Judges, prosecutors and sperm producers: who “administers justice” in the occupied Luhansk region

Last year, the Russians focused on bringing the justice system in the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions to the federal level.

Earlier, ZMINA told how the monopoly of the “Donetsk” judges in the “supreme” and “regional courts” of the illegal “ Donetsk People’s Republic” has changed. We also wrote about who became judges in the occupied parts of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

Read about the work of the occupation courts in the Luhansk region in this article.

Collaborators at the helm

Unlike the “Supreme Court of the Donetsk People’s Republic,” the judicial system in the Luhansk region was brought up to the standards of the occupying country without radical changes. None of the major Russian influence groups have shown interest in this region.

Therefore, the appointments were made without intrigue – Svitlana Trifanova, a well-established separatist supporter, became the head of the Luhansk People’s Republic Supreme Court. In 2012, she was appointed by the Party of Regions to head the Luhansk District Administrative Court, and immediately after the occupation, she joined the “working group on lawmaking” of the so-called “People’s Council of the Luhansk People’s Republic.”

Since 2018, Trifonova has been heading the “Supreme Court of the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic” and appointed Roman Tverdokhlib, with whom she worked in the Ukrainian District Administrative Court and who now combines judicial work with teaching at the local “Ministry of Internal Affairs Academy,” as her deputy. In addition to the deputy, three other judges from Trifonova’s associates – Oksana Solonychenko, former deputy head of the court Olena Ostrovska, and Anton Lagutin – were selected as “judges” of the “Supreme Court” by the Russian selection procedure.

Other reliable personnel have also strengthened the position of the Luhansk People’s Republic in the court, which has already adopted Russian standards. Among them are Yevhen Reus, former minister of the “Council of Ministers of the Luhansk People’s Republic,” Lyubov Batyashova, member of the propaganda media “Ukrainian People’s Tribunal,” and Lyudmila Gedzoruk and Artem Poltavsky, military judges of the “Luhansk People’s Republic Military Court.” The latter, by the way, as deputy head of the “military court,” was directly involved in political persecution, in particular, the case of ‘treason’ against pro-Ukrainian Luhansk blogger Eduard Nedelyaev.

However, the infiltration of Russian judges into the “LPR Supreme Court” was not without its share of infiltrators. Five of the 30 Luhansk judges had previously worked in various Russian courts.

The most notable career is that of Alexei Bereza, who was promoted from the office of a peace judge in the Shakhtyn district of Rostov region to the position of a “judge” of the “Supreme Court” in Luhansk. His fellow countryman, Ihor Semtsiv, made a smoother career ascent from a position in the Shakhtyn City Court. Similarly, Tatiana Feskova, a judge from the peripheral town of Borodino in Krasnoyarsk Krai, and Elena Chudaykina from Tolyatti moved to Luhansk. Mordovian judge Lyudmila Kolchina completes this group. Before her appointment to the “Supreme Court of the Luhansk People’s Republic,” she was the deputy chairman of the Chamzinsky District Court and is known for not having delivered a single acquittal during her entire tenure.

Lyudmila Kolchina

Lyudmila KolchinaRelatives and security forces

The same tendency is observed in appointments at the district and city “courts” level of general jurisdiction in the “Luhansk People’s Republic.” Most leadership and judicial positions were assigned to people who had previously administered “justice in the name of the Luhansk People’s Republic” in these courts. In some cases, even such characters as the “judge” of Luhansk’s Oktyabrsky Court, Yulia Makarova, whose father and husband have criminal records, and whose father and stepfather had criminal records in Soviet times, were selected.

Yulia Makarova

Yulia MakarovaIt is worth noting that the local “judiciary” was formed, in particular, based on family and clan relations.

For example, Oleksandr Semendyaev, a “judge” of the Zhovtnevyi Court of Luhansk, who previously worked as a chief specialist in the legal support department of the “State Committee of Taxes and Fees of the Luhansk People’s Republic,” is the son of Inessa Semendyaeva, an “honored lawyer of the Luhansk People’s Republic” and a judge of the District Administrative Court and then the “Supreme Court of the Luhansk People’s Republic.” The Pampur couple staffs two district “courts” in Luhansk, and Oleksandr Gorenko, who is most likely the son of the murdered “Luhansk People’s Republic Prosecutor General” Serhiy Gorenko, was appointed head of the Bilovodsk District Court.

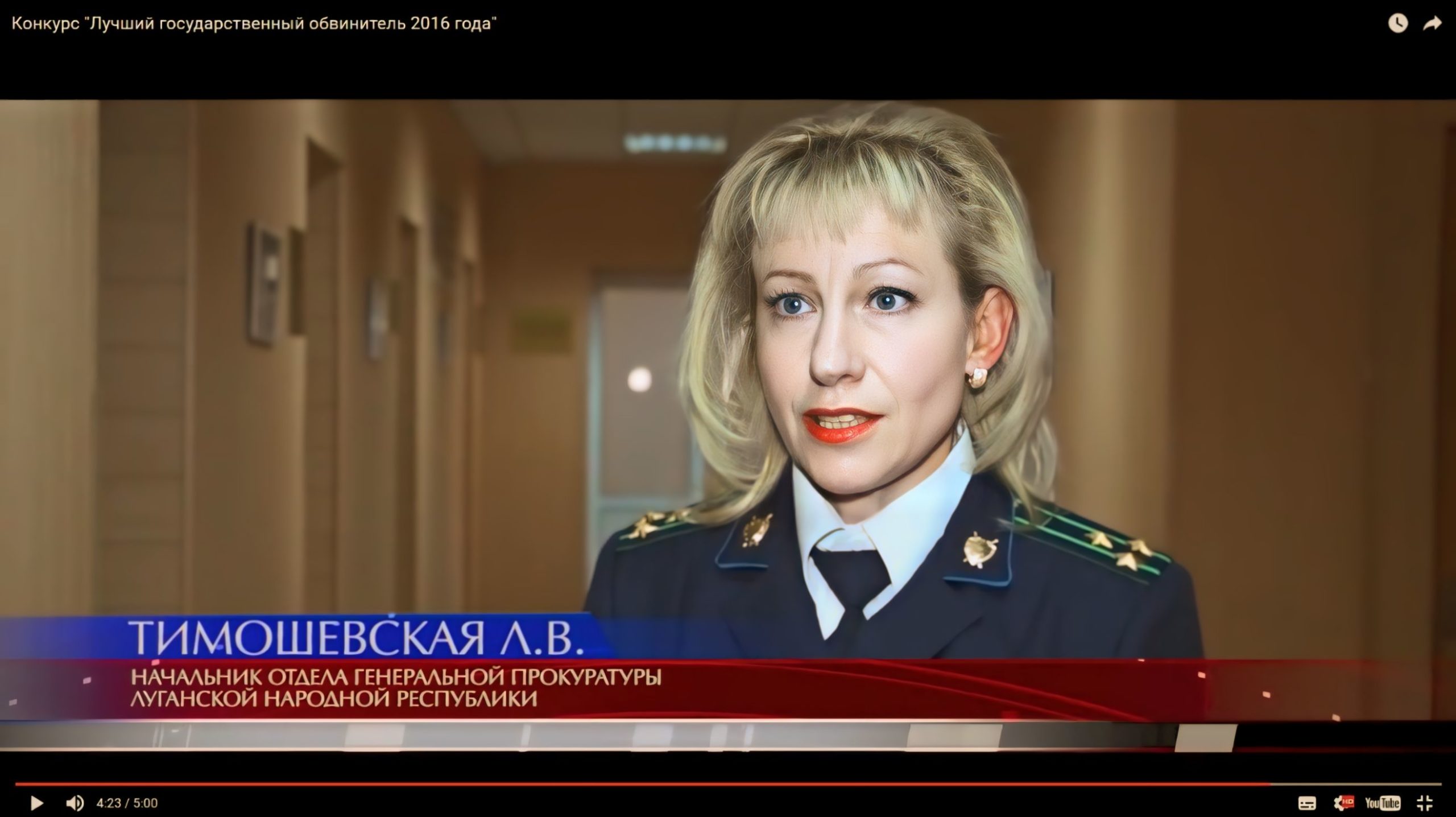

Local security forces became the critical donor for the renewed “judiciary” of general jurisdiction. For example, Roman Shulga, a retired Interior Ministry official who had previously headed the city police department in Krasnyi Luch, was immediately appointed head of the Markivskyi District Court. Larysa Tymoshevska, a participant in the contest for “Best Public Prosecutor of 2016” from the “Luhansk People’s Republic General Prosecutor’s Office,” became the head of the “Artemivsk Court” in Luhansk.

Larysa Tymoshevska

Larysa TymoshevskaHalf of the “judges” in this institution, such as Ihor Holokha and Mykyta Mazurak, worked in the prosecutor’s office until recently. A “judge” of the same court, Olena Markovska, was a senior assistant to the head of the investigation department of the “investigative committee.”

Ihor Holokha

Ihor Holokha Olena Markovska

Olena MarkovskaHowever, there are other interesting career stories. For example, Ali Tagiev, previously an assistant judge in the “Supreme Court of the LPR,” became the head of the “Stanychno-Luhansk District Court.” Roman Pylypey, the full namesake of the former director of the Spetsavtomatika Institute, a company that produces automatic fire extinguishing systems, was appointed to the Leninsky District Court of Luhansk.

Shortages at the frontline

The number of judicial officers “imported” from the Russian hinterland is extremely low compared to other occupied regions. Out of 109 identified servants of Themis in the “courts” of general jurisdiction of the “LPR,” only seven Russians were found.

In all cases, they have been appointed to positions with higher status—five of the seven Russian figures previously worked in magistrate courts in the Volgograd and Rostov regions, as well as in Omsk City and the Omsk region. Due to the small representation, it is not yet possible to talk about any regional groups of influence.

At the same time, some appointments indicate an acute shortage of “judges” in the frontline regions. It is likely that the “young republic” is ready to hire people who have no experience as judges. For example, a Krasnodar lawyer, Ivan Gukasov, was appointed to the “Lysychansk City Court,” and a current Ukrainian lawyer, Dmytro Akinshyn, is likely to be appointed as the head of the “Svatove District Court.” ZMINA sent a request to Akinshyn’s e-mail address indicated in the registration documents to confirm or deny that he had received the status of a Russian judge but received no response.

Also, due to the complete lack of public information about the past of this “judge,” it is impossible to confirm or deny a spicy detail from the life of a certain person who has a complete match of surname, name, and patronymic with a Ukrainian lawyer and “judge” from Svatovo, Luhansk region. The fact is that until recently, in the city of Shakhty, Rostov Region, LLC Management Company Greenwich was registered, half of which was owned by Dmitry Vasilyevich Akinshin, the full namesake of the current judge. The activities of this company include trade and “sperm production.”

At the same time, it should be noted that, apart from these two mysterious characters, no other judges willing to administer justice near the contact line have been identified. For example, nothing is known about the appointment of judges in Kreminna, Pervomaiske, Rubizhne, and Severodonetsk. Such institutions are not listed in the registers of Russian legal entities, and the addresses of these courts are listed in other settlements of the occupied Luhansk region in the State Administration of Justice system.