I sewed up vaginal tears with veterinary needle and capron for sails: Story of gynecologist from Izyum

I’ve been working as a doctor in the Izyum Maternity Hospital all my life. During the occupation, I was the only one of the eleven gynecologists in the town. Another female doctor, who did not leave, was killed during the aerial bombardment of a five-story building on Pershotravneva Street in early March. In April, a Russian with a call sign “Sherkhan”, I think he is a FSB agent, was instructed to create “some kind of medicine” on our bank of the town. Then I was called to work at the clinic. I didn’t want to go but I couldn’t refuse. I understood that I was the only one, and people needed help.

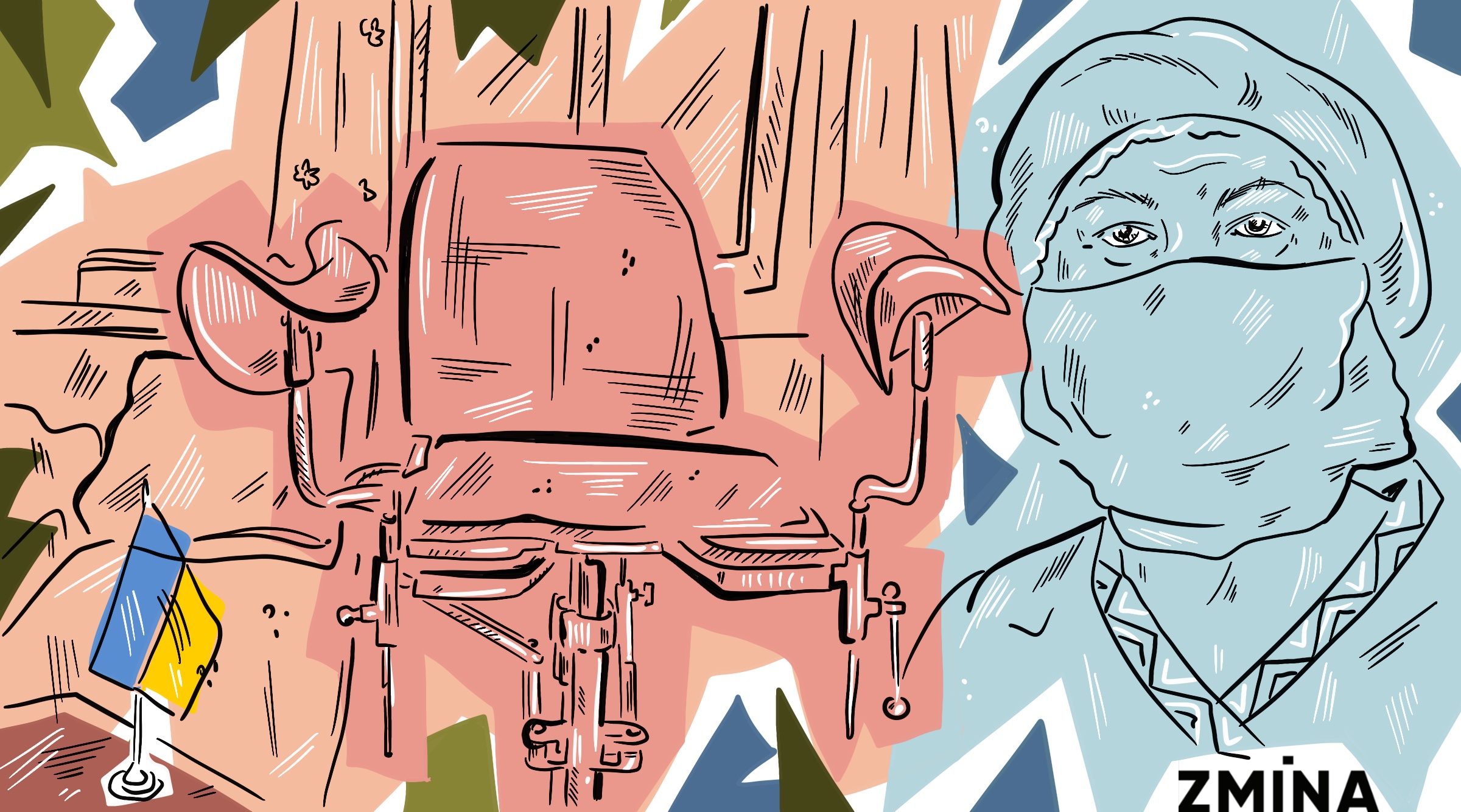

Illustration author: Tetiana Hushchyna

Illustration author: Tetiana HushchynaIn fact, I was a dispatcher: I kept records of pregnant women and sent women for scheduled deliveries to then-occupied Kupyansk. However, many of them were not registered or could not get there. I delivered babies twice at home without electricity. In March, Ukrainian volunteers found a gynecological chair for me somewhere. It is in my husband’s study. The Russian military did not provide me with any equipment.

It was horrible. I was very nervous, I had an enormous responsibility. If there were any complications during childbirth, I could not do anything. I only could deliver an uneventful baby. I just could sew up vaginal tears with a veterinary needle. We have a yacht, my husband sewed the sails himself, there was capron thread left. I soaked it in alcohol and sewed tears up.

I had to stop hemorrhages if there was no time left to take a woman in labor to a hospital. There were situations when a woman would have died if I had not helped. I’m not bragging, believe me. Under normal conditions, what I had to deal with was elementary work for a gynecologist.

I also had to deliver a baby in a Russian military hospital. A woman was brought to them. She was taken wherever she could be taken. The military holding assault rifles came after me and took me away in an armored personnel carrier.

It was difficult to endure the occupiers’ pressure. One day I was severely depressed, I hadn’t seen my children and grandchildren for a long time. “Sherkhan” came to my office, he was very cheerful.

“How are you?” he asks me.

“I’m bad, because Izyum is like a prison,” I answer.

I couldn’t stand it. They did not let us go to [government-controlled] Ukraine. Women and children could leave through Pechenihy. But there it was necessary to walk along the embankment for a long time, which I physically could not do – I have knee arthrosis. Moreover, our car was hit by debris. We were also afraid to go because of looting. When I lost my nerve sometimes, I told my husband: “Let’s get out of here.” He didn’t want to. He has a good workshop, he likes to design. He did not want to give away what he had collected and built for decades. At our age, it is difficult to be left with nothing and to build a new life.

I never wanted to go to Russia. I told “Sherkhan” during that conversation that I planned to go to Italy. And he said to me: “Why do you need that Italy? This is an unfriendly country, we have Dagestan and Altai… Is there something you are not satisfied with?” I answered him: “Yes, it is.” I said that I wanted to live in a free country. Although we have problems in Ukraine, we should admit that, we have freedom.

When I told “Sherkhan” that Stepan Bandera is our national hero, he ran out at breakneck speed. Then I thought that the FSB would come after me. I also wore an embroidered dress to work and I kept a Ukrainian flag on my desk.

I believe that my age saved me, I am not young, and the fact that I was the only gynecologist in the town. The deputy mayor [Hlib Tkachenko, installed by the occupiers] asked people to tell me not to “talk a lot”, as I have always supported Ukraine and never hid it, otherwise he would “pull my legs out”.

They came to search my house. But they did not go inside, only looked around the yard. After the liberation, the Ukrainian military also searched my cellar. Having found a Russian canned stew, they asked me: “Well, what is it?” I explained calmly to them that we had to eat something. The occupiers did not pay money, giving food rations instead.

Illustration author: Tetiana Hushchyna

Illustration author: Tetiana HushchynaIt was not so much the Russian military who looted the town but the so-called “LPR military”: all the cellars were cleaned out. And while leaving the town, the Russians grabbed satellite dishes and many cars. Although they boast of Russia, I see that they have lower living standards.

The military was stationed in Verkhnie village and they frequently “mopped up” local houses. Russians came in and were astonished: “Oh, you have a bath.” They settled in empty houses. They visited our dentist in crowds as if no one had ever treated their teeth. There were many Buryats, Dagestanis, men from Siberia.

We tried not to cross paths with the Russian military but we had to talk to “LPR military” at checkpoints. They complained that they were fed up, that they wanted to go home to their children. I asked one of them why they came here. He was delivered to our clinic with high blood pressure, and I wondered how he passed the medical examination with such health condition. He answered: “What are you talking about, they took me right out of a coal mine.”

We saw that the Russian military had better equipment. The uniform of “LPR military” was terrible. The faces of the first ones who arrived had at least some signs of intelligence. After the rotation, many elderly people were brought. The faces of some, I say as a doctor, showed signs of mental retardation.

Illustration author: Tetiana Hushchyna

Illustration author: Tetiana HushchynaI believe that Russia must compensate me for moral and material damages.

But I don’t know how to evaluate these six months. During the day, you are somehow still busy with work, water, firewood. And there was terrible shelling at night. We were afraid to go to sleep. It was hell here.

Many injured civilians were delivered to our clinic, especially when the town was shelled with cluster munitions. However, an ambulance did not work around the clock. There was a case when ambulance drivers spent the night in a commandant’s office because they violated the curfew.

There was no electricity in Izyum for three months. It appeared in mid-May but was not stable: sometimes we had electricity for two days, then it was cut off again. Shelling was constant. Local men twisted the wires themselves, and Enerhozbut electricity company connected them.

In March, we lived in a complete information vacuum. We had an old radio. At first, it “caught” both Ukraine and Russia. Then Ukrainian signals were jammed. We tried to learn at least something from the Russian news reports, although we understood that they were distorted. Now the radio also mainly catches Russian stations, but we can listen to Ukrainian news after 20:00.

We were gathering information in fragments. An ambulance driver had a good radio in his car, he was telling me what he heard. He once joked about me:

“Olha Ivanivna, they will take you to the basement.”

I have been a Ukrainian nationalist all my life, one might say. Although I speak Russian.

It’s probably because of my dad. When my parents talked about the war, my mother talked about how people ran and shouted: “For Motherland! For Stalin!” And my father told me about anti-retreat forces and gave Solzhenitsyn books to read.

My husband and I are from the east, but my soul is in Zakarpattia [western Ukraine]. I read history books and I always feel so sorry for our Ukraine because everyone is tearing us apart.

Some foreign journalists asked me:

“What are you afraid of more: occupation or shelling?“

Occupation. I am afraid, I am very afraid of their return. Journalists were also interested in my attitude toward Russians. I didn’t like them before the war, but now I hate them.

Recorded by ZMINA journalist Yelyzaveta Sokurenko