From Kupiansk to Melitopol: the Russian system of torture in illegal detention centers

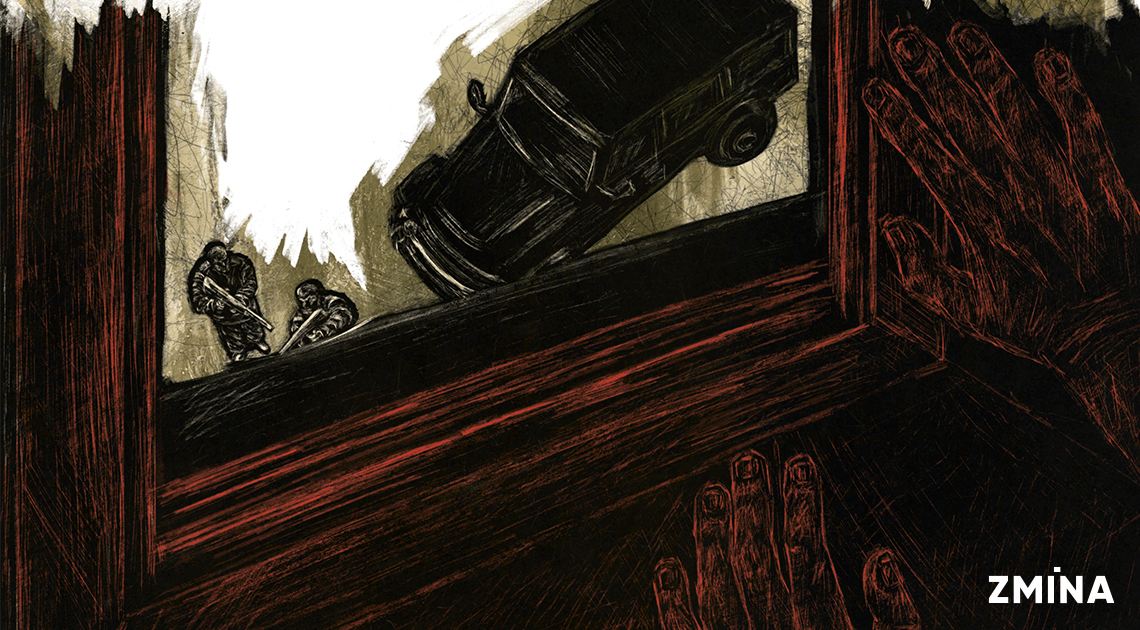

He was kidnapped from his home at gunpoint, put in a bag over his head, set in a car, and taken to an unknown destination. He was kept in a crowded cell without fresh air. They did not give him enough food and water and did not provide him with medical treatment.

They took him for interrogation and tried to find out the names of local soldiers, activists, and volunteers. They beat him with their fists, feet, truncheons, and rifle butts. They connected terminals to his fingers, chest, and genitals and turned on the electricity. They threatened him with deportation, mutilation, rape, and execution.

It is a typical scenario for many civilians illegally abducted by the Russian military in Kupiansk, Kherson, Nova Kakhovka, Melitopol, Berdiansk, and other occupied settlements.

The descriptions of the experience are sometimes repeated to the smallest detail: the same detentions, torture and interrogations, similar conditions of detention, and even rules of conduct in prison.

Such behavior towards the residents of the occupied territories is part of a global policy of terrorizing the civilian population of Ukraine, human rights activists say. It may also be evidence of the systematic and large-scale nature of Russian crimes – elements that constitute crimes against humanity, in particular.

ZMINA analysts reviewed the testimonies of victims who were illegally detained by the Russians in various places in the occupied territories between April 2022 and March 2023. Here are the main points from the analytical report, “Illegal Detention, Torture and Ill-treatment of the Civilian Population of Ukraine: Similarities in the Practices of Committing Crimes in the Regions Occupied by Russia in 2022.”

Who are the Russians looking for in the occupation, and how?

With the help of the military, the Russian authorities established a “security regime” in the occupied territories: document checks on the streets, “filtration” procedures, and searches in government agencies, private businesses, and residential buildings.

“We had scheduled [inspections]. The Russians – the Rosgvardia – were conducting searches of the population. They usually looked for guerrillas and anyone who was against the Russian Federation. To intimidate the population,“ said the interviewed victim.

First and foremost, the Russian military is looking for current and former law enforcement officers and military personnel in the occupation, especially those who served in the Anti-Terrorist Operation/Joint Forces Operation. They also perceive local government representatives, volunteers, activists, cultural workers, educators, and any civilians who have ever expressed their support for Ukraine as a threat.

Russians often use documents they seized from administrative buildings to identify these people. These documents include lists of people liable for military service or lists of veterans who were supposed to receive land plots.

Russian security forces are also looking for people for photos and videos of resistance actions at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and sometimes even accuse detainees of having photos from the Euromaidan era.

In the occupied territories, people can be detained on the street, stopped for document checks, and taken to a detention center. Often, the Russians do not need reasons or evidence for such actions. They have repeatedly constructed accusations based on their guesses and assumptions.

For example, one of the interviewed victims was detained by the Russians because they found a photo of his nephew with the symbols of the Right Sector. At the same time, the nephew had left the country before February 24, 2022.

During the search for another victim, Russians found a scarf from the Metalist football club. The man was accused of participating in the events in Odesa on May 2, 2014, as the team was scheduled to play against the local Chornomorets in Odesa that day.

At the same time, the primary source of evidence about the local population for the Russians is information from other civilians. It is important to note that this is not only about denunciations, which the Russians encourage people to do in every way possible. It is often information obtained under torture from those who were detained earlier.

For example, the Russians could have set conditions for the detainees.

“If you want to get out, you have to turn in ten drug addicts, ten soldiers. They gave the guys a piece of paper and a pencil to write with,” recalls one of the respondents.

Human rights activists emphasize that the Russian administration is trying to destroy established social ties in communities in this way. People who have been kept in one place sometimes tend to be distrustful even of each other.

In addition, quite often, victims know for sure who passed information about them to Russian units. As a result, they break off old social ties, stop communicating with former friends and acquaintances, or try to move to a different settlement.

The conditions were similar in Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Kharkiv regions

ZMINA human rights activists investigated, in particular, the torture chambers that the Russians set up in temporary detention centers in Kherson and Kupiansk, in penal colony No. 66 in Berdiansk, as well as in police stations in Nova Kakhovka and Tokmak.

Even though these places have the necessary infrastructure, the Russians have created inhumane conditions there.

Victims often talk about overcrowded cells: a four-person cell, for example, could hold about 20 people. Because of this, many detained civilians had to sleep on the floor, sometimes even without mattresses. Moreover, ZMINA documenters recorded cases where detainees could only stand in their cells.

All of the interviewees whose testimonies were analyzed in the report stated that they were deprived of privacy during the entire period of detention. There were no toilets in some of the cells where the interviewees were held. They were usually given plastic bottles, buckets, or even pots for their natural needs. These containers were kept in the same room as the hostages, but they were not always allowed to take them out.

Most respondents reported problems with drinking water and poor nutrition: they were fed irregularly, and the food was mostly stale. Some victims received food only in parcels from their relatives.

However, for some detainees, the Russians did not accept parcels at all. It could have been a “punishment” for violating the rules established by the occupiers or an attempt to hide the fact that they were holding a person.

Many victims say that the Russians restricted the access of fresh air to the cell.

“I was released on May 28, but there (in the illegal detention facility – Ed.) there was still heating around the clock – two large thick pipes. It was simply impossible to breathe there. It was like a bathhouse from which you cannot leave,“ says the victim interviewed, who was held in penal colony No. 66 in Berdiansk.

Russian military and security forces also use access to fresh air as an additional element of pressure on detainees. For example, the human rights defenders received a number of testimonies of guards or convoys deliberately closing the “feeding trough” – a window for food delivery – in the cell door. This window was often the only place through which air entered the room, so when it was closed, it became very difficult to breathe in the cell, according to the victims.

In general, “punishment” through deteriorating detention conditions is common among Russians. The vast majority of respondents who were held in occupation in different regions of Ukraine reported such cases.

Victims from Nova Kakhovka, Kupiansk, or Berdiansk describe very similar “rules of conduct” in detention, the way guards communicate with them, and the procedures for escorting them. At the same time, they resemble the procedures of penitentiary institutions in the Russian Federation.

For example, when the cell door is opened, all detainees must face the wall, lean on it with their hands, and spread their legs. Their heads and eyes should be kept down at all times.

Usually, a person taken for interrogation is put in a hat or a bag, sometimes wrapped with tape. They are led with their hands tied in a semi-bent position.

“You leave the cell, face towards the wall. They immediately put a bag on your head and wrap it with tape. They put your hands back, and handcuffs are put on. And two people hold you by the arms and pull you out in a “swallow” position,” said the victim from Kupiansk.

ZMINA also recorded numerous cases when escorts deliberately created situations for detainees to be injured. On the way to interrogation, a person with a bag on his head could be pushed into a wall or made to stumble on the stairs.

Similar patterns of interrogation and torture

Human rights activists note that most of those interviewed had suffered torture: only “valuable” prisoners or those who were too ill were not abused.

Thus, the human rights defenders documented several cases when the occupiers abducted and detained women with cancer. They were hardly ever subjected to physical violence, but they were psychologically abused and not allowed to take the necessary medications regularly.

Other detainees in different cities in the occupied territories were tortured using similar methods. Even specific elements of torture were repeated.

Most often, people were beaten with their hands, feet, rubber truncheons, wooden bats, and rifle butts. Sometimes, they used whatever was at hand, such as books or plastic water bottles.

The detainees also spoke about specific long-term beatings: they did not pose a direct threat to life, but due to the constant impact, it was impossible to endure them, the interviewees recalled.

“They took an ordinary plastic water pipe and slammed you with it. At first, it seems like nothing, but when they do this for 10 minutes, you are ready to die there,” says one of the victims.

In all occupied territories, detainees were subjected to electric shocks. Victims could be beaten with stun guns during searches, detentions, or in cells. However, the worst torture was electric shocks during interrogations. Most of the respondents recall this as the worst experience during their detention.

“He brought me there. He said: “Sit down on the floor, lean on the wall with your back and legs forward.” They took off my slippers and put terminals on my fingers. He said: “Tell me: police, Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), ATO – who do you know?” And he started to shock me,” recalls the victim from Melitopol.

To increase the suffering of the detainees, the terminals through which the current was supplied were connected to the most sensitive parts of the body: fingers, ears, nipples, and genitals.

The victims note that the occupiers took breaks in the torture so that the person did not faint and the sensitivity of the damaged parts of the body was partially restored. In addition, the torture was briefly stopped so that the victim realized his or her situation and became more “cooperative,” the victims recounted the words of the Russians.

The military personnel who tortured the interviewees often alternated between types of torture to inflict greater suffering. For example, during a four-hour interrogation, one of the victims was hit on the back of the head with a water bottle, strangled with a cable, a bag was put over her head, and her mouth and nose were clamped, she was threatened with electric shock, a gun was held to her head, and a gun was fired nearby.

“It was probably on the second or third blow that I started to feel that something was [wrong] with my head. It must have been smashed because there was a lot of pain, and my eyes were all white. I started to feel nauseous and dizzy. I fainted briefly. Then they started doing something else,” the woman recalls.

All interviewees reported constant psychological pressure on them and other detainees. For example, ZMINA documenters have repeatedly recorded cases of “paired” interrogations when relatives or close friends were detained, interrogated, or tortured at the same time. Victims were constantly intimidated and threatened with death or injury. Cases of mock executions were also common.

“They beat me on purpose in front of her [the wife]. Then they took her to another room, and they shot me twice with a gun near my ear. They told her that was it – I was shot,” one of the victims recounts.

Human rights activists emphasize that such a simulation of a murder involves the risk of an unplanned shot and thus directly threatens the victim’s life.

In general, ZMINA analysts unequivocally assess most of the documented cases as torture: the Russian military, security forces, and their subordinates deliberately inflicted severe suffering on the detainees.

Typical executors

Victims from Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, and Kharkiv regions noted that detentions and interrogations were usually led by representatives of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). They were often dressed in civilian clothes but had elements of military equipment, such as shoes, and did not show their faces. To do this, they either put on balaclavas themselves, blindfolded the victims, or both.

“The FSB is engaged in detaining people, collecting information, and interrogating them. They are always in civilian clothes, driving cars without license plates – just a black plate,” said a respondent from Kherson.

In addition to the FSB, interrogations and so-called investigative actions were conducted by military personnel who called themselves representatives of the so-called Luhansk People’s Republic and Donetsk People’s Republic armed groups or police officers. Sometimes, they only psychologically “prepared” the detainee for a meeting with the FSB.

“For six or seven hours, various so-called ‘representatives of the newly created police’ came into the room. Each one of them told me a desperate story about how poor they were, how they were starving, how they were not given money. And how they went to work for Russia to save people, and so on,” recalls one of the victims.

Guards and escorts to illegal detention facilities were often recruited from the local population. Sometimes, these were people who had previously served sentences for criminal offenses. They are well aware of prison culture and use the worst practices in their treatment of civilian detainees.

Some respondents spoke about the “training” of locals who agreed to work for the enemy in such torture chambers. After that, the detention regime usually became stricter: communication between cells was prohibited, parcels from relatives were checked more thoroughly, and cell searches were more frequent.

According to the researchers, the Russians and their subordinates coordinated their actions not only at the level of one place of detention but also between different such facilities. Thus, there were cases when detainees were transported to a place of detention in another locality, and the guards were informed of the reasons for their detention. In some cases, the detainees were labeled as “political” or accused of assisting the resistance movement or collaborating with the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Then, such a person was treated more harshly in the new place.

Such a system of torture chambers is part of the general policy of terror in the occupied territories, human rights activists emphasize. Usually, such places operate openly, sometimes even demonstratively. Residents know not only where abducted people are kept but also what is done to them.

The Russian authorities are perpetuating the occupation regime through fear, deliberately destroying social ties in communities and mutual trust between people. Russian forces are also establishing control over communication networks and the internet to cut off ties between people under occupation and the government-controlled territories. It makes it much more difficult to collect evidence of Russian crimes, human rights activists say.

At the same time, some victims are gradually losing faith that the perpetrators will be punished, at least in the near future, so they are less and less willing to testify about their experiences.

Diana Kolodiazhna for Hromadske