From Nairobi to the Donbas: Nearly 300 deceived Kenyans trapped on Russian front lines

Russia’s recruitment of foreign fighters from the Global South has become one of the war’s least visible scandals. Since 2022, Moscow has targeted the economically vulnerable across Africa, South Asia, and Latin America — Nepalese promised security work, Kenyans told they would guard facilities, Cubans offered escape from grinding poverty. Instead, they have become expendable infantry in a war they barely understand, while young women from Brazil and African nations labor under exploitative conditions in Russian drone factories.

Moscow’s recruitment network doesn’t stop at fighters: Young women from African nations and Brazil are being brought to Tatarstan, told they will assemble drones, only to face conditions that human rights experts say constitute trafficking.

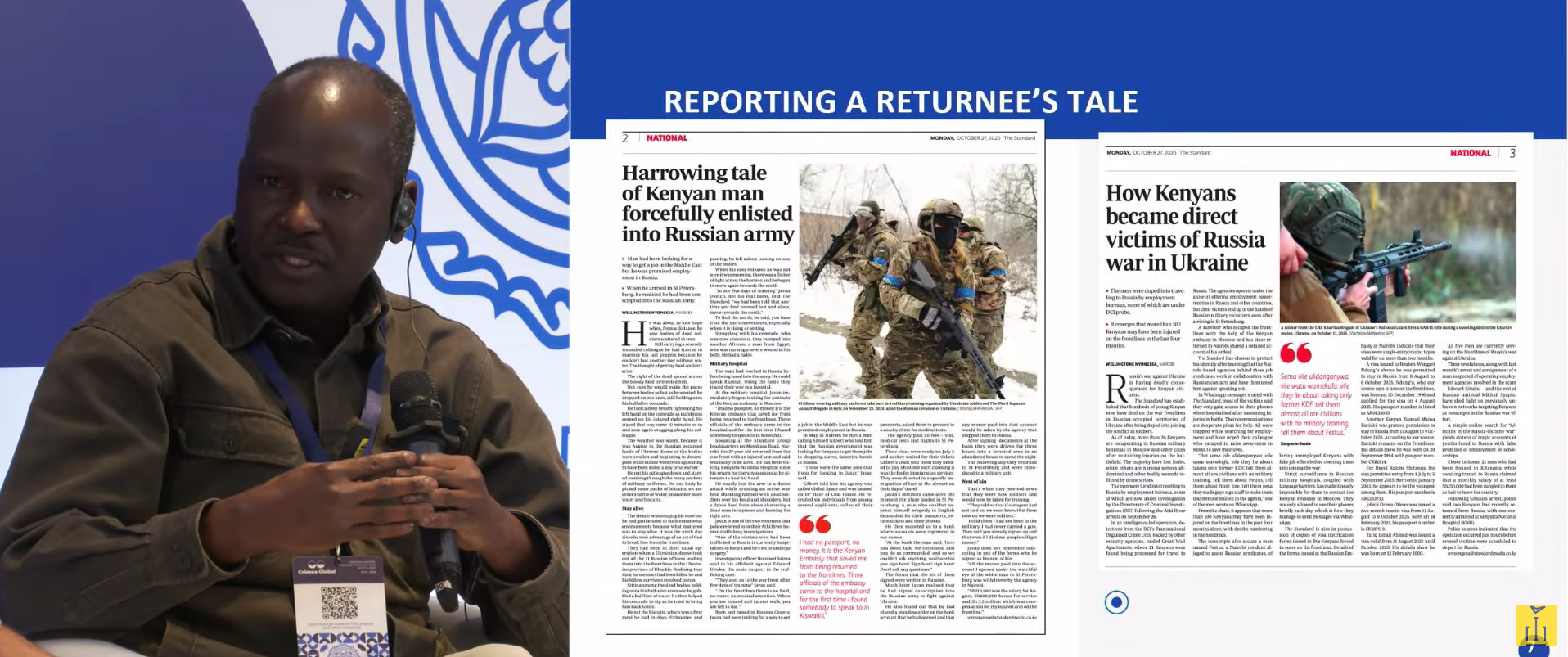

Wellington Nyongesa, intake editor at Standard Group PLC, stated at the Third International Conference Crimea Global that nearly 300 young Kenyan men are trapped on the Russian front lines in Ukraine, lured by false promises of jobs in supermarkets, logistics, and construction.

ZMINA has recorded his speech during the conference.

Wellington Nyongesa

Wellington NyongesaFrom grain crisis to human trafficking

The first impact [of Russia’s war] we felt in Kenya was the grain supply crisis. Several countries in the region buy grain from Ukraine. Months after the war began, food prices surged across the country due to [Russia’s] blockages of sea routes that bring grain to East Africa and the Horn of Africaі .

But two years into the war, reports started surfacing from media outlets and civil society organizations that Russia was recruiting workers for construction sites. The initial targets were young women aged 19 to 25. I first learned about this pattern from colleagues in Zambia and other African countries that had already been affected by these schemes.

Then, in May 2025, the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC), one of the most established civil society organizations researching transnational crime, detailed alleged labor exploitation and human trafficking within Russia’s Alabuga Special Economic Zone (SEZ). The report confirmed what we had already begun reporting based on our own sources: several Kenyan women had been lured with promises of jobs in Russia, only to end up working in war factories.

The Alabuga Special Economic Zone is a large industrial area in the southwestern Russian region of Tatarstan

The Alabuga Special Economic Zone is a large industrial area in the southwestern Russian region of TatarstanRussian independent media and European media broke the story of alleged exploitation and human trafficking within Alabuga’s SEZ, where vulnerable young people from Africa, Asia, and Latin America were recruited under false pretences to work in military drone production for the war against Ukraine.

When victims become props: Alabuga’s publicity campaign

Even before the GI-TOC report was published, we discovered that one Kenyan woman from a village in our country had actually been featured in a Russian propaganda video that denied the factories in Alabuga were manufacturing drones used to attack Ukraine.

As a media house, we produced extensive reporting on Alabuga […], documenting how Russia was promoting the facility and showcasing employment opportunities, using the very Africans who had been trapped there and were working in the factories. We confirmed that approximately 21 women from Kenya alone were among those caught in this scheme. The investigation also continues to reach their families, and the story is still being pursued.

“You do not speak. You only do what we tell you.”

Then, in September, came the bigger revelation. Young men returned home and contacted us. We were unaware that Russia had been recruiting Kenyan men through employment agencies that promised jobs in Russia. This isn’t unusual. Kenyans and people throughout East Africa regularly seek work abroad in hospitality, logistics, security, and skilled positions, particularly in countries such as Saudi Arabia.

Wellington Nyongesa

Wellington NyongesaThese young men told us they had actually returned from the front lines and had been rescued by the Kenyan Embassy in Moscow. They provided us with material we used to break the story. We recognized immediately that this was a major issue, demanding that we inform the entire country so the Kenyan government could act. That’s why we ran this major story on the front page of The Standard, the oldest newspaper in the country and the region.

We obtained and splashed photographs of young men trapped on the front lines. We had documents showing their travel records. The young men shared their harrowing experiences on the front lines and described how employment agencies in Nairobi [the capital of Kenya] had recruited them with promises of supermarket jobs, only for everything to change the moment they landed in St. Petersburg. They were taken to a bank, where they spoke with a man who appeared to be military. He told them, “From now going forward, you do not speak. You only do what we tell you.” And they did what they were told. They signed documents written in Russian, agreeing to things they did not understand.

They were taken to a bank, where they spoke with a man who appeared to be military. He told them, “From now going forward, you do not speak. You only do what we tell you.” And they did what they were told. They signed documents written in Russian, agreeing to things they did not understand.

Then they were sent to military training for five days. They were given guns and placed on trucks headed to the front line. These were men who had never fired a weapon in their entire lives, and they were being sent directly into combat.

The story we published detailed the harrowing account of a Kenyan who enlisted in the Russian army. He survived only because he was injured when a Ukrainian drone struck his unit, killing even the Russian officers who were leading them. He was taken to a hospital, and that’s where Kenyan embassy officials finally located him.

The government’s response

We continued reporting on this issue. The following day, after our front-page story revealing that Kenyans were trapped in Russia and featuring their photographs, the government responded. Prime Cabinet Secretary and Cabinet Secretary for Foreign and Diaspora Affairs issued a two-page statement. The essential point was this: he admitted the government was aware of the situation and had been speaking with Russia’s Foreign Ministry to ensure that Kenyans who had been lured to the front lines would be brought back home.

After the government’s statement, Kenyan families began speaking out because the entire country had started paying attention. About ten families came forward and spoke to the media. Jane Wagngari, the mother of Reuben Ndungu, traveled from one of the towns after seeing her son’s picture on the front page. She went to the Russian embassy in Nairobi and demanded answers about her son. The embassy told her, “We did not give a visa to your son to go and fight, so we don’t know.” She then began to plead with the Kenyan government for action.

Photo credit: Wahito Kanyiri/ Standard

Photo credit: Wahito Kanyiri/ StandardThe Kenyan government’s response has essentially been to engage with the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs to find a way to extract these Kenyans who were lured into the war.

Distinguishing mercenaries from trafficking victims

There are two distinct categories here of how Kenyans and other East Africans ended up in this war. First, we have retired military officials who go there for employment. Those are mercenaries. They are paid. They are trained military personnel. We have several Kenyans serving in this capacity, but they do so for financial benefit.

Then we have this second group, which is quite substantial. We counted almost 300 young men on the front lines. The Kenyan Embassy in Moscow has only established contact with about 82 of them.

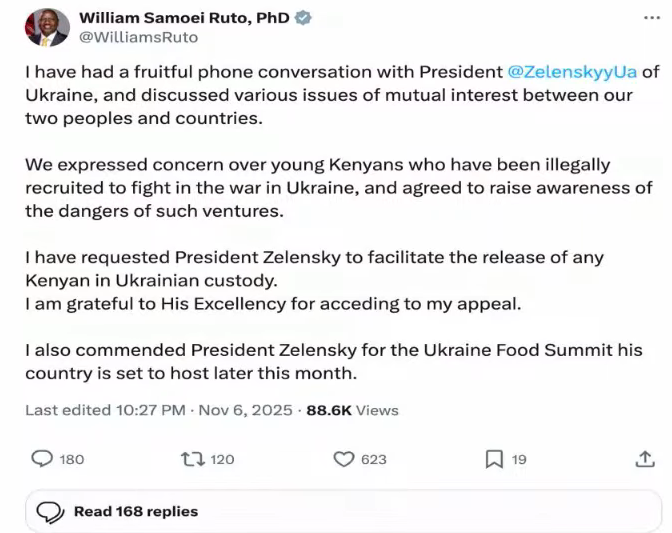

Now, the most interesting aspect of this has been the response that came from Kenya’s President William Ruto. As you can see from his public statements, he chooses to call the President of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenskyy, not the president of Russia. Russia is the country that is entrapping our youth, yet it was not its first point of contact.

We reported on this decision and have been asking the president why he would want to speak to President Zelenskyy about releasing Kenyans when the majority of them are not prisoners of war. We’ve seen reports from Ukraine’s coordination office handling prisoners of war through formal channels, and that is understandable. However, the reality is that the majority of those young men on the front lines have been entrapped by the Putin administration.

The president’s tweet stated he had fruitful conversations with the president of Ukraine and discussed various issues, expressing concern about young Kenyans who have been illegally recruited to fight in a war against Ukraine. He missed the point somewhat. This is something we continue to cover in our media: the person that the Kenyan government should be speaking to is Vladimir Putin.

You may also want to read: Video showing Russian mistreatment of African mercenary spreads among Kenyan social media users

Kenya’s approach to returnees

These individuals are not treated as perpetrators upon their return; no criminal or administrative proceedings are initiated against them.

Kenyan law does not prohibit citizens from serving in foreign armed forces or engaging in military service abroad. This differs from the legal framework in South Africa, where citizens are barred from serving in another country’s military.

Wellington Nyongesa

Wellington NyongesaKenyan authorities view returnees from Russia’s war as victims of coercion and organized recruitment networks that misled them into situations they did not voluntarily choose.

The Kenyan government provides assistance aimed at reintegration, including access to public healthcare and other forms of state support.

Kenyan law enforcement agencies have launched investigations into the recruiters.