Who is now administering “supreme” justice in the occupied territory of Donetsk region

Last year, the Russians were concerned with bringing the justice system of the so-called “ Donetsk People’s Republic” (DPR) to the federal level. Given this illegal formation’s already established and powerful quasi-judicial system, which calls itself a “young republic,” the transformation is particularly interesting.

Who took control of the so-called “Supreme Court of the Donetsk People’s Republic,” what motivated people from Russian regions to start working there, and to what extent local “elites” have retained their presence in the central judicial institution, read in the article.

Let us also remind you that ZMINA previously wrote about who became judges in the occupied Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

Starting from scratch

Three people competed for the post of head of the “Supreme Court of the DPR” – two locals and one “guest” from Saratov.

Among the locals is Svitlana Zarytska, who at the time held the position of deputy head of the court for civil cases. She probably applied as a technical candidate for the formal competition. But the absolute favorite was supposed to be her boss, the former “fighter” against Donetsk organized crime and now acting head of the court, Yuriy Syrovatko.

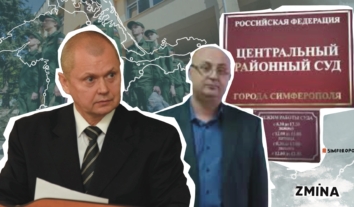

But then Nikolai Podkopaev, the head of the First District Court of Cassation of the Russian Federation, appeared among the candidates. The position of head of a regional court in the occupied territory after managing the “Moscow cassation,” which received cases from 13 subjects of the Russian Federation (including the Moscow region), looks like a clear career downshift.

Nikolai Podkopaev

Nikolai PodkopaevHowever, Podkopaev publicly stated that this was his “conscious choice, which he came to himself and requested.” He explained his motivation by saying he would have to start from scratch in Donetsk.

“It’s always interesting. Later, after you work in a new place, everything will work the way you taught it, the way you arranged it and tried,” the candidate said. It seems that he was not bothered by the fact that the region had formed its quasi-judicial system of 18 judicial bodies eight years ago, which can hardly be called “zero.”

Evil tongues claim that Podkopaev made a “conscious choice” after he was denied the opportunity to extend his powers as head of the Moscow cassation because of compromising materials that are likely to be classified because the information contained in them could “shake Russian traditional moral and ethical values.”

In general, Podkopaev’s demotion to the head of a court in a frontline region is a sign of the ongoing dismantling of the “vertical” of Russian parliamentary speaker Vyacheslav Volodin, for whom Saratov is a base region.

The romance of the “young republic” and the war

When Podkopaev became head of the regional court in Volgograd, he dragged Sergei Sundukov from his former place of work in Kursk and made him his deputy. And when he was promoted to the post of head of the cassation instance, he made three of his Volgograd associates, including Sundukov, his deputies.

Notably, none of these deputies were interested in the “young people’s republic,” but Podkopaev remained faithful to the tradition of moving his subordinates around. Following the former boss, Vadim Vaslyaev and Victoria Filatova, who became deputy chairmen of the “Supreme Court of the DPR,” as well as judges Vladimir Plyukhin and Oleg Krivenkov, the latter known for “upholding” decisions in the interests of officials, changed their cassation appeals to Donetsk realities.

Vadim Vaslyaev

Vadim VaslyaevA certain German Aleksandrov completes the company of judges who “neglected their careers.” He left the resort of Sochi and his office in the Third Court of Appeal of General Jurisdiction for the occupied territory of Ukraine. Aleksandrov explained his motives by saying he liked “hearing cases in the first instance: it is much more interesting than reviewing court decisions on appeal.”

German Aleksandrov

German AleksandrovPreviously, Aleksandrov judged in the Shumyatsky district of the Smolensk region until he suddenly found himself in the Supreme Court of the Chechen Republic. When asked what motivated him to transfer, he replied, “You know, romance. It was interesting to me as a former military man and lawyer.” The judicial experience and romantic approach he gained in Chechnya will now find wide application in Donbas.

Import of Russians

If one assesses the general changes in the judicial system, which has long had its backbone, connections, and traditions in the so-called “DPR,” the policy of replacing Ukrainian collaborators with imported judges becomes obvious.

Of the 40 judges identified by open sources, less than half – 19 – are local judges in the “Supreme Court of the DPR.” The rest come from district courts in various Russian regions. Among them is a notable group of people close to the heads of the Saratov and Volgograd regions, and almost a third are from the Volga region – Perm, Penza, and Orenburg.

Mikhail Pursakov, who had previously worked for 12 years in the Krasnoyarsk Regional Court, 4,500 kilometers from the occupied territories, took the longest path to the seat of a judge of the “DPR Supreme Court.” What inspired him to make such a change is unknown.

Some other judges’ motivations were voiced while considering their candidacies. For example, Judge Jamila Kochegarova explained that she was attracted by “favorable climatic conditions,” while Judge Aleksey Kovalenko decided to change location to “bring the most benefit.”

However, the key motive in replacing judges is likely career advancement. Of the 21 Russians, only the chairman and five judges took an apparent demotion “for the sake of romance” and “starting from scratch.” Valentina Oleynikova, Yuri Khrapin, and Mikhail Pursakov were transferred from equivalent positions in regional and territorial courts. For 12 other Russian judges, the appointment to the “Supreme Court of the DPR” was a noticeable career advancement after working in city and district courts of general jurisdiction.

Valentina Oleynikova

Valentina Oleynikova Yuri Khrapin

Yuri KhrapinThe fact that by their participation, they are perpetuating a violation of international humanitarian law, which prohibits the extension of the occupying power’s legislation to the occupied territory, obviously does not bother them.