Reconciliation never ends: on the challenges of decolonization in South Africa

Decolonization in South Africa didn’t begin with Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990 or the end of apartheid in 1994. It started in the 1850s, when Africans gained access to printing presses and began publishing newspapers in three or four indigenous languages on the same page.

This 170-year project continues today, argues Dr. Hlonipha Mokoena of the University of the Witwatersrand, not in school curricula — which she calls “a lost cause” — but in WhatsApp messages, beadwork, and the everyday decision to speak isiZulu instead of English.

Speaking at the Third International Conference Crimea Global about how former colonies can shed imperial perceptions, Mokoena challenged audiences to rethink where decolonization happens: “The older generation reinforces colonial ideas by telling grandchildren, ‘Learn English — it’s an international language.’ These are the people who need to be decolonized,” she said.

ZMINA has recorded her speech during the conference.

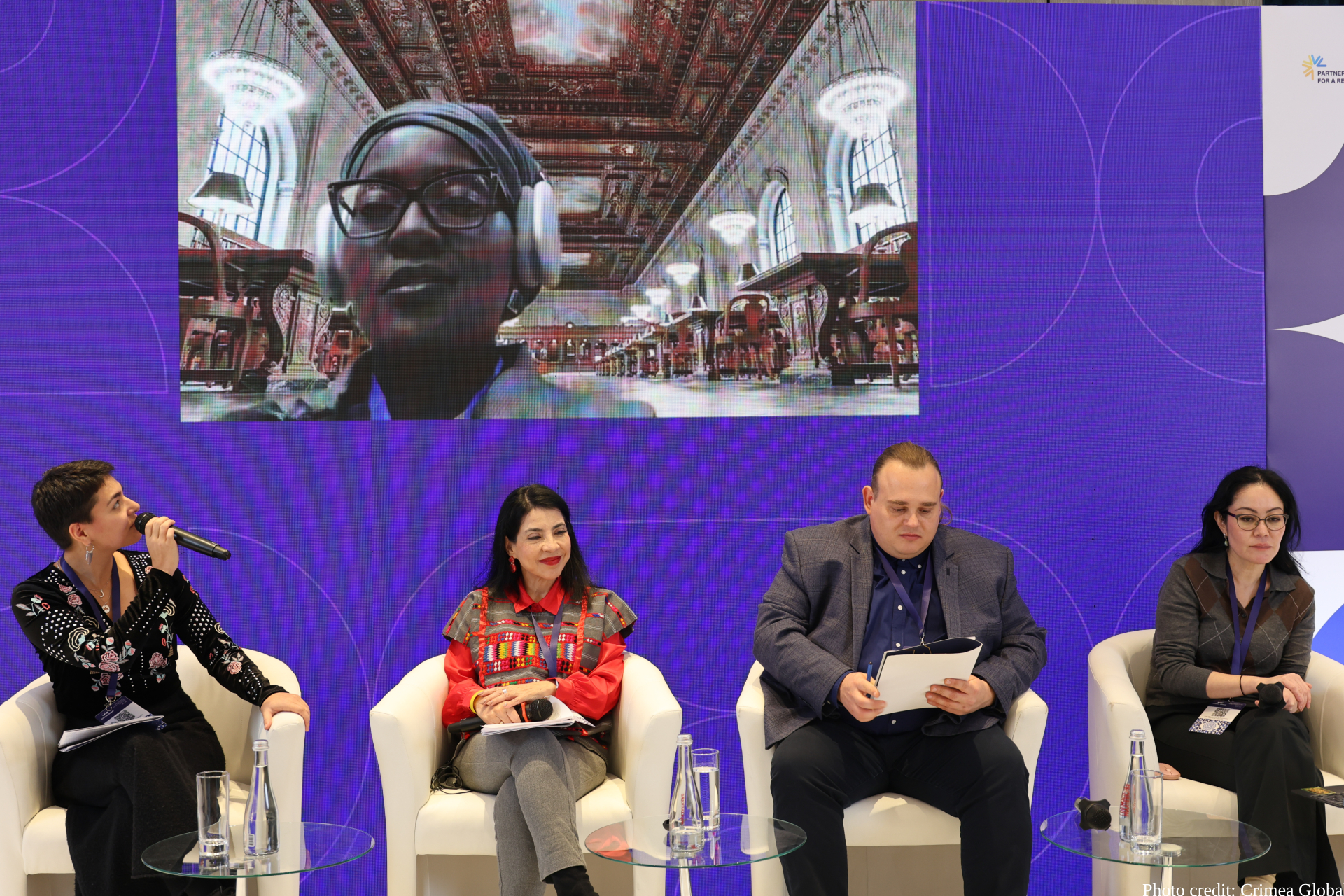

Dr. Hlonipha Mokoena at the panel discussion online

Dr. Hlonipha Mokoena at the panel discussion onlineThe Long History of Decolonization in South Africa

When it comes to South Africa, I like to point out that the project of decolonization began as soon as many Africans gained access to the printing press. Africans who were trained in printing and worked as printers began publishing newspapers and books in indigenous languages in the country in the 1850s and 1860s.

Some of the earliest newspapers in South Africa are actually in indigenous languages. In our case, we cannot say that decolonization began with the end of apartheid in 1994 — this project has been underway since the 1850s. The biggest challenge today is to adopt the same positionalities that many of those early African writers took.

For example, these newspapers didn’t just care about their own languages — they cared about all other local languages. They used to be published in multiple indigenous languages. One page could contain articles in three or four different languages. This was literally the earliest way of thinking about decolonization.

Fast forward to about 2002, after many years of people debating whether there was a readership in indigenous languages, a newspaper was born in my own language, isiZulu.

This newspaper became one of South Africa’s most popular. It proves that not just new technologies make decolonization possible. Some of the oldest technologies — like the printing press — also make decolonization possible, because printing a newspaper is one of the simplest ways to encourage people to think, write, and speak in an indigenous language.

Too often, decolonization projects focus exclusively on formal education — what happens in the classroom. But here is the problem: One way the colonial mindset operates is by creating a contestation over the school curriculum.

For me, as a historian and as a feminist, this is often not a very useful way of fighting or resisting colonialism — picking the same terrain that the colonizer has already picked. The education system is often the most contested space of decolonization. But it is not the only arena we, as decolonial philosophers and thinkers, can choose for this work.

There are so many other aspects of decolonization: music, culture, museums, artifacts, the relearning of indigenous crafts. Our grandparents often tried to teach us how to make things the way our ancestors did — floor coverings, mats, bedspreads, beadwork, and other jewelry.

I’ll give you a personal example. When I met some of your Ukrainian colleagues here in South Africa, I told them I wanted to photograph their beadwork to send to my mother, who loves beadwork and is interested in different styles from around the world. This is one way to take decolonization out of the most volatile space — debates over school curricula.

Many decolonial philosophers focus on debating school curricula. But this is largely a lost cause. The people who control these curricula are often the very ones reinforcing colonial ideas about cultural superiority.

The “International Language” Complex

Take South Africa, for example. English is often held up as an international language. Just that sentence — ‘English is an international language’ — creates inferiority complexes. Speakers of indigenous languages begin to think that they themselves are not ‘international’ simply because their language isn’t called ‘international’.

Even the word “language” itself carries a lot of colonial baggage. You have questions like, “Well, what’s the difference between a language and a dialect?” In South Africa, many languages are actually interrelated. They are like family. But colonialism separated them, telling people: “You speak isiZulu, you speak isiXhosa, you speak Sesotho.” Yet many of these languages are mutually intelligible.

We must create spaces where people can use these languages freely — without worrying whether they’re speaking a “standard,” “international,” “indigenous,” or “threatened” language. All of these terms carry colonial anxieties about how to preserve languages.

From WhatsApp to Archives: Everyday Decolonization

The most “primitive” technologies — newspapers, radio, television, broadcasting — enable decolonization. In South Africa, people use WhatsApp to write to their families in these languages, even though schools insist they must speak English as an “international language.”

Here’s what I’ve discovered in my own work: Most people don’t realize just how much material has been created in local languages by people living a hundred years ago who were already envisioning South Africa’s decolonization. Much of that material is sitting in libraries and archives, simply waiting for somebody to open it and reanimate it.

My first key point: The school or university curriculum is often not the best place to debate decolonization. Why? Because it’s often the older generation who reinforce colonial ideas — telling children, grandchildren, nephews, and nieces: “No, you need to learn English. It’s an international language. Don’t bother with your own language.”

These are the people who need to be decolonized. I know it sounds strange — most of us want the joy of a school curriculum that reflects us, but the older generation often becomes the voice of the colonizer, even though they are indigenous, even though they belong to the same language group as you.

The Aesthetics of Freedom

The second contribution I want to make: For me, there can be no politics without beauty. When we try to imagine who we want to be without the colonial burden, we can’t just imagine ourselves sitting in parliament, having power, or being independent.

Some of you may remember that when our esteemed former president, Nelson Mandela, came out of prison, he was wearing a suit and tie. Soon after he became president, he changed that, adopting a style of shirt that wasn’t even African — it was from Indonesia. This was his way of breaking from the idea that a president must wear a suit and tie. It was a beautiful gesture — acknowledging all the people worldwide who had fought for South Africa’s freedom, while also declaring: you don’t need a suit and tie to be taken seriously or to be decolonial.

There can be no politics without beauty. What are we fighting for? A different world in which people are no longer culturally dependent on the Western world to set the trends.

I often get asked to speak at schools about cultural appropriation. The other side of cultural appropriation is a kind of chauvinistic nativism where people assume that just because you are reclaiming your culture, it means other people are not invited to your culture. I often say to people that there is so much beauty in many of our cultures that there is enough to share with other people.

We have a long history of people from Southeast Asia coming to South Africa — from the Indian subcontinent, whatever term you prefer. On Heritage Day, many people simply pick what to wear from their own ethnic group, but why don’t you celebrate the other people from other parts of the world who have also shaped South Africa?

You can wear a sari on Heritage Day because it is part of our heritage. Beauty is political, and we need to include it in our conversation. We need to get away from the idea that only Western clothing and Western culture are fashionable or professional — that only Western hairstyles and straight hair are fashionable or professional.

All of those issues are political. We need to find the language to speak about a decolonized aesthetic — a cultural sphere where people feel comfortable showing up as themselves, rather than emulating someone else’s culture because they think that culture is ‘winning. Because there’s also the perception that this is a competition and that somebody has to be declared the winner. That is the colonial mindset — that we are competing with other cultures and somebody has to come out as a winner.

We can all win by being beautiful. I love thinking about South African heritage as involving these other cultures that have influenced South Africa, so that we are not just having a discussion about what is “indigenous,” but also a conversation about how indigenous people have taken cultures from somewhere else and made them indigenous, naturalized them, and created new forms of beauty.”

There’s a whole world of beautiful objects we need to discuss when we talk about what it means to think of yourself as decolonized.

Reconciliation Is Never Done

Finally, on reconciliation: Many people think that reconciliation is a once-off process. But, in fact, the experience of South Africa shows that reconciliation is never complete. When you are thinking about reconciling with your former colonizer, you are not thinking about giving them a free pass. This is how some people characterized the Truth and Reconciliation Commission — that people were given a free pass. But that was not really the truth of how the commission was conceived.

You are giving people the opportunity to take responsibility for the crimes they’ve committed against others.

Another point I want to make: Colonialism in one place is colonialism everywhere. The colonial mindset is an infectious disease, and it can affect anybody. In some ways, we all have an interest — those of us who have been oppressed have an interest in solidarity so that we are not always fighting these fights alone.

When we think about reconciliation, South Africa developed a particular model, but it shouldn’t be the only one. This conversation should be going on amongst all people who have been colonized and oppressed, and it should not be thought of as a once-off — “Oh, we have done reconciliation, now let’s get on with life.”

It’s really a continuous process of reevaluating harm, injustice, and the concept of repair. How do you undo the wounds, the suffering, and the pain that people have suffered under the colonial regime?

Dr Hlonipha Mokoena, Associate Professor and Researcher at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa