“It’s 7-8 kilometres here”: school principal in Kherson region forced by occupiers to swim across Dnipro because he did not want to cooperate

Serhii (name changed for security reasons) worked as a school principal in a village in the Left Bank of Kherson region. At first, after the occupation, the Russian military only passed through their village in transit, so teachers continued to teach local children online. But in the autumn, the Russians wanted to establish their own curriculum and came to the principal demanding cooperation.

Serhii was first detained in October 2022, held for four days in a garage with other captives – members of the ATO, tortured and intimidated in various ways: from threats to cut off his fingers with a grinder to pressure on his wife and family. When, after several months, it finally became clear to the occupiers that the principal would not cooperate, he was ordered, under threat of execution, to cross the mined bank of the Dnipro and swim across the river to get to the de-occupied territory of Kherson region.

He shared his story with ZMINA about the pressure on teachers during the occupation and how he managed to survive and escape with his family.

The torture chamber was a garage

Serhii says that at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the Russians simply marched in columns through their village to the Zaporizhzhia direction.

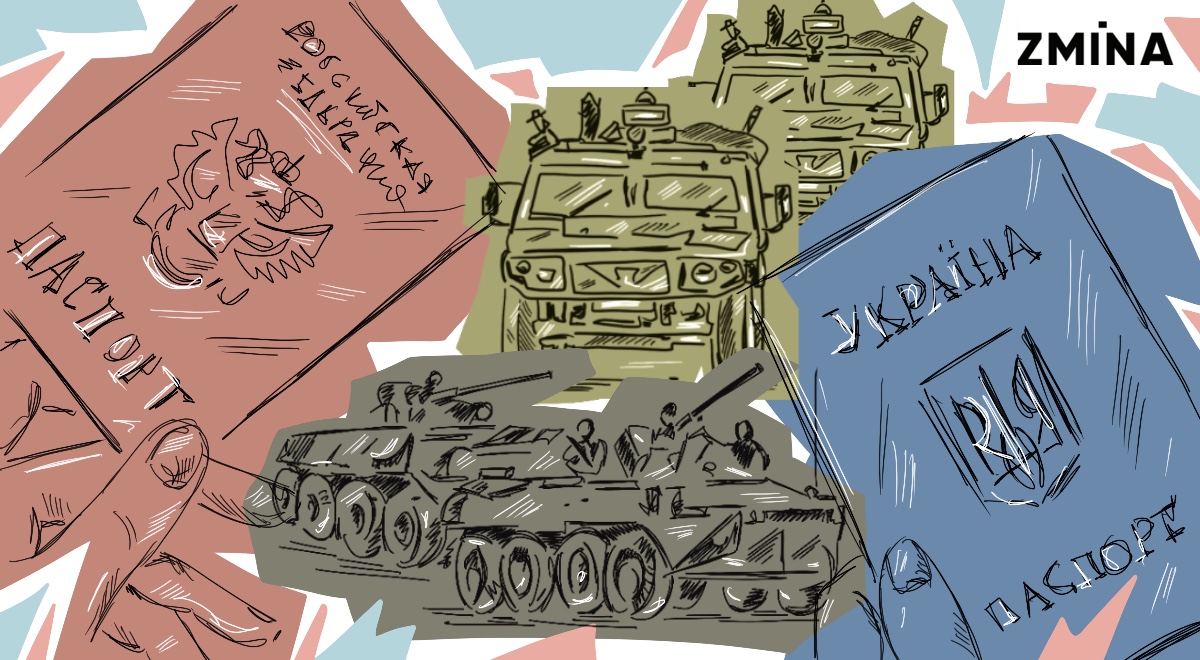

“Tanks, APCs, KAMAZs, MAZs, all military equipment. It was scary for us to see these columns. But they did not touch the local population”, the man recalls.

In the summer of 2022, the occupiers visited the village council several times. They needed some information at the time. They could also stop by to check documents, go shopping, and find out “who is doing what”. There was a headquarters of the Russian FSS in the neighbouring village, and they periodically went to the surrounding settlements.

The first time the Russians came to Serhii’s house was on October 30, 2022. Neighbours from the other side of the village had already called the family and told them that the occupiers had entered the village.

“We went outside. First of all, they checked our documents and phones, then came into the house with us. There were a lot of them, all with assault rifles. I don’t know how many of them there were, more than 20 people. There was a soldier every metre, an armoured personnel carrier and a Russian Patriot jeep near the yard”, says Serhii.

All cars passing their house on the road were also stopped and their documents checked.

The Russians started asking Serhii and his wife who they were and where they worked. Then they asked about their children.

“I also have an older son from my first marriage. He is a conscript and is currently serving. They started questioning me about where he serves, what he does. I said only that he was serving in Zakarpattia. They are not engaged in hostilities”, Serhii adds.

According to him, the Russians did not like the way he and his wife answered questions, so they were first taken to different rooms and then ordered to both get ready.

“We got dressed. We heard a lot of dirty words in our direction. They blindfolded us, tied our hands. They tied our fingers with ties, and pushed us both into an APC. And then they pulled me out of the APC and put me in a car patriot. They drove us around the village for a while”, the man recalls.

The couple was brought to school. But when the occupiers saw the Ukrainian flag, they immediately expressed their dissatisfaction with the fact that it had not yet been removed.

“Why didn’t you remove it? I said: “It didn’t bother me”, They forced me to remove it. They said: “Sing the Russian anthem”. I said: “I don’t know it”. “Repeat it after us”. So I did. And put the flag of Ukraine in my pocket”, adds the school principal.

Then Serhii and his wife were brought to the edge of the village, blindfolded, and their hands were tied. The woman was released because her son was alone at home. But he was left in the car. Two other ATO participants were taken from the village with him.

“When we were brought to the place, I was left in the garage, and the boys were taken to the kitchen. They were interrogated there until the evening, and I was interrogated in the garage. Physical violence… They threatened to cut off my toes with a grinder. They intimidated me. They asked me who was a patriot in our village, who was for Ukraine, who was not letting them work. Who else to take to intimidate more people”, Serhii says.

He says he was beaten, but gently, through a piece of cloth, so as not to leave marks. There were different people among the torturers: some just beat him, others came and spoke in a calm tone, asking him about something.

“I had to speak only Russian, because if you say a Ukrainian word, you will be hit so hard that you can’t breathe. I said it was hard for me to speak, I had never spoken Russian. They said: take your time and translate”, Serhii says.

He was tortured until the evening, and at 10 pm, one of the ATO members named Oleksandr (name changed for security reasons) was brought to his garage. The former soldier said that they were also beaten and that the second abducted ATO member, a young man, agreed to cooperate with the occupiers.

“When you have a rifle to your head, you will say anything, and when your family is being held hostage, the same thing. People will tell things about themselves that they have never done. In the morning, we saw that the guy was released, took him with us and went back to our village”, the school principal recalls.

In the morning, the prisoners were given water, but nothing to eat. In the evening of the second day, the Russians brought three more boys from their village to the torture chamber.

“Oleksandr and I were moved to the kitchen, and they were locked in the garage. The torture chamber was a garage. We heard them crying. They were young boys. One of them is my student, like our daughter (the couple has three children – Ed.), 19 years old”, Serhii says.

On the third day, at 12 am, a man who was the “elder” of this group of occupiers came to see Serhii. He said that the Russians had come to Serhii’s house and filmed his wife.

Serhii’s wife Oksana (name changed for security reasons) recalls that she saw an APC pull up to the house through the window that day. The Russians came into the yard and said they were there to shoot a video.

“I asked: “What video?” They say: “About how well you live in Russia”. What am I going to do against them? I started to tremble again… My husband is in a torture chamber, my child is at home… I asked: “What should I say?”. They answer: “Say that “thanks to the Russian Federation, we have a better life”… They gave me a flag”, the woman recalls.

When she asked about her husband, the Russians said that he was “not talkative”. “We can bring him without fingers”, the occupiers added.

They re-recorded the video several times to make it look “good”, and then gave Oksana the keys to the school, which they had taken from Serhii a few days earlier, and left.

“I was so disgusted at the time, and it was clear that everything they do is done at gunpoint. How can you say anything to them? You are defenceless”, she adds.

Starting from the new year, they wanted to teach children according to the Russian curriculum

Serhii recounts how the “elder” in the torture chamber showed him a video recorded by the occupiers with his wife:

“He said: “Your wife has realised everything. She is for Russia. Here, have a look”.

The Russian then added that if the man “cooperated”, everything would be fine. They might even feed him. Serhii asked for water instead:

“They gave me water. However, at about 12.30 they gave me another can of stew. I hadn’t eaten anything for two days before that”.

At night, another young man was brought to Serhii’s garage, and he recognised him as the school principal. Then the occupiers asked Serhii to have a “conversation” with the prisoner, “because he doesn’t know how to speak with Russian militaries”.

“It turns out that when they took him, they asked him who he would like to be. He is young, he is 19 years old. He answered: a soldier, like a brother. He was beaten badly”, the school principal recalls.

On the fourth day in the evening (November 3, 2022), the prisoners were released. They got their documents back, and some of them got their phones. They took them to a neighbouring village, and then Serhii called his neighbour to come and pick up the men.

On November 5, the occupants began to enter the village massively. They moved into empty houses. Russian soldiers also settled next door to Serhii’s family.

He recalls that after that, he and the entire teaching staff were not touched for almost six months. Teachers continued to teach local children online, and the principal distributed employment records and personal files to people so that they had everything “on hand” if anyone was going to leave.

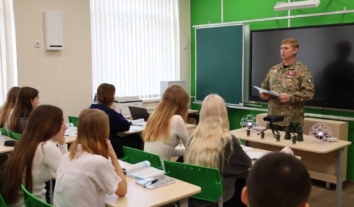

In August 2022, a school principal from a neighbouring village came to the village, who cooperated with the occupiers and introduced herself as the head of the occupation ‘education department’. She ordered the principal to gather the entire staff and urged them to cooperate with the Russians. At that time, she still addressed them in Ukrainian

“The catchphrase: “Who else but us will teach our children”. Only one of our team agreed to cooperate. She was not at the meeting, but she called back and said: “I’ll do it”, says Serhii.

The next time, according to Serhii, the new “head of the education department” arrived during the New Year period. She spoke Russian, and in addition to the teachers, she also gathered the children’s parents. They were offered to send their children to a school in the district centre, 30 kilometres away, where they were taught according to the Russian curriculum. But the parents said they wanted their children to study online this year, in Ukrainian.

“You will cross the Dnipro”

The second time the Russian military visited Serhii’s family was on June 21, 2023. The family had just finished pumping honey, and they were not expecting anyone to visit, as they were used to Russians walking down the street every day.

“I heard a knock at the gate. There were 11 people. They asked: “Where is your husband?”. I said: “In that yard”. I called Serhii”, Oksana recalls.

The Russians told the principal that they wanted to “talk” again, checked his phone and documents. They allowed the man to change his clothes and started asking him about his eldest son again.

“I said in the Zakarpattia region. He is in regular service. They do not conduct military operations. They didn’t believe me: “How can they not conduct hostilities? All conscripts are fighting. What unit?”. I said: “I don’t know, I don’t care. The main thing is that he is alive and healthy”, the man recalls.

He and his wife took out their Russian passports, saying that they had to change them because a colleague from a neighbouring village called and said that those who did not take a Russian passport would be given a month to leave, and then sent to the Krasnodar Krai. In addition, it was impossible to leave the village without Russian documents. So the family decided to take Russian passports. But they also kept their Ukrainian passports.

Oksana says that during the second search, the Russians took her computer and laptop. The occupiers persistently asked why the family would not leave the village if they did not want to cooperate.

“Why is the school in the neighbouring village open, but not yours? You are preventing us from working, you are betraying us. Why did you keep your Ukrainian passports?”, the woman retells the occupiers’ complaints.

After that, the Russians tore up Serhii and Oksana’s Ukrainian passports, which they found during the search. Then they told Serhii to take the keys, and the four Russians went with him to school.

On the way to school, one of them blamed Serhii again: “You don’t work yourself and you don’t let others work”.

“I did not forbid anyone to work”, Serhii replied.

Then they accused him of ordering his staff to cooperate with the occupation authorities.

The school principal recalls that he had drawn up the relevant documents for only two school employees – a teacher and a nurse. He adds that this is a common procedure: it is necessary to write an order for suspension from work, but with the preservation of the place of work until the end of hostilities without salary.

“The teacher signed the order without question. And another, a school nurse, went to work for the occupiers in a rural first-aid station. I asked her: “Are you officially employed, do you receive a salary?” She said yes. Then, I said, sign the order. She took a picture of the document. The people who came for me, they went to that rural first-aid station. So, maybe they took the phone from her, or she handed it over”, Serhii says.

The man adds that the nurse’s daughter, who worked in the local police, also cooperated with the occupiers, and her son worked in the military recruitment office, and he also began to cooperate with the occupation authorities.

Serhii was told that he had received a complaint, but was not told from whom.

“If he (the occupier – Ed.) retells me the content of that document, then he has seen it. And only one person could show it to him. The Russian added: “You don’t let others work in the same way, and people want to”, the man says.

When we arrived at the school, the principal opened all the doors except for the control room and the nurse’s office. When they went up to the second floor, to the computer room, the Russians asked where the equipment was. The man replied that the computers were old and had been written off before the war. But the occupiers did not believe him and promised to shoot him if he did not tell them where the equipment was. So Serhii told them where he had hidden the computers and printers.

After that, the Russians returned to his house with the man. They asked him again whether he was willing to cooperate with the occupation authorities, and when he refused, they ordered him to take a white sheet and go with them.

The man was put in a car with two men in the back seat and two more in the front. Serhii recognised the car because the Russians had taken it from local farmers. He tried to ask where he was being taken and for how long, and one of the occupants replied: “You will cross the Dnipro!”.

At that moment, Serhii realised that these were not the guys who had come for the first time, and that they were not taking him to the basement. By the way they were taking him, the man could tell that they were heading towards Dnipro. Somewhere in the middle of the road, one of the occupiers received a phone call.

“They said they had found computers, multimedia equipment and printers. They say that I can be imprisoned “for stealing state property”. I hear everything and think that Dnipro is better than prison. They took one of our boys – we still don’t know what happened to him or where he is… I think if it’s a prison, he has little chance of coming back”, says the school principal.

The Russian military took the man to a pier in one of the neighbouring villages. He recalls that there used to be a river port there. Everyone got out of the car, and the principal was forced to find a stick and tie a white sheet to it.

“Do you see that tower on the other side? It’s a mobile tower. You need to head there. It’s about 7-8 kilometres to cross this river. Good. You can go. Go to the de-occupied side… Step back – we shoot”, the man recalls.

When he took a few steps towards the Dnipro, one of the Russians shouted: “Look under your feet – there are mines there”, As it turned out, the entire bay was mined. According to the principal, the mines were arranged in six rows. The man did not immediately see the mines, but thanks to the occupier’s words, he realised that he had to be extremely careful and check every step, because it could be his last.

Serhii also later learned that the day after the occupiers forced him to walk along the mined bank, another civilian was brought to the same place, who did not reach the water and exploded on the mine.

But the school principal was lucky, and he made it to the water, threw away the stick and tied the sheet around himself.

“At first, I had to swim 700-800 metres against the current, and I was still hoping that somewhere, maybe, it would not be that deep. When I entered the water, I had already said goodbye to everyone. It was a shock. I feel that the current is very strong. I can feel my jacket and sheet pulling me… I think maybe it’s better: they will see that the jacket is being pulled by the current, so that means he is dead”, the man recalls.

He tried to swim against the current, but felt himself being carried away. Then Serhii began to swim towards the shore, but the strong current threw him away from the shore as well. Then the man tried to reach the bottom and realised that it would be easier for him to “walk” the bottom of the river. So he dived and walked along the bottom until he came back and reached the shore. Serhii knew he had to get back somehow, as his wife and child were at home, so he decided to move along the river in the hope of finding an unmined exit, as he had to reach a village (the name of the settlement is not mentioned for security reasons) and find a place to hide there before dark.

“I raised my head, looked out, and saw that the entire bank was covered in mines. There was a mine every 20 metres. It was impossible to get ashore. I crawled along the shore for a kilometre and a half, looked out from behind a hill: aha, I’m opposite the District Electrical Network, local orientation, so I’ve already moved away from them. I can see the dugouts there. They can see the mined area. They also watch from the garages where the locals keep their boats – there are cut-out windows”. Serhii says.

In some places, he could just duck and run, but there were places that were visible, and then he had to crawl. He said he remembered physical education lessons when he taught children to follow animal tracks.

“I crawled for maybe two kilometres, then got up a bit. I’m afraid of a big house on the bank. I think either they have already noticed and are watching where I’m going, or they have somehow not noticed me”, the man adds.

In one place, he saw a small path where animals were walking, so he decided to walk 50 metres along the dog tracks and eventually came to the shore. There he saw several unfinished Russian dugouts and “mine” signs, but he made it to the village. On the way, he met a Russian “gazelle”, from which he did not have time to hide, so he simply pretended to be drunk.

Leaving the occupation

“I decided to go to my friend’s house. I got to the yard, the gate was high, and I looked in: he was walking in the yard. As a joke, I shouted: “Do you have any feathers for sale?” He came out and said: “Serhii, what’s wrong with you? I answered: “Give me some water first, and then we’ll talk”, the man recalls.

A friend brought Serhii some water. They started talking, and then the friend suddenly said: “Wait. Let’s go to the garage and help”.

Already inside, he explained that people who support the occupiers live in the neighbourhood, so they had to be careful. Serhii could not stay at his friend’s place because it was dangerous for the owners themselves: Russian drones were constantly flying in the area, and his neighbours could have “handed him over” to the Russians. But he was allowed to wash, given a snack and a new set of clothes.

Serhii recalled that there was another friend of his in the village whom he had recently helped, so he decided to contact her:

“I had a hard time getting through to that yard. She came out. She asked: “Serhii, what’s wrong with you, what kind of clothes are you wearing? And I was given children’s clothes. It was clear that my shape and the shape of their children were slightly different. I said: “Let me hide somewhere, because it’s already seven o’clock in the evening, I can’t walk at night”.

The man told his friend what had happened to him. She called her son and asked him to see if the occupiers are there in the morning when he will be crossing the bridge.

“They have a car, and they bring goods to our village, they have a shop there. She said they had to transport a person, and didn’t explain anything on the phone. I said I needed to call home somehow to let them know I was alive. Then she called the shopkeeper in our village and said: “My godfather was supposed to come to see me, but your godfather came… I’m going to spend the night with your godfather. Tomorrow we will have a chance to talk”, the school principal said.

In the morning, the son of a friend came and said that there was no one on the bridge. Then Serhii decided to go to his aunt’s house, because he couldn’t stay at his friend’s house for long either.

He walked carefully because he knew he was known in the village. When he got to his aunt’s yard, he saw that Russian soldiers had moved into the house opposite.

“I walk in, and my uncle is standing in the yard. I asked if they were accepting guests. My uncle was happy. We went inside the house, and my aunt asked: “Did they let you go?”. “Yes, I said, they let me go. I told her about it, and she went numb. She didn’t know what to do with me. But I didn’t plan to stay with them”, the man says.

Then the relatives decided to settle Serhii with their nephew, because it seemed safer. The school principal stayed with his nephew for three days, and then the neighbours saw him and started asking questions: “Who is he and what is he doing here?”. As it turned out, they also supported the occupiers.

Then Serhii returned to his aunt and stayed with her for nine days.

During this time, his wife found carriers to leave together.

“I told him we had to leave, we were putting our families in danger. I found a carrier from Melitopol. I told him my story. I told him that we had no passports. He said: “Don’t worry, you can take a photocopy”. On July 30, a new bus came for us”, Oksana recalls.

She explained to the driver that she and her son were in one village, and her husband was in another. When the carrier was taking Oksana and her son away, the occupiers at the checkpoint started asking where they were going, and the driver told them that they were evacuating from the flooded areas to Melitopol. So they passed two checkpoints. Then they met with Serhii, and when they passed several more neighbouring settlements and realised that they were being let through at the checkpoints, they relaxed a bit.

Oksana recalls that when they arrived at the checkpoint in Novoazovsk, all the passengers on the bus showed their passports, but they did not have original documents, only copies.

“The Russian soldier called back somewhere, asked again, and said everything was fine. They gave us a form to fill out. There were nine of us, three Ukrainians… They started calling us one by one, one scanned our fingers, the other took photos, like a criminal. They asked questions about where I was going, where I came from”, Oksana recalls.

She and her husband said that they had left the flooded areas, but were nervous because if the occupiers had checked, they would have realised that their area was not flooded. After an hour and a half, they were given the documents, and they moved on. They travelled all night, arrived in Novoazovsk and then to Kolotylivka (they travelled through Russia).

“In Novoazovsk, they were not as rude as here. They hate us. They searched all our bags. All the documents. Only I was brought in for interrogation. My husband and son were not interrogated. They asked about the children, how old they were, whether they were serving”, Oksana said.

The Russians did let Serhii and his family through, but they had to walk 1,800 metres from Kolotylivka to Pokrovka in the Sumy region. On the Ukrainian territory, the military met the IDPs. Oksana says that buses were waiting for people, volunteers fed them for free and gave them the opportunity to spend the night. In the morning, buses also took people out for free.

The woman also said that the Ukrainian military checked their phones, and the family told them about what they had experienced during the occupation.

Then Serhii, his wife and son went to live with their two older daughters in Kyiv, where the family renewed their passports and got their lives back on track. But now they have been cut off from IDP payments and benefits for IDPs. Therefore, the family is still trying to resume payments from the state. Oksana has health problems and finds it difficult to work. And Serhii remains a school principal in the occupation, but remotely. He doesn’t want to leave his colleagues who are still in his native village. Therefore, it is also difficult for him to find a full-time job in Kyiv.

Serhii added that several children in his village are currently studying remotely at a Ukrainian school, and there are also those who were forced to go to school in a neighbouring village. Parents were threatened to take their children away if they did not agree. However, most of these children study at both Russian and Ukrainian schools at the same time: they agree to get in touch in the afternoon.