One day with volunteers in the destroyed Vuhledar, Donetsk region

Before the full-scale Russian invasion began, the mining town of Vuhledar in the Donetsk region was home to 14,500 people. As of July this year, according to the military administration, up to 100 people remained there. Fighting for the town has been ongoing for a year and a half, as Vuhledar is strategically important due to its nearby railroad and highways.

Now, the city looks like a complete ruin. Among the remains of houses, there are pillars of smoke from constant shelling.

However, the people who stayed here need food, water, and at least basic living conditions. This is what volunteers are helping with. In Vuhledar, they have set up a resilience point where residents can safely collect water, shower, charge their gadgets, and even watch Ukrainian TV.

The ZMINA journalist, together with volunteers Andriy and Roman from the Lion’s Heart military volunteer association, managed to get to Vuhledar, which was burned by Russian shelling, and saw with her own eyes how this point of invincibility was being equipped.

A dirt road with a maze of potholes from numerous rains and trucks leads to the city.

What comes into view is hardly a city – just destroyed and burnt houses in black smoke from new hits. Even though the area of the town where the volunteers are going is located farther from the contact line, the Russians have destroyed every single house here.

Although the enemy could see to their destination, the volunteers were surprisingly lucky to get there without coming under targeted fire.

Once residential buildings in Vuhledar after Russian shelling. Photo: Albina Karman

Once residential buildings in Vuhledar after Russian shelling. Photo: Albina KarmanPerhaps the only island of life in Vuhledar is the point of invincibility. This is a small dungeon with dim light and white and pink walls, which volunteers from the Unbreakable group are equipping. They came from Irpin to Vuhledar in early September and started repairing one of the basements.

A few minutes after their arrival, volunteers from Lion’s Heart and Unbreakable form a single chain from the car to the basement to unload the food packages. Without lights, wearing helmets, and listening to heavy sounds, it’s like working in a mine. At the same time, explosions are heard around them.

Volunteers unload food parcels near the invincibility point. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers unload food parcels near the invincibility point. Photo: Albina Karman Volunteers Roman and Andriy brought food packages to Vuhledar. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers Roman and Andriy brought food packages to Vuhledar. Photo: Albina KarmanWhen we went to the basement, we saw volunteers drilling a well so that people could draw water. This is their third attempt.

Mykhailo, the head of the Unbreakable initiative, is standing near the well. He says that during the month of their stay in Vuhledar, the number of buildings burned down by shelling has increased significantly. In the basement, they have set up showers and a kitchen, painted the walls, installed electricity to charge phones and watch TV, and connected Wi-Fi.

“The point will not save people from guided bombs,” says Mykhailo, “But before, people used to collect water in a barrel outside. And there was a case when they were hit, and there were victims. Now they can go down to the basement and collect water here.”

Volunteer Mykhailo (center) supervises the construction of the point. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteer Mykhailo (center) supervises the construction of the point. Photo: Albina Karman A well drilled by volunteers in Vuhledar. Photo: Albina Karman

A well drilled by volunteers in Vuhledar. Photo: Albina KarmanMykhailo recalls that when the volunteers first came to Vuhledar, the locals were not very happy to see them. Moreover, some of them listened to Russian radio. However, after the locals saw what the volunteers were doing for them, they even brought them flowers.

“We connected them to a TV with Ukrainian news. A month later, they were asking us to turn on these channels,” says the volunteer.

Flowers were given to the volunteers by residents. Photo: Albina Karman

Flowers were given to the volunteers by residents. Photo: Albina KarmanThe TV mentioned by Mykhailo is hanging in the kitchen in front of the table. Volunteers are trying to find the expiration date of condensed milk to make coffee for us. A large circle of people in brightly colored vests is gathering around. After a day of drilling, repairing, and delivering food, they are all tired. But despite this and the constant enemy shelling from the outside, laughter can be heard in Vuhledar’s basement.

This basement seems unlike any other. How such smiling people can be reconciled with lime walls and drilling a well in the basement of a town destroyed by the Russians just a few kilometers from the gray zone?

Volunteers Milan and Serhiy check the shelf life of condensed milk for coffee. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers Milan and Serhiy check the shelf life of condensed milk for coffee. Photo: Albina Karman Vitaliy, a volunteer, was an actor before the war. Photo: Albina Karman

Vitaliy, a volunteer, was an actor before the war. Photo: Albina KarmanIn the evening, locals began to approach the point of invincibility. An older man and woman made themselves some hot tea, but when they saw the camera, they left the kitchen. The volunteers clarify that journalists are not welcome here.

Volunteers Ilya and Vitaliy rest near the showers after extracting water. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers Ilya and Vitaliy rest near the showers after extracting water. Photo: Albina KarmanA scared dog hides at the feet of one of the men – four-legged animals also have a home here. In the evening, it is cozy here. For a moment, the atmosphere resembles a group of friends on vacation until another explosion comes from above.

Volunteer Ilya and a dog from Ugledar. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteer Ilya and a dog from Ugledar. Photo: Albina Karman Volunteers Serhiy and Marat. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers Serhiy and Marat. Photo: Albina KarmanIt’s getting dark outside. Some volunteers are leaving Vuhledar, so it’s time to go.

They start hugging each other goodbye and joking about falafel, which they haven’t seen for a month. They hope to eat it together somewhere in a safer city.

Hugs before leaving. Photo: Albina Karman

Hugs before leaving. Photo: Albina KarmanMykhailo says that their pink buses are always in a visible place on the street. This is so that the enemy can see that there are civilians here.

“If they bomb us, they don’t want to say that the military were here,” says Mykhailo.

He also constantly films and posts on social media all the work inside the checkpoint.

“So that they can see that there are civilians here,” he adds.

The door of the Unbreakable group’s bus. Photo: Albina Karman

The door of the Unbreakable group’s bus. Photo: Albina Karman The pink bus of the Unbreakable group on the way to Vuhledar. In the background is the smoke from the shelling. Photo: Albina Karman

The pink bus of the Unbreakable group on the way to Vuhledar. In the background is the smoke from the shelling. Photo: Albina KarmanAccording to him, within a few days of their arrival, the Russians posted videos of the Unbreakable in their chats. They shared almost everything Mykhailo recorded and posted on social media. Except for the videos with Ukrainian songs playing in the background.

Before leaving, explosions started in the city again. Photo: Albina Karman

Before leaving, explosions started in the city again. Photo: Albina Karman“Andriy will get behind the wheel, start the car, and then everyone will quickly get out and leave,” Valeriy holds the volunteers at the door and gives them instructions as explosions are heard in the city again.

Navigating the same pits, volunteer Andriy asks several times, remembering the Unbreakable group: “Why are they risking themselves so much?”

“They are not just risking themselves. They seem to see this help as a deep meaning of their lives, at least for now,” I answer.

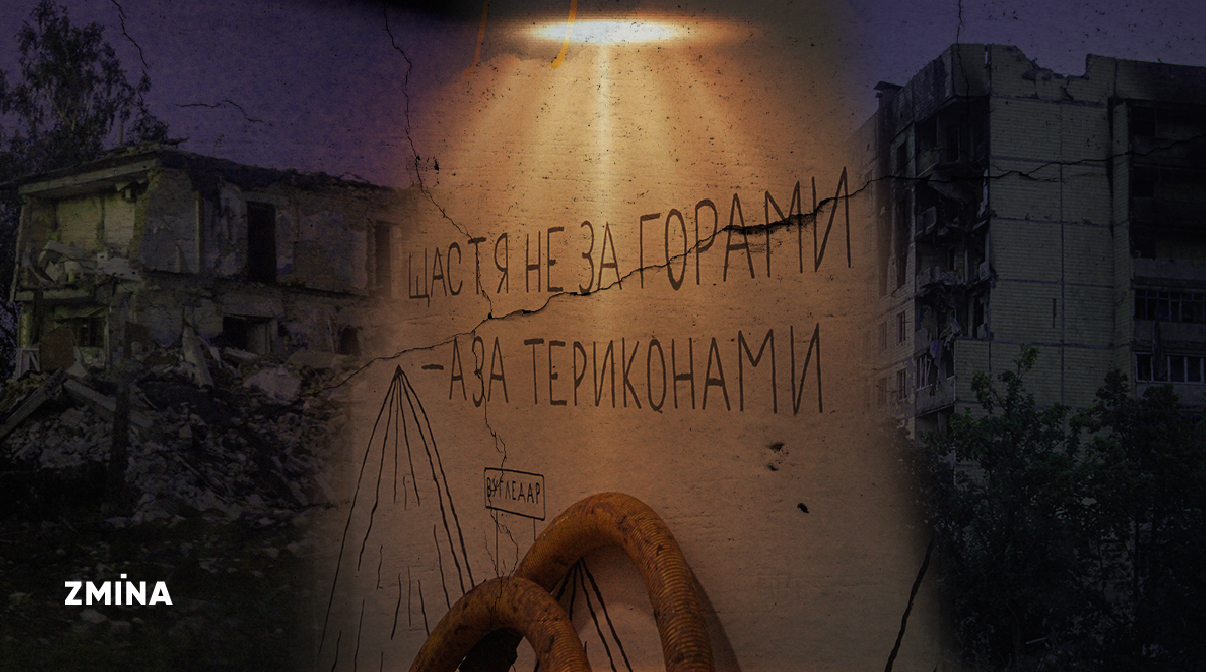

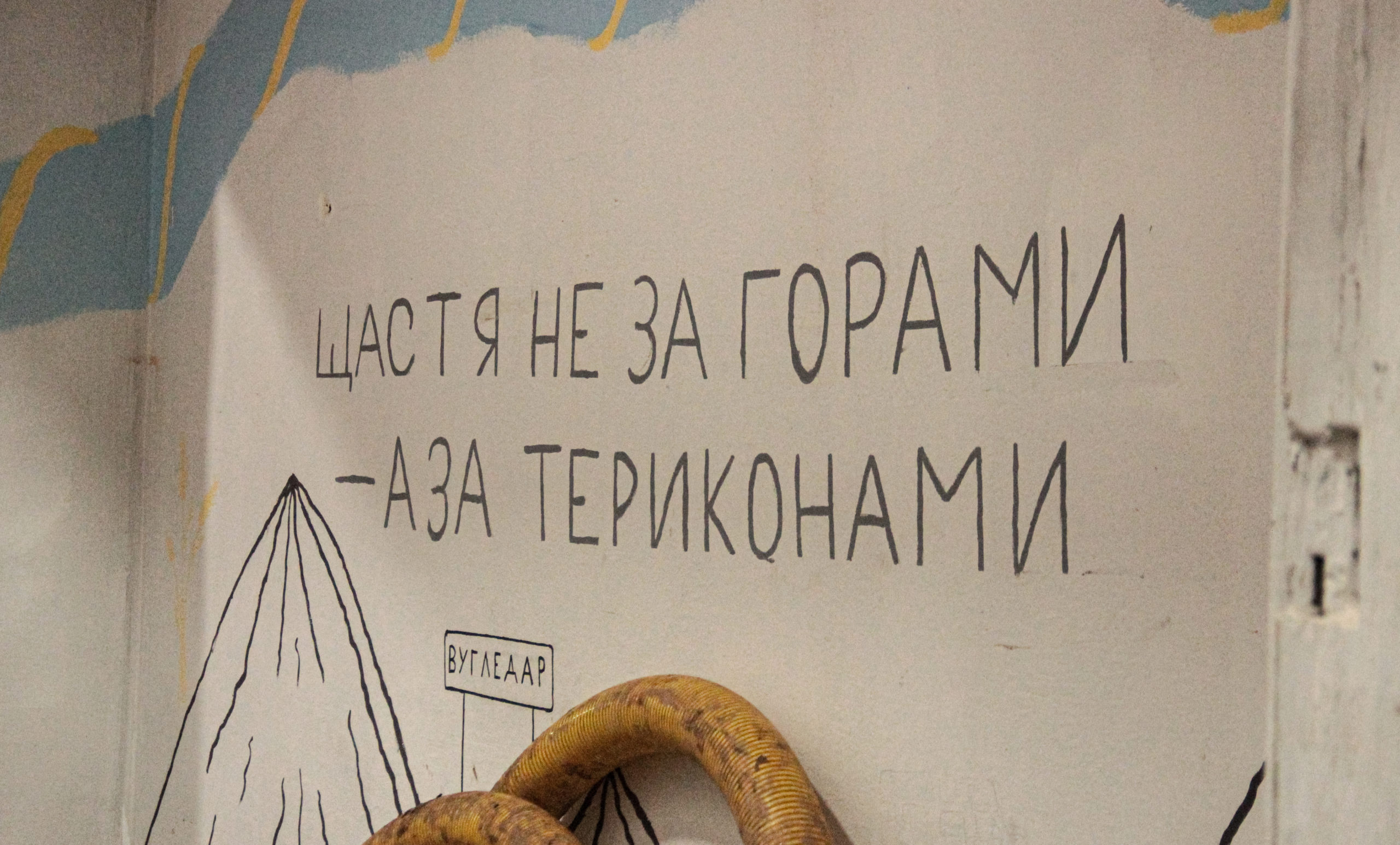

Volunteers painted a mural on the basement wall. Photo: Albina Karman

Volunteers painted a mural on the basement wall. Photo: Albina KarmanToday, the invincibility point has been fully completed, and the volunteers of Unbreakable have returned home to Irpin.

“From hatred, from disrespect, we came to the point where people in Vuhledar were crying when we left. This is the fight for people’s hearts,” Mykhailo says with a smile.

They plan to build the next point of invincibility in another frontline city.