Service workers who are on duty there. When my husband saw one of them, he rushed to hug him, we felt so much joy,” Anastasia recalls.

While people were waiting for the cars to be pulled out, the shelling began. The explosions sounded nearby. The husband reassured Anastasia:

“Don’t worry, these rockets are fired from here.”

And only later did he admit that the Russians were firing at them, and a bumper of one of the cars at the end of the column was pierced by a shell fragment.

“It’s good that my son is too young to understand anything. We closed the windows in the car to make it quieter and I hugged him. People left the grey zone with tears in their eyes and having taken sedative pills. Because you’re sitting in the car and you can’t do anything, only your hands are trembling. Our guys, the Emergency Service personnel reassured us, saying that this happens all the time, and if the Russians wanted to hit a column, they would have hit it a long time ago. This is such an element of intimidation,” the girl explains.

Passing devastated villages, destroyed houses, mines on the roadside, unexploded ordnance, the convoy reached Zaporizhzhia:

“When we got there, the moral and psychological exhaustion was so strong that I even couldn’t rejoice. On the contrary, thoughts tormented me: ‘Why have we done this, we’d better stay at home, why did we leave.’ Apparently, it is this feeling that they strive for with all their actions. It is not for nothing that they ask: ‘Why are you leaving, do you live badly here?’ You have to be a fool not to understand that people are running away from their ‘Russian world’. “

In the morning they realized that they were free:

“This is our territory, we will be protected here. We have rights and freedoms here. And there we actually turned into hostages.”

Currently, Anastasia is in Odesa. Six months ago, a trip from Kakhovka to Odesa took four hours. Now it takes six days.

Artificial barriers

Not everyone can overcome the difficult and dangerous way through Vasylivka. The physically and psychologically exhausting wait for departure has already claimed more than ten lives.

According to Melitopol Mayor Ivan Fedorov, the slow movement of cars is a situation artificially created by the Russians by allowing cars to pass in groups.

“A commandant is a person who acts depending on their mood. A commandant decides how many cars are allowed to go further. And this is a certain humiliation, an element of pressure and intimidation. We are not allowed to feel like people. Filtration also happens differently. But laptops, flash drives, and food are taken from many. At least I know a lot of such facts,” he says.

At the same time, the flow of those willing to leave is large, albeit wavy. For example, several factors led to another wave of evacuations in Melitopol. First of all, the upcoming military operations and shelling. The second factor is the problems of the upcoming heating season. And the third, of course, is the beginning of the school year.

“A large number of our residents were waiting for the de-occupation, they hoped that the children would be able to go to their schools. But since it did not happen, now they want to leave,” explains Ivan Fedorov, “In general, the occupiers try to intimidate Melitopol residents in different ways. Now there is a new scarecrow. They say that they will not let children out of the town after September 1. It is difficult to predict whether it will be so or not. But such psychological pressure is exerted. And of course, people want to escape from it.”

In the same way, the Russian military disseminated information that they would require a pass issued at the commandant’s office allowing the departure from the town:

“To reduce a queue in Vasylivka, when it became the longest possible, the Russians said: ‘You may stand or not, there will still be passes from Monday, and you will all go in the opposite direction.’ But there are no passes still.”

Ivan Fedorov believes that the occupiers want people to be afraid to leave so that more residents remain in the occupied territory:

“Because, first of all, they need a picture showing that the town lives a normal life, that everything is fine in the town. And, second, people who remain in Melitopol are used as a human shield.”

The road through Vasylivka is not an official humanitarian corridor. The situation here is constantly changing. This applies to both crossing rules and queue length. In addition, Ivan Fedorov says, it cannot be ruled out that the Russian occupiers will eventually close this route from the occupied territories.

Mykhailo. Kherson—Vasylivka—Zaporizhzhia—Zhytomyr

Mykhailo, a programmer by profession, lives with his family 5 km from Chornobayivka, Kherson region. For five months, they were waiting for Kherson to be liberated. In the end, they decided to leave to be as far away from the hostilities as possible. Besides, a new school year came, and children have to study. Mykhailo and his wife have four of them: a two-year-old son and three daughters aged 8, 18, and 22.

“Teachers and healthcare workers refuse to cooperate with the Russians. They quit their job. It is increasingly difficult to live in Kherson. And at the same time, it’s scarier. People are kidnapped, tortured in basements,” says Mykhailo, “On July 30, my friend went missing. It is currently unknown where he is. He is allegedly held captive because he went to a pro-Ukrainian rally and was captured in a photo. They came home to another friend. They held him for five days, threatened him, but then released him. He immediately left Kherson with his wife and small daughter. I have an acquaintance who worked as a tester in an IT company. She volunteered. She was abducted from her home in mid-May and her fate is still unknown.”

At dawn on July 31, Mykhailo’s family left their home and headed along the Beryslav highway through the Daryivka Bridge, Kakhovka HPP, Melitopol, and towards Vasylivka. There were two adults, three children (the eldest daughter left a week earlier with her boyfriend), and two dogs inside a car. Nine cats were sitting in specially equipped cages in a trailer. Mykhailo’s wife was driving.

The family was preparing to leave:

“We read the group ‘How to leave Kherson’. We knew what we will go through, how it happens, where and in what direction we should go. The day before, perhaps the most frightening thing was that we would have to live in the queue near Vasylivka in the heat for a long time. This fear came true. We spent there four nights, and they let us go only on the fifth day.”

There were 30 checkpoints on the road to Vasylivka. Every car was stopped and documents were checked at each of them. At two checkpoints, Mykhailo was asked to take off his T-shirt and show his tattoos. At several more, they checked what the family was carrying in the trunk and trailer. They asked where they were going. Somewhere near Kherson or Kakhovka, Mykhailo said that they were going to Melitopol, and in Melitopol – that they were going to Vasylivka:

“Already near Vasylivka, we were asked why we were leaving. We told the truth that we were taking the children to a safer place. It was unpleasant to talk with them. These are people you did nothing bad to, but they came with weapons and took everything from you. But you have to control yourself.”

From Melitopol, we drove straight along the highway until we saw a queue of cars. At first, we noticed trucks and then we saw a gas station by the road and many cars at it:

“We joined an ordinary queue. It was the 79th column. A column usually consists of ten cars (8 cars and two vacant places kept by the Russians in the column to add someone as they wish). But we were advised to sign up for a preferential queue. Allegedly, they pass it faster because there are children, people with disabilities, and pensioners.”

But it still didn’t work out faster.

“The Russian military let cars go little by little. Only at certain hours. Overall, as they like. They can let one or two columns go in the morning, several more in the evening. Or they don’t let anyone out for the whole day.”

Mykhailo does not doubt that the Russian service members deliberately create queues:

“This is pure abuse. After all, different people stand in a queue. I remember a woman at 38 weeks pregnant in the preferential column. She was the most remarkable, although there were other pregnant women, children, and old people. She, like everyone else, slept under the open sky.”

All this time the family lived at the gas station. First, at one, and then, as the queue advanced, they moved to another. Staying on the highway is prohibited. Russian trucks are moving along the road at high speed. And even at a gas station, people advised the family to stay away from the highway: there were cases when Russians on an armored personnel vehicle drove into the gas station at high speed.

“While we were there, some guy was constantly riding a beautiful new motorcycle. He must have taken it from someone. He could ride along the highway, but he deliberately rode in the area where people were sleeping. In the evening, he began to drive by the gas station, where children were running, adults were setting up tents. But what will you do to him?” Mykhailo wonders.

His children and wife were sleeping in the car. He spent the night in a tent. And everything would have been fine, if not for heavy thunderstorms two nights in a row. It was uncomfortable to sleep, it was wet and cold.

“The second night of rain was the hardest for me. I understood that the road was completely washed away. And we have a small car and a trailer. I was worrying that they would let us out in the afternoon and we would be stuck.”

The column was indeed checked the next day, but a commandant turned it back.

“During the inspection, all our things were searched through, including underwear and socks. This is a humiliating procedure,” Mykhailo admits.

The family spent the next night in the field again and left when it dried out a little.

Now they are in Zhytomyr. They plan to live here until Kherson is liberated and hope to return home then.

Departure queues

“Evacuate. A difficult winter is coming. We need to help you, save you from cold weather and the enemy,” Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk called on the residents of Kherson region at the opening of the Support Center for IDPs in Zaporizhzhia in August.

It’s easier to say than do it. Not everyone has the opportunity to leave by their own transport or with private carriers, who set the price varies from 3,000 to 7,000 hryvnias.

A significant number of people are waiting in line for free evacuation, which is carried out mainly by volunteers.

Olena helps one of the volunteer associations that transports people from Kherson region free of charge. Since the end of April, the team has helped 3,000 residents of Kherson region, who cannot afford to evacuate on their own, to get out.

“When there was a call on all TV channels to ‘leave’, we receive application after application. About 500-600 people applied a day. Can you imagine the flow? We don’t transport that much in a week,” Olena says, “now I have a list of applications with almost 10,000 lines in front of my eyes.”

Some have been waiting for their turn since May. There are thousands of applications, but the team can take out 300 people a week at best. There is not enough transport. And the situation is getting worse every day.

“Bridges are damaged, cars are let go slowly in Vasylivka. Sometimes the weather intervenes. Once the road was so washed away that a bus spent the night in the grey zone. And it was scary because there was a woman in it who was due to give birth in two weeks,” says the volunteer.

Other volunteers face similar problems. One of them is Stefan Vorontsov, co-founder of the Humanity volunteer organization, which has been helping Nova Kakhovka residents to leave since the beginning of the large-scale invasion.

“Initially, it was like this: someone doesn’t have enough funds, we pay, a person leaves. But now there is a completely different flow,” he says.

Now they have 300 requests pending. This is about 900 people. Humanity already has one evacuation bus. But this is not enough. Currently, the organization has accumulated funds and is ready to purchase additional transport and pay drivers.

Stefan says that fewer people were willing to leave when there were no strikes:

“Everything changed after the first strike on Nova Kakhovka on July 12, when the Ukrainian military hit an enemy ammunition depot. A huge queue was formed. Thousands of cars stood in Vasylivka. We even wanted to wait out, not to accept applications, we thought that the flow would subside. But it did not. Just today I looked at what is written in Telegram group: hundreds of cars stand both from Dniprorudne side and Melitopol side. People say that the orcs are tired today and are taking a day off. They don’t let anyone out.”

Usually, Russians let 100-200 cars go a day. It’s a miserable amount, Stefan says:

“Our military cannot start moving in that area because the queue does not disappear, there are always many people in it. And the Russians have two directions actually covered up. Our people also do harm, making it difficult for the queue to move as they get drunk. They quarrel, take pictures, make videos. Orcs see it. And as a “punishment” they may not let cars out. To drive faster, you need to go to a checkpoint and negotiate. You understand that agreements are made not only with words. And this is probably another reason for a queue.”

Stefan emphasizes that the road is incredibly difficult physically, morally, and mentally. In the queue, people have already had strokes, heart attacks, and there are cases of dysentery. There are no toilets or showers. There is technical water, but there is no healthcare assistance, there are no shelters.

“Orcs don’t care. It would be surprising if they cared about it. But the biggest trouble that can happen is rain. Autumn is coming. And it’s terrible,” the volunteer speaks about the danger of the road being washed away.

A trip is also dangerous for the drivers themselves. According to Stefan, five drivers from Kherson region, who cooperate with volunteers, were searched. One female driver was taken away. Her whereabouts are unknown.

Ihor. Transporter

Ihorі , a native of Kherson region, has been engaged in passenger transportation for 20 years. He organized the first evacuation routes in April on his own. Those willing to leave far exceeded his possibilities.

“It was dangerous to drive through Snihurivka and Davydiv Brid. Now it is the same with Vasylivka, which remained the only way out of the occupied territories. Shelling is the worst thing. Only God helps everywhere,” he says.

Ihor is currently cooperating with one of the volunteer organizations that evacuates people from the occupied South for free:

“The Russians brought the flows out and in into one point – Vasylivka and centralized everything. This is more profitable and easier for them as making other transitions means scattering their strength,” he explains.

Drivers try to do everything possible not to spend the night on the road as it’s very difficult to do with a full bus.

“Actually, our volunteers went straight to the Russians at the checkpoint and explained that there were women, small children, pensioners, and the sick in the bus, asking to let us go. We continue to try to use this scheme. Although it works once in a while.”

All drivers who go to Vasylivka are being trained. They are instructed on how they should behave. The main rule is not to participate in conflicts.

“If there are several of our buses, the first is the one who already knows the situation, all the nuances, what to say and how to communicate with the Russians. Because they are very specific people. They like others bow before them and beg,” Ihor says.

He is often asked how to behave at a checkpoint during an inspection. So he advises:

“Behave naturally. You are at home, and they are on a visit. When Russians ask where I transport people, I say: ‘I transported them many times before and I never asked where they were going. People have their reasons. Students take exams, some go to relatives, and some go for treatment. I cannot answer for everyone. Go in and ask them.’ I noticed, by the way, that when there are many people on a bus, Russians behave with caution.”

On the way to Vasylivka, you have to pass many checkpoints. Somewhere, the military doesn’t even enter a bus, somewhere they look through men’s passports. Somewhere all the men have to leave a bus with their belongings, they are asked where they are going, why, whether they served in the army or not, what is their job. There were incidents when men were taken from the bus.

People’s main enemy during inspections is their phone, Ihor explains:

“Everyone knows that it needs to be cleaned up but to a certain extent. Because someone deletes everything. Then they [occupiers] start to nitpick, ask leading questions. And God forbid, they will find some video on a phone with the word ‘orcs’. They lose their temper seeing this. They take a person away and begin to put psychological pressure.”

At Vasylivka, the entire bus is unloaded down to the smallest piece of luggage: everything must be taken out, all the glove boxes must be opened.

Ihor admits that evacuation buses that bypass the queue make people on their own cars from the queue very angry:

“Everyone is psyched and tired. There were cases when people blocked our way. My windshield was broken once. I try to explain to them that I am transporting people who cannot get out on their own, and I have to go back for the others.”

But the most difficult thing for Ihor is the grey zone. This section of the road takes 40 minutes, but it is the most dangerous. Ihor always tries to drive as fast as possible through it. The scariest part is a gully. It is 500 mF, and even has a little downhill in one place. You can get stuck if the road is washed away. And Ihor did get stuck.

So he had to spend the night in the grey zone, he recalls:

“Imagine, first, people drive through this destroyed road, then they get stuck in a gully, the shelling begins. I saw how the truck’s glass was blown out by a blast wave. It exploded very close. It thundered all night. Russians intimidate so. Or they do it as a farewell, to catch up. They let columns out and start shooting immediately. They believe that we should be with Russia, and if we are running away, then we are traitors to them. They have fun like this.”

Violation of international law

“The situation in Vasylivka is a serious violation of international humanitarian law. It may fall under the definition of a war crime in accordance with Article 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court – committing outrages upon personal dignity,” comments Vitalia Lebid, a lawyer at the Center for Strategic Affairs of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union.

Russia, as an occupying power, has certain obligations to protect and ensure the rights of the civilian population under occupation. They are provided for by the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.

First, the Convention guarantees the right to humane treatment, respect for human honor and dignity. At the same time, the right to personal freedom and freedom of movement is an integral component of respect for a person under the Geneva Convention.

“It is natural that it can be restricted during hostilities. But only in circumstances that pose a threat to life and health of people who leave. That is, the occupying power can introduce such restrictions or even a ban on leaving only to protect the civilian population,” the lawyer explains.

Second, Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention directly states: the occupying power shall not detain people in an area particularly exposed to the dangers of war.

Unless the security of the population or imperative military reasons so demand. Lebid notes that only one of these two conditions can, depending on the circumstances, justify the prohibition of the right to leave:

“In any case, there must be a real necessity. And the measures taken must not be used as a punishment or a method of inflicting suffering. Moreover, such measures must not somehow serve the interests of the occupying power.”

Considering the situation in Vasylivka, Russia artificially creates obstacles for the civilian population to leave the occupied territory, the lawyer concludes:

“And this cannot be justified by any goal of protection. On the contrary, this is done to cause additional suffering to Ukrainians who escape the consequences of Russia’s aggression. This is evidenced by the very procedure of special detailed checks of people leaving, inspections, searches, seizure of personal belongings which definitely causes additional stress, psychological strain, and are generally degrading to human dignity.”