Signs of genocide: Russia’s crimes against children – Report

After the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, information began to emerge about the transfer of children by Russian occupying forces from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. The children were taken to the Russian Federation, the Republic of Belarus, or the territories of Ukraine occupied by the Russian Federation before February 24, 2022, namely, parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk region and Crimea.

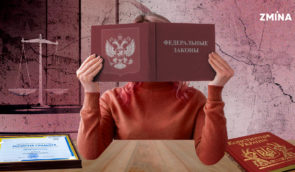

Analysts of the ZMINA Human Rights Center (ZMINA) have studied Russia’s policy of displacement of Ukrainian children. Human rights defenders concluded that these processes are carried out on the initiative and with the broad support of the Russian leadership, which aims to destroy the ties of Ukrainian children with their national group and make it impossible for them to return to Ukraine.

Evidence and examples of how Russia is committing the crime of genocide against Ukrainians were presented by human rights defenders of ZMINA in the report “Forced Displacement and Deportation of Children from the Temporarily Occupied Territories of Ukraine to Russia.”

While working on the report, experts used data from open sources and testimonies documented by the organization from people who have suffered or witnessed deportations and forced displacement of children. The report covers the period from the beginning of the full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022, to March 11, 2023.

Here is a summary of the report.

First ‘evacuations’

Donetsk boarding school No. 1 students were among the first to be taken to Russia. Source: freeze frame from the video in social media

Donetsk boarding school No. 1 students were among the first to be taken to Russia. Source: freeze frame from the video in social mediaThe Russians persistently call forced displacement, transfer, and deportation of civilians as “evacuation.” As if demonstrating how they are saving Ukrainian children from war. At the same time, according to international humanitarian law, public safety and military necessity are not permissible grounds for transferring children out of the country.

The study showed that Russian occupation authorities took children from children’s institutions in the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions to Russia even before the full-scale invasion.

“For instance, an ‘evacuation’ from the ‘DPR’ [so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, part of the Donetsk region occupied by Russia since 2014] and the ‘LPR’ [so-called Luhansk People’s Republic, part of the Luhansk region occupied by Russia since 2014] was announced on February 18, 2022. Already on February 19, 2022, the first buses with 225 pupils of Donetsk boarding school No. 1 arrived at the Russian border,” the report says.

Children from Donetsk boarding school No. 1 and two other Donetsk orphanages were placed in the Romashka sports and recreation complex in the Neklinovsky district of the Rostov region of the Russian Federation. Romashka accommodates 457 children.

“On April 23, 2022, an interview appeared with the director of the institution, who stated that the decision to evacuate was made ‘in a matter of minutes’ before the full-scale invasion, and all the children ‘gave their consent’ to be transferred to families in Russia,” the study says.

It was much easier to remove children’s institutions located in the territories of Ukraine occupied by Russia before February 24, 2022, due to the existing mechanisms and occupation infrastructure already developed over a long time. However, the Russian Federation is not limited to these territories. Russia also carries out forced transfers and deportations of children from the territories occupied after the start of the full-scale invasion.

For example, in March 2022, under the pretext of evacuation, the Russian armed forces forcibly transferred 12 underage patients of the regional children’s bone and tuberculosis center in Mariupol to the occupied part of the Donetsk region. Another 14 children – residents of two family-type orphanages – together with three foster parents were taken from Mariupol to the Rostov region of the Russian Federation.

This practice has also become widespread in the Kherson region in the South of Ukraine, which was occupied in the first weeks after the start of the full-scale Russian invasion.

Children were hidden in the Kherson region to avoid handing them over to the enemy

Russian soldiers came for children at the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children. Source: freeze frame from CCTV cameras

Russian soldiers came for children at the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children. Source: freeze frame from CCTV camerasFrom open sources, human rights defenders learned how persistently the occupation authorities tried to remove children’s social institutions from the Kherson region. And how the heads of these institutions, legal guardians, protected their children.

For example, the director of the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children of the Kherson Regional Council, which housed 52 children, handed some children over to their parents or relatives – grandparents, etc. – under Ukrainian law. Seventeen children who did not have close relatives were taken to their families by the institution’s staff.

When the Russian occupying forces came to the institution in early July, five boys aged 14-17 refused to go to Russia for rehabilitation.

As of today, almost all the children of the Center have been evacuated to institutions in safer cities in Ukraine.

Meanwhile, on July 15, 2022, the Russian military brought 15 orphans to the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children of the Kherson Regional Council. They were pupils of the Novopetrivska Special School (legal name – Municipal Institution ‘Novopetrivska Special School’ of Novopetrivka village, Snihuriv district, of Mykolaiv Regional Council), which was located on the front line at the time. The principal of the Novopetrivka Special School was with them.

The Russians were watching these children throughout the entire time, and the management of the institution was unable to hide them. The children lived in the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children of the Kherson Regional Council until October 19, 2022. When the Russian military retreated from Kherson in early November 2022, they took the children and the director of the Novopetrivska Special School with them.

The director of the Center for Social and Psychological Rehabilitation of Children of the Kherson Regional Council was told they were being taken to Henichesk, Kherson region. Three days later, she contacted the director of the Novopetrivsk Special School, who was moving with her students. She reported that they were brought to the city of Anapa in the Krasnodar Territory of the Russian Federation. The long rescue operation began.

Now, the pupils of Novopetrovsky Special School are safe in Georgia.

“From the organized and massive number of cases of removal of institutions responsible for the care of children, we can conclude that the Russian Federation is deliberately implementing a policy of forced displacement and deportation of children from Ukrainian children’s institutions,” human rights activists believe.

‘Rest’ and ‘recovery’ with re-education

Children from Donetsk and Lviv regions are undergoing ‘re-education’ in Chechnya, Russia. Source: freeze frame from the video

Children from Donetsk and Lviv regions are undergoing ‘re-education’ in Chechnya, Russia. Source: freeze frame from the videoDuring the temporary occupation of territories of the Kharkiv and Kherson regions, Russian forces introduced the so-called ‘retreat’ for children. Children from families and children’s institutions were sent ‘on vacation’ to Crimea [a peninsula occupied by Russia since 2014], to the south of the Russian Federation, or to the Republic of Belarus. Then, they refused to return children to their parents or legal guardians.

“On September 10, 2022, the Ministry of Labor and Social Development of the Krasnodar Territory of the Russian Federation announced that children from the Kharkiv region, who are on vacation in Gelendzhik, will stay in the camp for another shift ‘due to security reasons.’ On September 22, Kuban state media reported that 223 children from the Kharkiv region were enrolled in elementary school No. 7 in Gelendzhik,” ZMINA’s report says.

The human rights organization’s analysts concluded that in cases where parents were offered to send their children ‘on vacation,’ the Russian side actually abused their vulnerable state, their desire to protect their children from shelling and the difficulties of living in the occupied territory, for example, in the absence of food. At the same time, Russian occupying forces restricted the ability of people to travel to the part of Ukraine. Parents were also offered to sign a ‘consent to the transfer.’

“Parental consent to send their children to the camps can hardly be called free, given the intimidation, the dire humanitarian situation in the occupied territories, the restrictions on travel to the government-controlled territory of Ukraine, and the misleading information about the nature and duration of such ‘vacation.’ Parents admit that if they had known these circumstances in advance, they would not have sent their children away,” the analysts say.

Human rights defenders found that one of the primary purposes of sending children from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine to camps in Crimea and the Russian Federation is ‘re-education’ – the integration of Ukrainian children into the education and leisure system approved by the Russian government. At least 32 of the 43 established camps actively and systematically provide Russian-style ‘education and cultural development’ for Ukrainian children. The program includes Russian narratives about the nature of the full-scale invasion and the history of Russian-Ukrainian relations.

In particular, according to the so-called ‘Minister of Education, Science and Youth of the Republic of Crimea’ Valentyna Lavryk, children’s camps in Crimea and the regions of the Russian Federation pay much attention to educational work with children from the ‘DPR’ and ‘LPR,’ as well as from the occupied parts of the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions. Russian occupying forces regularly hold ‘Conversations about the important things.’

For example, as part of the program dedicated to the Day of the Defender of the Fatherland in Russia, Ukrainian children discussed the Russian army’s ‘peacekeeping operations’ in Nagorno-Karabakh, South Ossetia, and Kazakhstan. They also discussed the defeat of terrorists in Syria, the protection of compatriots, and the liberation of Donbas (parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions) during a special military operation. Their attention was focused on the fact that Russia is a country that uses its armed forces exclusively to maintain global peace.

A separate program was planned for so-called ‘difficult adolescents.’ Two hundred such teenagers from Russia and teenagers from the ‘LPR’ and ‘DPR’ were brought to the Russian University of Special Forces in Gudermes, Chechnya, for ‘preventive work for the military and patriotic education.’ There, they were given a tour of the training ground and a lecture about the ‘heroes of the National Guard of Russia.’

Thus, the Russian authorities are not only teaching Ukrainian children according to Russian educational standards, which include false information about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They are also re-educating and militarizing these children.

“All these activities are carried out on the initiative and with the broad support of the highest political leadership of the Russian Federation. According to the Russian curriculum, as well as additional extracurricular activities organized by the Russian Federation, education in camps and schools is aimed at destroying the ties of Ukrainian children with their national group and making it impossible for them to return to Ukraine,” the analysts believe.

Instead of two weeks, children stayed on these ‘vacations’ for two to six months. They were refused to be returned to their parents for various reasons.

Children from the Kharkiv region travel by bus to the Krasnodar Territory in the Russian Federation on August 6, 2022. Photo: krd.ru

Children from the Kharkiv region travel by bus to the Krasnodar Territory in the Russian Federation on August 6, 2022. Photo: krd.ruFor example, a 14-year-old boy from Kherson was sent to a camp in Crimea by his mother on October 4, 2022, and was supposed to return in two weeks, but two months passed. At the end of November 2022, he sent his mother several voice messages from the camp’s director, who said that he would not be allowed back to Kherson because of his pro-Ukrainian views. The camp management extended the boy’s stay, citing security concerns. Then, when Ukrainian troops entered Kherson, they said he could not return because the city was now ‘occupied’ by Ukraine.

In some cases, the leaders of the Russian camps stated that they had no plans to return Ukrainian children. In other cases, children were moved from one camp to another without informing their parents.

Guardianship and Russian citizenship

Illustrative photo of a Russian passport from open sources

Illustrative photo of a Russian passport from open sourcesRussians do not look for their relatives when taking Ukrainian children from the temporarily occupied territories to Russia. Instead, they place them in Russian families.

“The placement of children in Russian families instead of a proper search for relatives in their national group and the transfer of such children to the responsible authorities of Ukraine also signals a planned campaign of forced exclusion of these children from the Ukrainian national group,” the report says.

Human rights defenders identified that in early April, the Moscow region proposed a project to help find guardians for children left without parents in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. They planned to search for relatives only in Russian state and Red Cross databases.

For example, two children aged eight and nine were transferred from a boarding school in Donetsk to a foster family in the Moscow region. It is known that their grandmother lives in Mariupol.

These are not isolated cases recorded by ZMINA analysts. For example, a group of children from a Mariupol sanatorium who had guardians were taken by Russians to occupied Donetsk. One of the members of this group said that when representatives of the occupation ‘Donetsk Children’s Service’ contacted the guardian, they demanded the children’s data to make them ‘DPR documents.’

They also threatened that if the parents did not come to pick up the children at the ‘DPR,’ they would leave them there, make documents, and transfer the children to a different family. This was said to both the guardians and the children themselves every day.

In early August 2022, the Russian Presidential Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, reported that 160 children from the so-called ‘DPR’ territory had already been placed in Russian families, 133 of whom had already received Russian citizenship.

“The Russian Federation violates its obligations to respect the child’s right to preserve his or her identity, including citizenship, name, and family ties, and the prohibition against changing the civil status of children by transferring them to the care of Russian citizens, without conducting a proper search for their relatives and without notifying and transferring such children to the responsible authorities of Ukraine,” ZMINA analysts conclude.

Human rights defenders also report that Russian families receive financial payments in the guardianship and custody procedure. In particular, for 2022, the one-time fee amounted to 20,472.77 rubles (approximately ~$220). At the same time, if the child under guardianship has a disability or is over seven years old, or the family simultaneously takes in siblings (does not separate them), the amount increases to 156,428.66 rubles (~$1675). The amount is calculated for each child separately.

In addition, monthly payments are provided for such parents, which can be arranged simultaneously with the lump sum payment, which parents can receive until the child turns 18. These payments can be made to both the child and the guardian.

“However, if the payments are transferred directly to the child, he or she cannot freely dispose of them – only with the permission of the guardianship authorities. If the parents receive the payments, they can dispose of them, with only possible checks from the guardianship authorities. Monthly payments depend on the region of residence. For example, in Moscow, in 2022, parents received 18,150 rubles per month (~$195),” human rights activists explain.

Analysts at the ZMINA Human Rights Center have concluded that measures to simplify the adoption of Ukrainian children, recognize them as Russian citizens, and educate them within the Russian education system violate the obligation to respect the child’s right to preserve his or her individuality.

“Such actions by the Russian Federation are aimed at severing the children’s connection with Ukraine, making it impossible for them to return, and have signs of a crime of genocide in terms of the forced transfer of children from one human group to another,” the report says.

According to the official data of the Ukrainian authorities, Russia deported more than 19,000 children from Ukraine during the year of war. Of these, 4,390 were children from special children’s institutions – orphans, half orphans, or children deprived of parental care. According to open sources in the Russian Federation, the Russians took 744 thousand children. The European Parliament believes that since 2014, Russians have deported up to 300,000 Ukrainian children.

Some of those who have been returned to Ukraine tell of abuse and threats to send them to an insane asylum, of the terrible conditions in the so-called ‘camps,’ of ideological re-education, and of being treated like animals by the administration and educators.

On March 17, 2023, the International Criminal Court in The Hague issued an arrest warrant for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russian Children’s Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova. The court said in a statement that Russian officials are suspected of the war crime of illegally deporting children from Ukraine to the Russian Federation. It is believed that the President of the Republic of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, has assisted with the deportation of children from Ukraine to Belarus. Children from the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine are also being taken to Belarus for ‘retreat.’

Experts from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe also collected data on the deportation of children to Russia.