How Ukraine passes judgment on violations of the laws and customs of war?

Over the past two years, Ukrainian judges have convicted at least 101 people for violating the laws and customs of war. Among them are Russian officials, soldiers, and officers of the Russian army who robbed civilians in Ukraine, shelled residential buildings, abducted, tortured, and killed residents of the occupied territories, as well as Ukrainian citizens who helped the Russians commit violence during the occupation.

More than 80 trials in these cases were held in absentia. At least three convicts were released from prison and exchanged for Ukrainian prisoners of war, and some suspects were sent for exchange even before the investigation was completed.

Today, lawyers say it is possible to examine these cases comprehensively and analyze their entire path, from the beginning of the investigation to the announcement of the verdict. This makes it possible to assess the prospects for such proceedings in the future and their role in establishing justice for the crimes of this war.

ZMINA analyzed how Ukraine tries war criminals and what challenges it faces.

Crimes real, verdicts in absentia

To date, Ukrainian courts have announced verdicts against at least 101 people in cases of war crimes against Ukraine and its people. The latest verdict on the violation of the laws and customs of war was announced by the Chernihiv District Court on March 25.

The convict is a soldier of the Russian Armed Forces, Orlan Dorzhu. As the investigation established, on March 5, 2022, Dorzhu and his unit entered the village of Viktorivka, Chernihiv region. On the same day, Dorzhu and other soldiers broke into a private house. There, a family hid in the basement – two adults and two young children.

According to the case file, the convict threw a metal pan into the basement to scare the people inside. After that, he ordered everyone to go outside. Otherwise, he threatened to throw a real grenade at them.

The Russian military searched the family. After that, Dorzhu, according to law enforcement materials, forced the civilians back into the basement and locked the door from the outside.

According to the Chernihiv prosecutor’s office, the basement had no ventilation or access to fresh air. The family was locked in complete darkness, unsanitary conditions, without food, and the temperature was near zero. Only after eight hours of such detention did the victims manage to get out of the basement on their own. They have never seen the military officer who locked them there again.

Dorzhu was sentenced to 12 years in prison for the ill-treatment of civilians during the occupation. It is the largest category of crimes for which verdicts have been handed down in war crimes cases so far. At the same time, almost all of these decisions were made in absentia. Dorzhu was also sentenced in absentia.

More than 80% of court cases involving violations of the laws and customs of war are currently held in absentia.

Trials in absentia are an accepted practice in the international judicial system. Such trials allow justice to be served even when criminals cannot be immediately reached by legal means.

In Ukraine, this option was added to the legislation after the Russian invasion of 2014. The Sloviansk City District Court handed down the first sentence in absentia in November 2015. Back then, a former Horlivka police officer who had sided with the Russians and headed the seized local Interior Ministry department unit was sentenced to nine years in prison with confiscation of property. He was accused of participating in a terrorist organization.

The first sentence in absentia for war crimes was announced in Ukraine after the full-scale invasion of 2022. It went to 23-year-old Serhiy Shtainer.

He is also the first convicted war criminal to be identified by journalists. Later, the Radio Liberty journalist who conducted the investigation testified in court.

Like most war criminals, Sergei Shtainer was found guilty of cruelty to civilians in the occupied territory. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, he was a lieutenant and commanded a unit. At least since March 9, 2022, the convict and his subordinates were in the village of Lukianivka, Kyiv region. He gave orders to rob residents. In particular, on Shtainer’s orders, the Russians stole a phone, a gasoline generator, and ten concrete slabs from one of the victims and crushed his car with the military vehicle. In addition, according to the prosecutor’s office, Shtainer gave orders to shoot civilian vehicles.

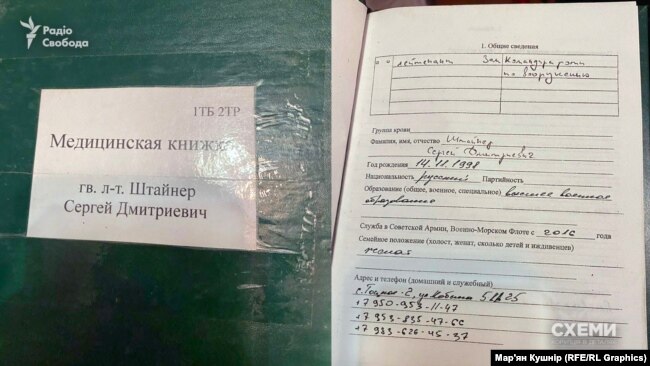

When the Russian military fled Lukianivka following the Ukrainian counteroffensive, they left much evidence of their presence in the village. For example, the Ukrainian army found Steiner’s medical book in one of the abandoned tanks. They showed it to Radio Liberty journalists, who identified the perpetrator.

Military technical documents and medical records of Serhiy Shtainer, deputy weapons unit commander. Photo: Marian Kushnir, Radio Liberty

Military technical documents and medical records of Serhiy Shtainer, deputy weapons unit commander. Photo: Marian Kushnir, Radio LibertySubsequently, victims and witnesses of the Russians’ actions in Lukianivka identified Shtainer from a photo. The Russian’s lawyer asked for his acquittal, as the court failed to hear the defendant’s testimony.

“Given the evidence collected and the information that became known during the court investigation, I conclude that my client’s guilt has not been proven. There is no direct evidence that he committed the crime he is charged with. There are no direct testimonies from either the victim or witnesses that would point to the person in question,” the lawyer emphasized during the trial.

The defense lawyers of accused war criminals have resorted to this position on numerous occasions, namely in the case of junior sergeant Oleksandr Karpov, who was accused of shooting a civilian car in the Chernihiv region.

According to the text of the verdict, on the evening of February 26, the Russian, along with other Russian military, ordered a civilian car with four people in it to stop. The driver stopped the car, but at that moment, one of the Russians began shooting at the vehicle. As a result, a passenger sitting in the front seat was killed, the driver and another passenger were injured. The victims later identified the soldier from a photo.

According to the victims, at the time of the crime, it was already getting dark; a large light on the roof of the armored personnel carrier was shining toward the car, and a soldier was standing in front of the vehicle, shooting at the car. Because of this, the defense counsel insisted that his client’s guilt was not proven: the victims could not see the offender well and could make a mistake in identification.

The case file, however, states that law enforcement officers were conducting an investigative experiment. A ZIL truck with a roof light was parked at the spot where the victims said the APC was. A car similar to the victims’ car was placed 15 meters away, and with the help of witnesses, they checked whether the victims could recognize the attacker from that distance. The experiment confirmed that seeing and identifying a person’s face on a combat vehicle is possible under such conditions. In addition, the case file contains information about the accused’s telephone connections. This data shows Karpov could have been near the crime scene in February and March 2022.

At the same time, some decisions do not provide enough details to unequivocally establish the suspect’s guilt.

Attention to detail

Alina Pavliuk, a lawyer at ULAG, a Ukrainian legal advisory group, says the fact that the proceedings are held in absentia does not mean they will be ineffective by default.

She cites the example of the MH-17 case, which the District Court of The Hague heard: this case was also held in absentia, but the process was very transparent, systematic, and had a clear logic of evidence and prosecution.

Four defendants were in the case, but this did not prevent the court from paying attention to the significance of each person’s actions in the crime. Thus, the judges acquitted one of the defendants, Oleg Pulatov. The investigation noted that the man was involved in transporting the Buk missile system to Ukraine, which was used to shoot down the passenger plane. However, the court did not find evidence in the case file that Pulatov was directly involved in the launch of the missile that hit Boeing.

Pavliuk emphasizes that Ukrainian courts should follow the same principle: to establish the role of each person in the commission of a crime, especially when it is a case in absentia with several defendants. To do this, it is necessary, in particular, to analyze in detail all the circumstances of the case and provide the most comprehensive evidence of the guilt of all the defendants individually.

Ukrainian courts have heard more than one war crimes case involving two to fifteen defendants. Such mass trials help keep law enforcement and judicial resources focused, as otherwise they would have to consider, for example, 15 cases of the same crime.

This approach is also essential for victims and witnesses in war crimes cases.

“Let’s imagine it would be 15 separate proceedings about the same situation. And the affected person would have to attend court hearings in each of them,” the ULAG expert notes.

At the same time, she said, in cases where there is more than one defendant, the degree of proof of each defendant’s responsibility is sometimes insufficient.

“Often, when we see a large number of people in a verdict, it is difficult to understand who exactly committed what crimes and what the limits of their responsibility for committing a particular element of the crime are,” the lawyer adds.

For example, in March of this year, the Chernihiv District Court of Chernihiv Oblast passed the most massive war crimes sentence to date. Fifteen Russian soldiers were found guilty of illegally detaining civilians in the village of Yahidne in the basement of a school and treating them inhumanely.

People in the school basement in Yahidne. Photo: Olha Meniailo

People in the school basement in Yahidne. Photo: Olha MeniailoThe text of the verdict describes in detail the actions of one of the Russian military defendants. He was, in particular, directly involved in three facts of illegal detention of civilians and their escort to the basement of a village school. The court found that that person searched people, forced them to strip naked in the cold, searched for “suspicious” tattoos, locked the victims in the basement of a private house, and threatened them with weapons. At the same time, he performed most of his actions “together with other members of the Russian Federation armed forces,” the court said.

One of the defendants, according to the verdict, punched a civilian man in the head. Another Russian soldier tried to rape one of the women held in the basement. However, the degree of involvement of the other defendants in the commission of the crime, according to the verdict, is rather vague.

Thus, the actions of most of the defendants, in this case, are described in the same way: “…acting intentionally, under the threat of firearms, they unlawfully detained (imprisoned) the said civilians for their further unlawful detention in the basement of the school, forcibly took the victims from the basement to the yard of the said household” or “together with other unidentified servicemen of the armed forces of the Russian Federation, under escort, took the victims and forcibly placed them in the basement” of the school in the village of Yahidne.

In addition, the court found that all the defendants participated in guarding the entrance to the school basement and, accordingly, created conditions for the illegal detention of these people. All 15 defendants were also found guilty of using civilians as human shields.

At the same time, such wording makes it difficult to establish what precisely the defendants did as part of the crime and what degree of responsibility each deserves. In the end, all the convicts – the one who beat the civilian, the one who forced them to undress in the cold, the one who wanted to rape the detainee, and the one who detained the civilians and escorted them to the basement – received the same sentence of 12 years in prison.

In the two years since the war crime in Yahidne, Ukrainian courts have sentenced 21 Russian soldiers involved in the abuse of civilians in the village of Yahidne in Chernihiv Oblast. All of them are direct perpetrators.

It is a common feature of most criminal proceedings for war crimes in Ukraine, Pavliuk said.

“We see the intention to bring to justice the direct perpetrator of the crime. However, the importance of these cases is that not only the perpetrators must be held accountable. It is necessary to prove the role of top management in these crimes,” emphasizes the lawyer.

According to the procedure

Justice in absentia in Ukraine today also has several procedural problems. For example, there is always a risk that the court will disregard the defendant’s rights and convict him or her unfairly during the trial in absentia. Therefore, international judicial practice requires additional guarantees that the defendant’s right to a fair trial will be fully respected during the trial in absentia.

A trial in absentia is possible only if the accused person is aware of the criminal case against him or her, can familiarize himself or herself with the materials, and has been notified of the stages of the proceedings.

According to Ukrainian procedural rules, investigative authorities must send a person a notice of the opening of proceedings, the start of an investigation, suspicion, or court hearings in cases against them. These notifications are sent in several ways, and the defendant is expected to see at least one.

Ukrainian law enforcement and judicial authorities mostly fully comply with legal requirements. However, lawyers emphasize that this does not always guarantee that the defendant or suspect is aware of his or her status.

In particular, law enforcement officers should send notices to the suspects’ residential addresses. However, it is mainly impossible to do so, as those accused of war crimes are in Russia or the occupied territories of Ukraine.

Another way is to publish suspicions and summonses in print media, such as the Uryadovyi Kurier, the Judiciary of Ukraine portal, and the website of the Prosecutor General’s Office.

These methods of notification are also ineffective, lawyers say.

“How high is the probability that a person in the occupied territory or Russia can, in principle, have access to these sites? After all, as far as we know, access to Ukrainian Internet resources in these territories is blocked,” emphasizes lawyer Alina Pavliuk.

Another legislative problem for trials in absentia in Ukraine is the imperfection of the appeal procedure. Since the investigation and prosecution occur under special conditions, Pavliuk said it should also be possible to appeal the verdict under a special procedure.

“The European practice of the right to a fair trial requires additional guarantees that a convicted person if he or she appears and wishes to appear in court in this case, will have a real opportunity to review it, appeal against the decisions made, and present his or her side to the court,” the lawyer adds.

If a convicted person appears in Ukraine, they will be arrested immediately, and the sentence will enter into force. Defenders of those convicted in absentia appeal to the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court as a cassation instance in the general procedure. However, to date, during the entire ten years of Russia’s armed aggression, only one case has reached the Supreme Court – that of Crimean military commissar Oleksandr Kabashny, who was sentenced to eight years in prison for conducting forced conscription of civilians in occupied Crimea for military service in the Russian army.

Oleksandr Kabashny

Oleksandr KabashnyThe defense, both in the Court of Appeal and in the Supreme Court, insisted that the prosecution had failed to prove the element of coercion in Kabashny’s actions: the investigation had not provided factual evidence that the defendant had directly used physical force, psychological violence, blackmail or threats to force Crimeans to serve in the Russian army. The court rejected these statements and determined that coercion cannot only be directly expressed in threats or violence. After all, Kabashny stated in the Russian media that “evaders” [of serving in the Russian military] would be searched for and imprisoned. According to the Supreme Court, it can also be considered coercion.

Kabashny’s lawyer in the Supreme Court also pointed out the lack of a special procedure for appealing decisions. The judges responded that such a procedure did exist, but Pavliuk emphasized that one should try to prove one’s right to use it.

In general, the Supreme Court’s decisions do not only confirm or appeal verdicts. This body also analyzes judicial statistics and summarizes judicial practice. Thus, from the first decision in the war crimes case, lawyers expected explanations and comments on the practice of qualifying international crimes, the specifics of the trial of such cases, and, ultimately, their appeal.

“However, the judges only raised a number of procedural issues in their decision. Unfortunately, we did not see a substantive decision that could change the current approaches to dealing with war crimes,” Pavliuk said.

A sentence is not the end

Legislative and procedural shortcomings in war crimes proceedings may affect the fate of these verdicts and the actual prosecution of the perpetrators.

A sentence in absentia means a person will be detained as soon as they are found, even if they are in another state’s territory. However, for other countries to detain the offender, they must be put on the international wanted list.

But, for example, Interpol, the leading international criminal police organization, often refuses to put on its wanted list those people whom Ukraine suspects of national security or war crimes. The international agency may regard such cases as political rather than criminal.

“During the war, Interpol has shown itself to be an organization that does not always meet us halfway, an organization that plays politics rather than performs the functions for which it was founded,” said Interior Minister Ihor Klymenko.

However, even when criminals are on the international wanted list, this does not guarantee they will be brought to justice or handed to Ukraine. For example, in late 2023, after Finnish law enforcement detained Jan Petrovsky, whom Ukrainian law enforcement suspects of terrorism, Ukraine asked Finland to extradite him. However, the Finnish Supreme Court refused, citing the ECtHR’s findings of inadequate detention conditions in Ukrainian prisons.

Instead, Finland has launched its preliminary investigation into Petrovsky’s alleged war crimes under universal jurisdiction. This convenient legal tool allows any country that has adopted the relevant legislation to launch an investigation into international crimes, even if they did not occur on its territory or with its citizens. Today, at least 24 countries around the world are conducting their investigations into war crimes in Ukraine.

However, no matter how many other countries join this process, Ukrainian law enforcement will investigate most crimes, and Ukrainian courts will pass sentences for these criminals.

Not sprint, but a marathon

As of February 23, 2024, Ukrainian investigators had referred 246 cases to the judiciary under Article 438—violation of the laws and customs of war. Judges have handed down more than 60 verdicts since then.

“Such a mass of proceedings in absentia sent to the court during the two years of the full-scale invasion seems to be an attempt to show statistics rather than an attempt to ensure justice,” emphasizes lawyer Alina Pavliuk.

She emphasizes that according to the Criminal Procedure Code of Ukraine, war crimes have no statute of limitations or time limits for their investigation. Therefore, investigators can work on collecting evidence and establishing the truth as long as a particular case requires. High-quality documentation and analysis of all case materials at the investigation stage will guarantee the success of this case not only in court and at the appeal stage in Ukraine but also in the event of possible repeated reviews of these cases in the future, including in international courts.

The quality and quantity of the information collected, approaches to working with this evidence and to the documentation process in general, the qualification of crimes, cooperation between law enforcement and judicial authorities in the country – all of this, among other things, affects how Ukraine will prove the hierarchy of those responsible for war crimes, in particular the involvement of the top leadership of the Russian Federation, Pavliuk adds.

The lawyer emphasizes that the problems with investigating war crimes and bringing their perpetrators to justice are not new to Ukraine: they arose in 2014 when Russia seized Crimea and parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine.

“In my opinion, we are still in the same situation with these investigations and lawsuits that we were in 10 years ago,” the lawyer says.

The Ukrainian law enforcement system still has problems processing and preserving different types of evidence. In particular, the lawyer emphasizes that standards for working with electronic evidence must be regulated. She says that information from open sources is often used in investigations only as a background, although such evidence can be pretty significant. In addition, just like ten years ago, Ukrainian courts do not accept intelligence as evidence, Pavliuk adds.

These problems require a comprehensive approach and must be addressed primarily at the legislative level, emphasizes the ULAG lawyer.

“There is a lot of homework. But we need to start changing approaches to these criminal proceedings from the Criminal Procedure Code: to develop relevant ways to investigate such crimes, to take into account the challenges of today and international standards of justice,” she noted.

But at the same time, trials of war criminals must take place, Pavliuk notes.

“This is a form of communication with victims. It is an opportunity to show them that investigations are ongoing, cases are moving forward, and they are remembered,” the lawyer adds.

Opinion polls regularly demonstrate the thirst of Ukrainian society for the punishment of war criminals. Thus, according to a recent study by the Rating sociological group, 47% of respondents see justice in the context of the war as punishing war criminals. At the same time, for one-third of respondents, justice means establishing the truth about all the events of the Russian invasion.

It is also important not to forget that the invasion did not begin in 2022, experts emphasize. The current events are directly related to the occupation of Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions in 2014. Moreover, the war crimes that residents of almost all of Ukraine faced two years ago have been committed by Russians in the occupied territories for years. Therefore, investigations and court cases should be based on the overall picture of the ten-year war, Pavliuk emphasizes. It will ultimately help to establish the hierarchy of those responsible for international crimes and bring them to justice, including the top leadership of the Russian Federation.