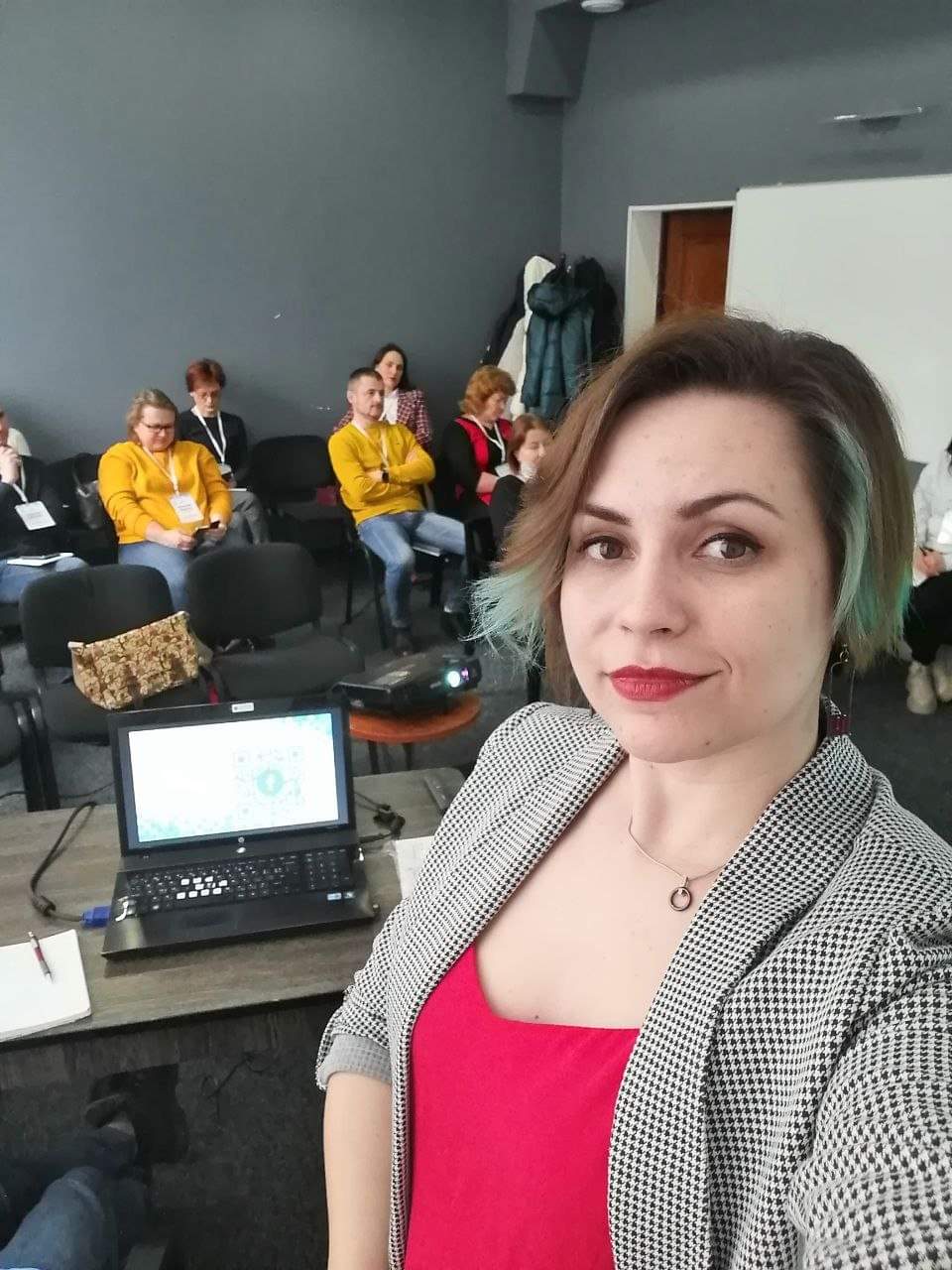

Discrimination has a chain reaction: if you start with one group, you can end up discriminating against anyone – family doctor Daryna Dmytriievska

During the war, Ukrainians face a variety of challenges, including difficult access to healthcare services due to the reduced number of doctors. For the LGBTIQ community, this issue is further complicated by the stigma and discrimination that can occur in healthcare facilities. However, there are those among healthcare professionals who actively advocate for equality and support for LGBT+ patients.

ZMINA spoke to Daryna Dmytriievska, a family doctor, civil society activist and co-founder of the Medical Leaders organisation, about how to ensure access to quality and non-discriminatory healthcare for LGBTIQ people.

Nowadays, LGBTIQ groups often discuss the search for friendly doctors, but 10-15 years ago it was hard to imagine. How did you decide that you would support LGBTIQ people, both in practice and in the public space?

In fact, there was never a specific decision about this, I have always been LGBTIQ friendly. In 2017, I attended a training session from the NGO Insight on working with transgender people, after which I realised that I could not only be LGBT+ friendly in my practice, but also speak about it publicly and help people.

Having a certain authority as a doctor, I realised that I could change someone’s attitude or at least have the right to speak publicly as a specialist and scientist. In 2017, I started accepting transgender people and the LGBTIQ community in general. I help with transitioning and act as an expert at trainings on the management of LGBTIQ people. It all happened naturally because this topic has never been a problem for me. I can do it and that’s why I do it.

Are there any specifics in working with LGBTIQ people? In general, if we are talking not only about gynaecology, venereology or urology?

There are practically no peculiarities, unless we are talking about transitioning, where we do have medical nuances, for example, in prescribing hormones or preparing for surgery – these are purely medical procedures. Otherwise, there is no difference, because we have to be open to all our patients. I don’t really like the word “tolerance” because it creates a distance – as if I am here and there is someone else to whom I have to be tolerant. In fact, there is no significant difference between us: there are just people who need medical care.

This is especially true for family medicine, which is my speciality. There is no difference at all. As for gynaecology, if it is a woman who does not have heterosexual intercourse, this can only reduce the risks of sexually transmitted infections and eliminate the risks of unwanted pregnancy. Everything else remains the same.

It is important to understand that all people, regardless of orientation, gender identity, race or religion, need to be treated equally. Doctors must be ethical and keep medical confidentiality, which, unfortunately, is sometimes violated, especially in relation to LGBTIQ patients. Some doctors start to share personal details of patients’ stories with colleagues or condemn a person’s lifestyle or identity, which is completely unacceptable. A doctor has no right to do this, regardless of any signs.

You mentioned non-disclosure of medical confidentiality, and I thought of this. This aspect, as well as the possibility of making decisions regarding the health of a partner, is also important in the context of civil partnerships. Do you agree with this?

Absolutely. For people who want to get married or enter into a formal partnership – regardless of orientation, gender or sex – all rights should be available. We are talking about the legal aspects when, for example, your partner is in intensive care and you need to make a decision about treatment.

LGBTIQ people who are in a relationship should have the same rights as those who are considered to be close relatives: not to testify in court, to make important health decisions, etc. But now, part of society has these rights, while the other part, even after dating and loving each other for a long time, is legally considered to be nobody to each other.

Of course, I support partnerships and always speak openly about it.

Thank you for the clarification. Please tell us, did the full-scale war have any impact on the healthcare needs of LGBTIQ people?

The needs of all people, regardless of whether they are LGBT+ or not, for medical care, examinations and treatment remain the same as before. The problem is the lack of doctors. Even before the war, it was a problem, and now, during the war, the situation has worsened, as some doctors have gone abroad and others are at the front. Therefore, it has become even more difficult to find a good doctor, especially a friendlier one.

In particular, in the context of transitioning, where it is important to have doctors who understand the topic and support patients, a serious problem arose. Before the full-scale invasion, there were trainings for doctors on how to work with transgender people. For example, activists, including Tania Kasian and myself, were involved in this.

We already had a small number of doctors who were trained and able to help. But now many of these doctors have either moved or changed jobs. Some went to the frontline, others went abroad. And now it has become even more difficult to find or recommend a friendly doctor of any speciality. Those who are left have a huge workload, and the opportunities to conduct new trainings are now limited.

This is even more problematic because the medical community is very conservative and not always willing to take part in such training. They say that there are other priorities: the war, first aid training, work with the mental health of veterans, etc. And although all of this is really important, the problems of LGBTIQ people do not disappear.

There are veterans among the LGBTIQ community, as well as military personnel who protect us at the front, and they face the same challenges as everyone else, but with additional difficulties.

With the start of the full-scale invasion, these challenges have only intensified. The number of requests for medical examinations and treatment, especially in the context of transitioning, has not decreased. I receive such requests almost every week, but unfortunately, I often have no one to advise me.

I live in Zaporizhzhia and I can also note that there are significantly fewer doctors here. And this is logical, because it is a frontline city. I’ve heard of cases where LGBTIQ people who are subjected to violence by the occupiers in the temporarily occupied territories do not seek medical treatment because they are afraid of disclosing their gender identity or sexual orientation. Have you heard of this?

By the way, there are quite a few friendly doctors in Zaporizhzhia, particularly in family medicine. I personally know several doctors and medical institutions with very modern management. I have conducted trainings for them, and they have contacted me, declaring their readiness to see all patients without discrimination. This is great. The number of doctors and institutions that openly support the LGBTIQ community in Ukraine is growing even despite the war.

Five or seven years ago, when I started working in this area, it was almost impossible. Doctors who worked with LGBTIQ people were actually outcasts in their workplace. Now I regularly receive requests for training and express a desire to publicly support the community, including in Zaporizhzhia.

Unfortunately, these are only rare exceptions. I’ve had cases when mostly transgender people from frontline areas, in particular from the Kharkiv region and small villages, wrote to me. It is especially difficult when a person has chronic health problems. For example, I was approached by an LGBTIQ person with a disability who lived in a small town on the frontline, had mobility problems, but could not leave for a safer area due to lack of financial means.

These people need help, but often avoid going to the doctors, even in frontline areas. This problem existed even before the war. Many years ago, studies showed that LGBTIQ people often avoid medical facilities for fear of disclosure, condemnation or refusal of service. Unfortunately, cases of doctors refusing to treat transgender people, saying that “we need special doctors for people like you”, still happen today.

So the problem with medical care for LGBTIQ people is obvious, but we are trying to gradually work on it.

As for the temporarily occupied territories, I have not received any specific requests recently. However, the situation with LGBT+ people in Russia is very complicated in general. On the one hand, society condemns and is hostile to them, but before the full-scale invasion, at least there were medical facilities in Russia where transitioning could be carried out. Now the situation has become even more complicated, as those who adhere to civilised values have already left the country.

You mentioned that doctors in Zaporizhzhia and in Ukraine as a whole have started to come to you more often and say that they are friendly to LGBTIQ people and are ready to work with them. What do you think is the reason for this? Perhaps demand creates supply?

I always encourage LGBTIQ people to be visible if it is safe for them and to see doctors. Over the past year or two, the number of requests from doctors has increased significantly, especially for transgender people. Lesbians and gays are hardly ever written about, as they do not have specific medical requests, unless it is about reproductive technologies. But transgender people have started to come to me more often. Sometimes patients pass on my contacts to their doctors, and they write to me with a question: “We don’t know what to do. Please help us”.

And it’s cool, because there are doctors who could simply refuse to help or even kick the patient out, but those who come to me are looking for answers, which shows a certain basic empathy. Even if a doctor doesn’t know what to do, they still try to help. And this is enough to be friendly to LGBTIQ people.

Together with the NGO Medical Leaders, we have created an educational course that includes six short videos about transitioning. I often send them to doctors and answer additional questions. This is all possible thanks to the visibility of LGBT+ people. Those doctors who used to think they didn’t have such patients now see that this is not the case. Patients just didn’t always make coming out.

Now the requests have become more frequent. If it’s a whole medical institution, I’m ready to conduct training for the whole team so that I don’t have to explain it to each doctor individually. But a lot depends on the management of the institution. When I approached my superiors in 2017 and said that I would work with transgender people, they simply replied: “You will not do this here. Go work in another institution”.

Later, we won thanks to the cooperation with the Insight organisation, but it was not easy at first. I understand that even if an individual doctor is LGBT+ friendly, their superiors may not approve. Moreover, doctors can be fired from their jobs because they work with transgender people.

This is a big problem, and it is important to work with the administration and health departments to ensure that they issue appropriate orders and explanations that are in line with civilised values. So yes, the answer to your question is broader. But it is important that people are not afraid to go to the doctors.

If more people apply, more doctors will understand the relevance of the topic. This will lead to more doctors participating in trainings, and we will be able to organise more events. This is an interconnected process.

You also said that LGBTIQ people often avoid going to the doctor for fear of being exposed, especially in small towns and villages. How can this be changed? Is this a multilateral process that also involves certain changes at the state level?

We need to talk about it. Yes, this is a very multi-level process. Even before the full-scale invasion, when I was conducting trainings, it was clear that one doctor cannot solve all the problems. They can help people, but there are certain limitations. For example, if a transgender person comes to a family doctor with a cardiac problem and needs a cardiogram, they need to undress for it. The doctor may not know what to do in such a situation. It is important to refer not only to a good cardiologist, but also to a doctor who will not discriminate or disclose information.

This is the first level. But it is important that the person trusted us and came. And what if there are cases of discrimination in the institution? The administration must clearly state that it will take the patient’s side. This applies not only to transgender people, but also to people with HIV, tuberculosis, etc.

In my trainings, I always emphasise that a doctor who can work adequately with transgender people is able to help everyone else – patients with HIV, disabilities, etc. – just as effectively. Discrimination has a chain reaction: if you start with one group, you can end up discriminating against anyone – people with tattoos, piercings, blue hair, etc.

We should strive to ensure that there is no difference in the way we work with patients. This depends on the policy of the institution itself, as well as at the level of health departments. For example, after my story, Insight arranged a training session at the Kyiv City State Administration for heads of medical institutions. Although my managers did not attend the training, receiving an official invitation influenced their attitude.

The Ministry of Health and the National Health Service of Ukraine also play an important role. It is important that there are official documents in place to help transgender people receive medical care without discrimination. Currently, the Ministry of Health is busy with transplants and rehabilitation of the wounded, so new initiatives, such as transitioning or reproductive technologies for LGBTIQ couples, are postponed for an indefinite period.

I fully agree that if doctors can work with transgender people, they can work with everyone. When I see that some doctors speak negatively about visits, for example, to Roma settlements, I understand that the topic of working with LGBTIQ people can no longer be raised with them.

Absolutely. Unfortunately, today universities do not teach basic empathy and communication skills. This needs to be changed. We do not have a systematic approach to this in medical institutions. If students are lucky, they will have a teacher who will teach them to treat people as individuals, not as a set of symptoms. But now this is an extremely rare case.

This is still not taught at the university level, and most people who have not studied at medical universities do not understand this. There is a perception that a doctor just needs to know the symptoms. But we need to go there and teach this at the university level. It is very difficult to convince doctors who have been working for 10, 20, 30 years. If they themselves do not have inner empathy and have not come to understand the importance of human equality, it is difficult to change their vision. Although there are some doctors who understand this and have no problems with it, but they are few and far between.

Therefore, it is necessary to teach massively at the university stage, and these should be permanent compulsory courses. The first step is to at least allow activists, human rights defenders and doctors who work with the LGBTIQ community to enter universities. It is important for doctors to be explained by other doctors, because they will not listen exclusively to LGBTIQ activists. Doctors need arguments from their colleagues.

This is the only way we can talk about institutional change, because now it is only isolated cases. The trainings conducted by our organisations are attended by almost the same audience. As a result, out of 30 people, only one or two will continue to work with the LGBTIQ community. We need to take a broader approach to this problem.

In conclusion, I have the following reflection. In February 2022, the city I was living in at the time was occupied, and I couldn’t leave for some time. Later, when I discussed this experience with my LGBTIQ friends, we talked about how queer people in the occupied territories try to become as invisible as possible, as if to “disappear” into the crowd.

However, this can often be seen in the territories controlled by the Ukrainian government. Perhaps that is why we do not know many painful stories yet?

Yes, it is true. We just don’t hear these stories. Some people think that there are no LGBT+ people in Ukraine because they don’t hear their stories. But as soon as they hear negative or positive stories, for example, stories of LGBTIQ couples, they are outraged. They think that this did not exist before, and now it is just a fashion. In reality, though, people are just trying to live their lives, not hide in corners. They start talking about themselves.

LGBTIQ people have always been, are and will be at all times. If their stories are not heard, a society that is homophobic does not see this and believes that there is no problem. And when people start talking about themselves, society is outraged because of this openness.

This is a very difficult path. For example, I am an LGBTIQ person myself. For a long time, I was perceived as an ally because I was in a heterosexual relationship, even though I was bisexual. I was considered a heterosexual expert. Now I’m in a homosexual relationship with a woman and I continue to talk about it and blog about it, so I’m not personally affected by hate anymore. My age and status allow me to ignore it.

But it is important for young LGBTIQ people because they need visibility. I know what I’m talking about, and we have to continue to pave this way – as experts in various fields and as people who speak out.

Changes are already underway, although two different scenarios are possible after the war. On the one hand, we are moving towards the civilised world, and under pressure from the European Union, we are adopting new laws and regulations. On the other hand, amid the war and the rise of right-wing radical groups, there is a risk that society will become more conservative.

Therefore, it is important to keep talking about it. Otherwise, we risk a setback in human rights in general, and this applies not only to the medical sector, but also to the human rights sector and others.

Since the war, many countries have faced a historic radicalisation towards conservative “family values”, which in fact have nothing to do with real values. That is why it is so important to raise these topics now, despite the hate.

The material was created with the support of Gender Stream in cooperation with the Center for Disaster Philanthropy. The views expressed within the project do not necessarily reflect the views of these organisations.