Four stories of missing persons in the occupied territories of Ukraine

For over a year and a half of full-scale Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, thousands of Ukrainians have gone missing under the rubble of destroyed buildings, in artificially flooded areas, and Russian prisons. It is still not known precisely how many people have disappeared due to the war unleashed by Russia. According to the register of missing persons under special circumstances overseen by the Commissioner for Missing Persons of Ukraine under the auspices of the Ombudsman’s Office, the number of such persons is at least 25,000. The fate of at least 7,000 is still unknown.

Residents of the occupied cities and towns live in constant fear: Russian soldiers can break into their homes at any time, severely beat them or their relatives, put a bag over their heads, put them in a car, and take them to an unknown destination. The abductees’ families often do not know where their loved ones are being held, how they feel, or whether they are alive.

ZMINA retells four stories about the abduction and disappearance of Mykola Harbar, a hunter; Vasyl, a handyman; Volodymyr Khorolsky, a territorial defense volunteer; and Artur Baranets, a policeman.

Mykola, who Russians abducted along with his car

Before the war, Tetiana and Mykola Harbar lived in the village of Novokairy on the right bank of the Kherson region.

Mykola Harbar. A photo provided by his family

Mykola Harbar. A photo provided by his familyImmediately after the occupation of the village, in March of 2022, the Russian occupying forces began going from house to house, checking documents, and confiscating weapons from locals.

The villagers knew that the Russian military had lists of local hunters. Mykola was probably on one of them: he had a rifle.

When the Russians first came to the Harbars’ home, they immediately asked about weapons. Mykola admitted that he had a rifle and ammunition. The Russian occupying forces confiscated them and all the permits but did not touch the family first.

Later, his wife moved to the territory controlled by the Ukrainian government, and Mykola stayed behind to take care of the house and the farm.

Tetiana recalls that she could not reach him before her husband’s abduction and was very worried.

On August 20, 2022, the woman received a phone call from her neighbors, who told her that Russians had come to their house for the second time and taken Tatiana’s husband with them two days earlier.

The neighbors said that on that day, a Tiger armored vehicle drove up to their gate, from which four soldiers got out and headed to the couple’s house. The occupants spent a lot of time inside, but no one knew the circumstances of the man’s detention.

According to witnesses, Mykola opened the gate himself after a while, got behind the wheel of his car, with one of the Russian military already sitting in the front, and drove off in an unknown direction.

Later, the neighbors told Tetiana that while the Russian soldiers were in the house, one stood on the doorstep and kept looking at the locals.

“That’s why the Russians didn’t like that the neighbors were watching their actions. They assumed that he was the one who was in charge. When he opened the gate, my husband managed to wink at ours, hinting that he was being taken away,” the woman says.

Witnesses told Tetiana that Mykola was taken away wearing a T-shirt and shorts, which he had been wearing while working in the garden.

After the Russians left, neighbors with spare keys went to the Harbars’ house to lock the doors and gate. They saw that the place had been searched: the cabinets and the safe were open, and there was no money, phone, or documents. Later, the neighbors accidentally found Mykola’s laptop, which he had managed to hide under the sofa.

One of the witnesses told Tetiana that he saw her husband leaving the village in a car with a Russian man. Other villagers said they saw Mykola beaten.

“We assume the man could have been held in Beryslav or Nova Kakhovka. It was there that Russians usually kept civilians abducted from local villages. There were also rumors that he was taken to Crimea. But we don’t know anything about him for sure. He just disappeared,” says Tatiana.

To find out about Mykola’s fate, a friend of the Harbar family went to the Beryslav “commandant’s office.” Later, this friend told Tetiana that as soon as she mentioned her husband’s name, the Russian soldiers became enraged and hit her in the back with their rifle butts.

One of the Russians asked why she was interested in Mykola.

“He is my relative. I’m just asking,” the woman replied.

After that, the soldier took her to the Beryslav Machine-Building Plant, where civilian hostages were being held. There, she saw severely beaten people, one of whom was barely breathing and appeared to be half alive. There were also bodies of the dead in the room. However, she did not see Mykola there.

At that moment, the woman thought that she would not be released after what she had seen.

“Then, one of the Russians told her to leave and not to come back. After that, my friend left the occupied territory because she feared for her life,” Tetiana recounts those events.

Mykola’s wife suggests that her husband could have been handed over to the occupiers by a local collaborator who owned a chain of stores. In return for his cooperation, the Russians appointed him a village head. When the right bank of the Kherson region was de-occupied in early November 2022, the man fled with other collaborators.

After Mykola’s disappearance, Tatiana appealed to the National Police, the Security Services of Ukraine, the Prosecutor’s Office, the Ombudsman, the Coordination Headquarters, the National Information Bureau, and the International Committee of the Red Cross. Still, she was told everywhere that there was no information about her husband.

Vasyl, whose house was moved into by people who lost their homes due to shelling

Vasyl’s wife Olha (name changed for security reasons – Ed.) remembers well how, in September 2022, the Russians finally occupied their village in the Kharkiv region: before that, Russian army columns passed the town without stopping.

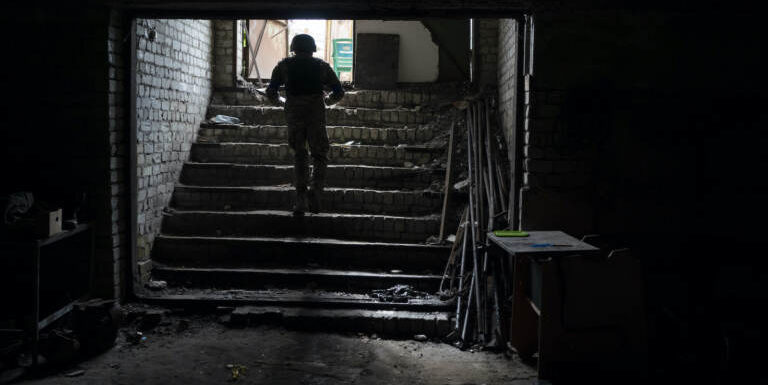

A photo by Leo Correa

A photo by Leo CorreaThe Russian military immediately began occupying empty houses, checking documents, and searching residents’ homes.

“They would just come to people’s homes and take them away. They turned everything in the houses upside down. They even took the cattle with them,” the woman says.

One day, according to his wife, when Vasyl was carrying pies to a neighbor, the occupiers made him kneel in the middle of the street, put an assault rifle to his head, and asked him questions.

“Who are you? Where are you going?”

The Russian occupying forces had already started taking away residents at that time.

“People started disappearing immediately from our village and the neighboring one. The occupiers abducted at least ten people. Some said they were taken to Luhansk region or even Belgorod, [Russia],” the woman says.

Olha recalls that the Russians took and released one man from a neighboring village three times until he left the occupied territory.

Six months ago, the woman adds that the Russians also took a married couple from a neighboring village. The reason was allegedly that their son was a soldier. Like with the other abducted men, their fate is also unknown.

Olha says that some people in their village were happy to see the Russians. For example, according to the woman, Russians often came to their neighbor’s house, and she fed them.

“It was scary to say anything because your people could immediately turn you in. That’s why people preferred to keep silent to avoid trouble,” recalls a woman.

After a month of living under the occupation, Olha moved in with her children, who had been taken to the government-controlled territory even earlier. She hesitated for a long time and did not want to leave Vasyl alone in a hostile environment. Eventually, she agreed, and a neighbor who had returned from Kharkiv to collect his belongings helped her leave. The neighbor suggested that they go through Belgorod to Sumy.

The biggest obstacle on this path was passing the “filtration.” Olha was interrogated for three to four hours: where she was born, who her parents are, whether they are alive, where she studied, with whom she was friends, how old her children are, where they studied, how she feels about the military, where she is going, etc.

“Imagine this: you are taken to a basement with two chairs and a barely lit lamp. A Russian man sits across from you, constantly looking you in the eye and smiling like a boa constrictor. The atmosphere in the room is very depressing,” Olha recounts her experience.

From Sumy, the woman went to Kharkiv; from there, she and her children went abroad.

Vasyl would periodically call her and tell her about household chores, animals, and gardens.

On March 20, 2023, her husband stopped contacting her. On April 10, Olha wrote to a fellow villager whose relatives remained in the occupied territory and asked her to ask them about her husband. Then, the woman told Olga that on April 8 or 9, Vasyl was abducted by Russians.

“She knew the occupiers had taken my husband but did not dare tell me about it. My friend could not find the right words. After hearing that, I felt sick – my hands started shaking, and tears started flowing,” says the missing man’s wife.

The Russians gave the keys to the couple’s house to a neighbor who was friends with them. She moved in people from a neighboring village who had lost their homes after the Russian bombing. They had been staying with her for two weeks already.

The couple’s home was full of belongings, appliances, and everything the family had accumulated over the years of their marriage.

After Vasyl’s abduction, nothing is known about his whereabouts and health condition.

“We don’t know where to look for him. We contacted the National Information Bureau, the Coordination Center, and the International Committee of the Red Cross. His parents filed a statement with the police and took a DNA test.”

Currently, there is no communication with the occupied village, and information can only be obtained from people who have left.

Frightened villagers who remain there are afraid to talk about the missing man. However, rumors sometimes circulate that all the detainees were first taken to Troitske in the Luhansk region and then to Horlivka, Donetsk region.

Volodymyr, who is considered a prisoner of war by the Russians and is being held for exchange

Before the war, the Khorolsky family lived in the village of Mylove, Kherson region. After the occupation, the Russians took Volodymyr away twice, says his mother, Natalia. While the first time he was released, he went missing after the second.

Natalia recalls how, on July 3, 2022, at 11 a.m., she went to the store, and when she returned, she saw military equipment near her house.

Approximately six Russian soldiers blocked the street and did not allow anyone to pass. They were wearing military uniforms and balaclavas and carrying assault rifles.

The woman had to explain that she lived in this house. Eventually, Natalia was let in, but they checked her phone beforehand. She never saw Volodymyr. As her neighbors later told her, he was put in a car with a bag over his head and taken in an unknown direction.

When the woman asked the Russians why her son was detained, they said he was taken for “communication.”

“I got the impression that the Russians knew everything about my son even before they came,” Natalia adds.

One of the soldiers added, “Wasn’t he in the territorial defense? Does he have a weapon?”

Natalia replied that her son only went to training camps but did not fight or serve and did not have a weapon.

The Russian military turned everything in the house upside down, with things from the closets lying on the floor. They also climbed into the attic and inspected the barn. The woman says after the search, the Russians took her son’s phone, passport, military ID card, and a digital TV tuner.

After Volodymyr’s detention, Natalia went to the occupation “commandant’s office,” where she was met by officials of ‘DPR’ [so-called Donetsk People’s Republic, part of the Donetsk region occupied by Russia since 2014] who told her that they had nothing to do with the Russians.

The woman went there the next day and was advised to look for her son in Nova Kakhovka. She went there as soon as public transportation was restored.

At the occupation ‘police’ department in Nova Kakhovka, Natalia was told that Russia’s Federal Security Service was holding her son. However, the department denied this. The woman insisted that her son was being held there and that she knew about it. Only then was she allowed to enter, but she was thoroughly searched.

“One of their employees approached me and didn’t even introduce himself. He confirmed that they had my son. I asked if I could see or give him something, and the Russian replied: “It’s not allowed,” the woman recalls.

The next time Natalia came to the location again, the man who had detained her son came out to her. According to her, she recognized him by his eyes.

The woman asked why her son was taken away.

“He was in the terrorist defense. He has a rank and a military ID,” the Russian replied. “He has a unit to which he is assigned. Therefore, he is considered a prisoner of war, whom we may try to exchange shortly.”

The law enforcement officer allowed Volodymyr to hand over the parcel but refused to see him.

“I don’t know what he looks like now, what’s wrong with him, whether he received the package. I don’t even know where he is being held.”

Arthur, who could be confused with a special forces officer

Artur Baranets was a police officer and later a volunteer in Irpin, Kyiv region. According to his father, Yurii, after the Russian invasion, Artur and his colleague Ruslan Filipenko evacuated more than ten families from the city and its outskirts to the country’s western regions.

Artur Baranets. A photo provided by the family

Artur Baranets. A photo provided by the familyOn March 2, 2022, Artur, along with Ruslan and two terrorist fighters, Oleksii Yashchenko and Denys Derevianchuk, took hygiene products and food to a village near Vorzel on the instructions of the Irpin defense headquarters.

Arthur’s father recalls that active hostilities were already taking place around Irpin, and the situation was changing every hour.

On their way back, the Russians fired with a tank machine gun at the jeep they were traveling in. This happened on the road between Vorzel and Mykhailivska Rubezhivka.

“The car was damaged, and they were all taken prisoner. One of the Russians deliberately stabbed Derevianchuk’s leg with a knife,” Yuriy recounts everything he learned about that day.

The man notes that everyone in the car was carrying small arms.

“They were dressed in black uniforms like police officers. The Russians probably confused them with special forces,” the kidnapped man’s father suggests.

The man recalls how a video on YouTube in early March showed the Russian military interrogating police officer Filipenko. In the video, the prisoner talks about how he joined the territorial defense, where he traveled with other men, how they interacted with the Armed Forces, and who their leader was.

The Kremlin’s Russia 1 TV channel aired a story about Arthur in late March last year. In the video, the occupiers asked for the password to the phone from a beaten man on his knees.

“The video ends quickly. We saw that the guys were captured thanks to this video and the previous one. Judging by the conversation, he was interrogated by a Russian soldier or a person from the special department. He knows how to communicate and knows how to behave. It was not a simple soldier,” the father suggests.

Later, witnesses told Yurii that the Russian military interrogated the men, took them to the firing squad, and mocked and tortured them.

The man was also told that sometimes the occupiers tied prisoners to a tank and drove with them. They also used men as “mattresses” – that is, they sat on them.

Yuriy knows that Artur and the others were kept in cold rooms at the Hostomel airport.

On March 5-6, all four abductees were transported through the Chornobyl zone to Belarus and Russia.

Arthur’s father received information about his son’s and other men’s further stay. At first, they were allegedly held in Kursk and then – in Sevastopol, Crimea, but the relatives of the disappeared still have no accurate information.

“We do not know their whereabouts or their health condition. The International Committee of the Red Cross does not have this information either,” emphasizes the father of the missing man.

When the men were first abducted, their families had trouble determining their statuses. As Yurii explains, on February 26, 2022, Arthur and Ruslan joined the ranks of the Irpin Territorial Defense. However, this military structure was officially registered later – on March 22. Thus, during their detention, the men were civilians under international law.

Instead, Russia classifies them as prisoners of war.

His father said there was also confusion in Ukrainian agencies about Arthur’s status.

“They belonged to an unregistered organization that was not formally affiliated with the Armed Forces. In addition, on March 8, my son and his friend Filipenko were fired from the police for failing to report for work. Therefore, they were initially classified as civilians in Ukraine, but their status was changed to ‘prisoners of war.’

In Yuriy’s opinion, this may have contributed to the fact that the men have been in captivity for over a year and have not been exchanged.

Yuriy also suggests that law enforcement officers did not conduct an internal investigation into the detention of his son by the Russians.

Arthur’s father hopes that his son will be found in one of the Russian prisons, that they will be able to contact him, and that he will eventually return home.